Your Mother Imagines a Thousand Lives for You

Things Go Wrong

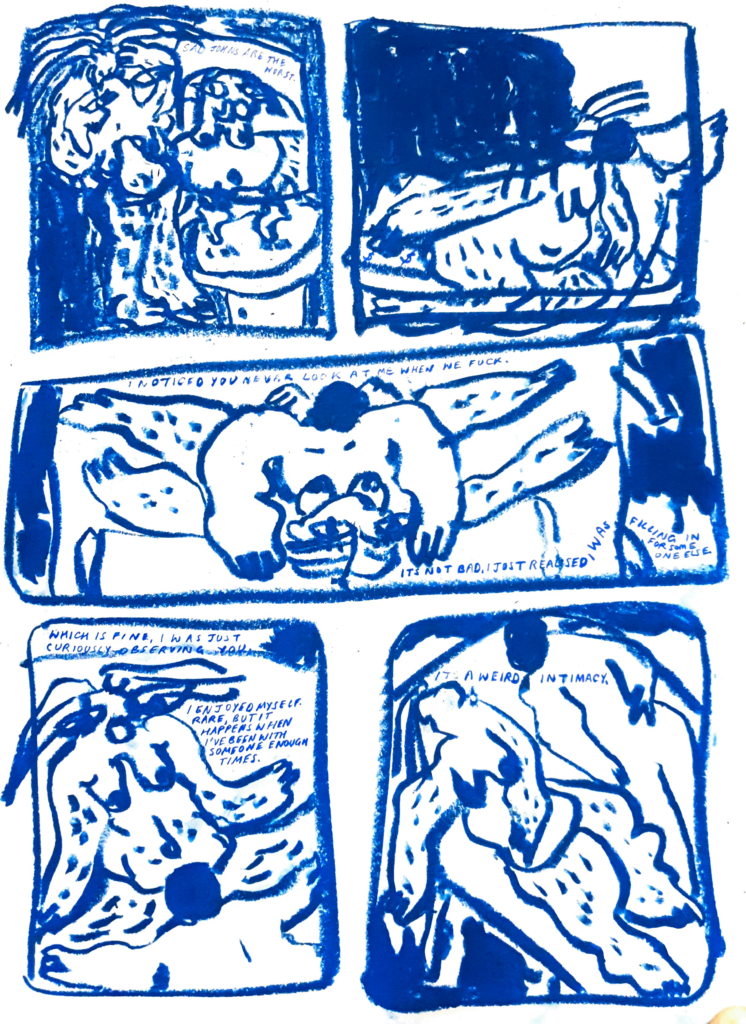

Last week little melons of ice came down hard for fifteen minutes. The worst hail you’ve seen in all the fifteen years that you’ve lived in Virginia. It put holes in your roof that was already overdue to be replaced. Jeff lost his job in February and y’all are tight on money. It’s not just about the job but he’s been having a hard time finishing lately. Your sex has become like a deer you see in the park. You approach it quietly with your hand outstretched. You tell it with your eyes that it can trust you. You are getting closer and you wonder if it’ll really let you near and then it runs off. Jeff is embarrassed all the time. Every time you try to encourage him it makes things terrible. He moves rapidly in you for a few minutes and then pulls out completely soft. You scratch his back lightly while he sits on the edge of the bed and you say something about it being fine. He says he’s just so tired all the time.

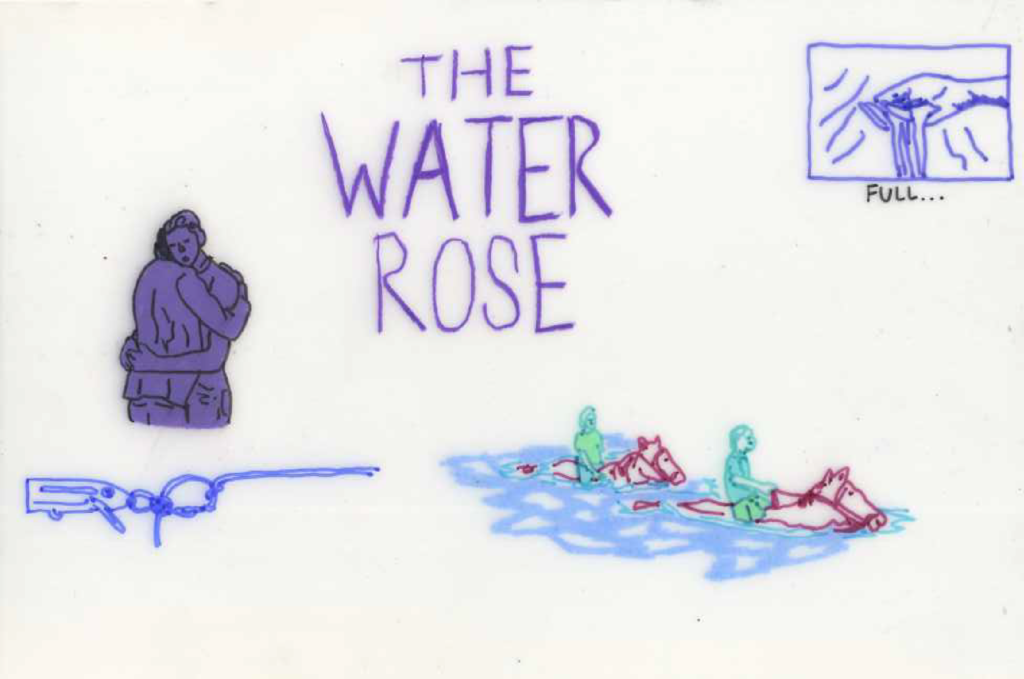

On the night it hails you both watch with the door open. You hear it damaging the roof. Watermarks form on the ceiling. The kids run around announcing new leaks as you run out of dishes big enough to hold the water if it lasts through the night. You hear Jeff slam the door to your bedroom and yell, “Fuck!” When it stops, the kids go outside and they keep shouting that they found an even bigger one while they hold the hail in their hands like crystal balls. There’s excitement in their voices. You wish for once they could shut up and understand how unexciting weather is and how horrible and boring the world feels to grown-ups like you.

The roof costs you a few thousand you don’t have, and you and Jeff get in a fight about the grocery bill for this week. It’s your daughter’s birthday next week and you go onto Facebook Marketplace to see if you can find a single thing that would be nice for her. It’s your family computer that you’re on and it’s Jeff’s Facebook page that is still logged in. He has a new message from a name you don’t know. You open the message. It’s from someone that refers to Jeff as “daddy” in every comment. Your stomach fills with concrete. You go to the top of the messages. They go back for months. The beginning and really all throughout are Jeff confirming that this person is only eleven years old and how hard that makes him. He’s promised her money for pictures a few times. They aren’t on here. They’ve worked out a more private way of exchanging those files. You scream Jeff’s name. He isn’t home. You start to shiver the way you do when you’re upset. You hear the window break. A little ice melon sits on your floor like a wad of heaven’s dip spit. All this time you didn’t even hear that it had started raining. The children run inside. They yell that the hail is even bigger this time. You hear it making holes in the new roof.

You are ugly. Your eyes are small and your nose is like a witch’s. You don’t have lips really. Your mouth looks like it was cut into your face last minute before they sent you down the chute. Your hair is thick at the root and thin on the ends. It is always oily. Your penis is incredibly small. You get your first boner in math class and it doesn’t raise the tent on your denim crotch at all. Worst of all is your acne. Which is cystic and blooms over your face leaving no place untouched by volcanoes both dormant and erupting every day.

You’re so ugly that the children don’t tease you. They are unkind to their friends and you are no one’s friend. When everyone gathers in the auditorium and the woman in the long skirt talks about how her son killed himself after being bullied, everyone in your grade promises themselves to stop talking about how ugly you are at their own parties and saying, “What! It’s the truth!” Instead they’ll be the person who says, “Guys, stop. That’s mean.” Some of the girls will resolve to let you join them when the teacher says the class has earned choosing their own reading discovery groups this week. They will say, “You can be in our group if you don’t have one yet.”

Each interaction with the children at your school feels like it will make you explode. They all feel like interviews for if you can go to the next level of being alive. The girls in your reading discovery group ask you first what role you want to be first and you say you’ll be the note-catcher. Kiera, the most beautiful person you’ve ever seen in the sixth grade, huffs and folds her arms. Emilia explains that usually Kiera likes to be note-catcher because she has good handwriting. You got this interview question wrong. You’ll stay at this level of living forever. You say of course Kiera can be whatever she wants. But you stutter as you say it. You are so bad at charm. No one ever talks to you and you can never practice these little banters and impressions and exchanges that the other children are so good at. You are the group’s page-finder. It’s an impossible job. You doubt Ms. Lions could even do this well. When the girls say parts that they remember as using imagery from chapters two through six of The Giver you’re supposed to leaf through those fifty-four pages and somehow land on what they’re talking about. You find an example on page forty-six and ask Emilia if it’s the quote she wanted to use. She says, “No, I meant another part.” You feel so sweaty. You touch your cheek and your fingers come away with a little spot of blood. One of your pimples is bleeding which is regular but still terrible. You wipe your hand on your pants and look up to see the girls watching you like an animal in a cage. An animal they feel bad for but also an animal they hate.

Lorenzo comes in late to class. He was at the dentist this morning. Ms. Lions says to join a reading discovery group. He approaches your group and all the girls start to smile and smirk and roll their eyes. Lorenzo starts to take off his backpack but Ms. Lions tells him that your group already has four people and to join a three-person group. The girls have neutral faces. They know if they pout you will know they’re upset with you. Their faces are stone but their eyes glaze over and focus on corners of the floor. They are wondering why being a good person inevitably makes your life worse. They could have been a three-person group. Your blood would not be on the group’s copy of The Giver. They could have finished early and talked to Lorenzo about the new color of his braces. This could have been fun but because of you it’s not. You will learn to evaluate every human interaction this way. You will always think about how people are thinking about you. One day someone will really need your help. You’ll realize you have no capabilities to think about what they need, only what they think about you. All this time your ugliness has been making its way to your core.

It’s your twenty-fifth birthday and you spend it alone. Loneliness is the zeitgeist of your generation so you feel a little comforted about how sad you feel. This is what birthdays are like for adults. Lots of young, successful, medium-beautiful, medium-interesting women spend birthdays alone. It’s really okay, you think. You go to bed.

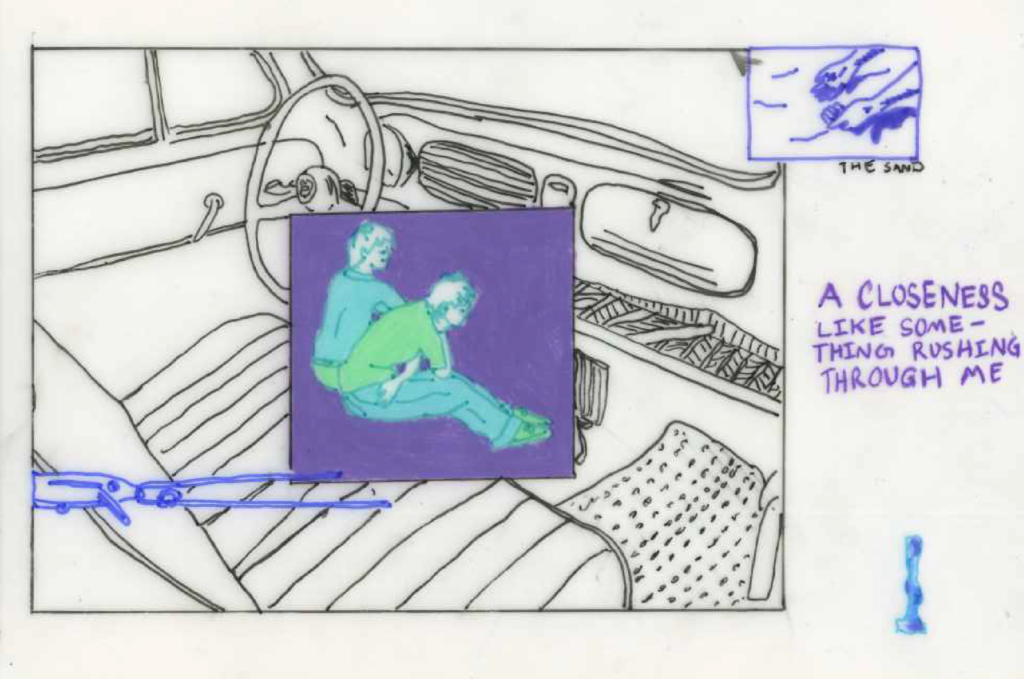

Tonight you have a sex dream about Gary Cole. He is the actor who plays Kent Davidson on HBO’s hit show VEEP. In the dream you’re in an attic with Gary Cole. He’s inside you and on top of you and holding your head. There is light from a lantern in the attic and there’s some kind of storm outside. Like a tornado. There’s lots of other people in the attic and Gary Cole is shouting directions to them for what to do about the storm. While he’s yelling at them he’s stroking the hair behind your ear. Everyone else leaves and Gary Cole starts thrusting inside of you. He kisses your mouth deeply with one hand still cradling your head and the other grabbing the side of your hip with his thumb on your hip bone and his other fingers pressing into your love handle. It feels really good but it’s a dream and you won’t actually have an orgasm. Every so often someone comes in with a question about the storm and Gary answers them and sends them away while not stopping the motion of his hips. He moves his hands to your boobs when these little gofers leave and kisses you again.

You wake up in love with Gary Cole. You look at pictures of him on Google Images and look at his IMDb. He’s in so many things! You had forgotten that he played the army sergeant stepfather in the Hilary Duff Disney Channel Original Movie, Cadet Kelly. When you had watched that movie at thirteen years old, you had rooted for Hilary to get with the young boy that was teaching her saber drills. You didn’t know then what a forceful yet tender lover Gary Cole was. If you did know then, you would have wanted Hilary to complete her time at military boarding school, grow up and go off to college, come home her senior year when her mom suddenly dies after getting hit by a car, go into Gary Cole’s office where he sits alone in his military uniform drinking whiskey and say, “I’m sorry, stepdad,” and then he’d say, “I’m sorry too that your mom is dead, Cadet Kelly.” He’d reach for the back of her head and say, “Is there anything I can do?” and then Hilary would touch his cheek and say, “Yes.” She would lean in close and kiss him. He’d keep his eyes open at first, unsure if he should let the moment happen. But then he would give into it and hoist her by her waist onto his military desk. He would reach down her pants and stick his middle finger in her. He would pull it out slowly and use the wetness on his finger to rub her clit. Then he’d reenter her with two fingers this time and Hilary would moan loudly. You start to wonder how you can get in touch with Gary Cole.

You’ve never felt this way before. You always thought it was so silly when people fell in love with celebrities. Even as a teenager when your friends fell in love with the Jonas Brothers, you didn’t understand how they could be so illogical. Of course they’d never meet them. When one of their dads pulled all his strings at Verizon headquarters to get her backstage passes to a Jonas Brothers concert, and she flaunted them for a whole week, you couldn’t help but feel sorry for her. Didn’t she know that even a face-to-face interaction didn’t guarantee anything? You and your friends were not the kind of girls people fell in love with in a moment. The Jonas Brothers would take a picture with her and never talk to her again. You had wondered why your friend was being so pathetic to love someone who would never love her back in this lifetime. But here you are experiencing love for the first time in your life and it’s with Gary Cole, an actor, a person very far away. What will you do? Move to California? Get a new job? Stalk his home? Even if you could orchestrate a seemingly random encounter, he would not fall in love with you. You will never meet Gary Cole. You will never have anywhere to put this love and no one will ever hold your head.

You and your boyfriend go to a park to do some kissing. Someone murders the both of you. It makes the park safe for everyone forever. They will snuggle up to their friends in tents and say, “Guys, I think I hear something. It’s that murderer who killed those people who came here to do some kissing.” But they’ll know they are safe. How many times can an odd thing happen in the same place, really? You were the ones who got murdered so it won’t be them and their friends. When the murderer is stabbing your boyfriend and you are screaming, this thought runs across your mind. You think, “Oh no, I’m the person this is happening to.”

Your dog wakes you up by licking your hand. You pull back a curtain and step around your dad’s bed to get to the door. You step on a half-used ketchup packet while putting on Mitsi’s leash. You whisper, “Damnit.” Your dad wakes up and sees you wiping it off with a plastic bag you found on the floor. He says his sorry. You say it’s fine, you slip on your snow boots and jacket and you take Mitsi outside.

Mitsi loves the snow. She keeps staring at it and jumping out of it suddenly like it’s surprising her. You unlock her leash from its short setting and let her run around you like a tether ball. You check your phone while she plays. You have three hours until the interview. You check your email and your Instagram and every few seconds you look back up to the top of your phone to see the time. You have to make sure it doesn’t suddenly become the hour of the interview without you knowing it. Mitsi tugs at her leash and you inch forward a little to let her explore. She’s sniffing around the gutter of the street and picks something up in her mouth. You tell her to drop it but she runs back to you with a bird in her mouth. You have to run away from her because the legs and the feathers scare you so much. She thinks it’s a game. You run away from her while also taking her with you because she’s on a leash. You dodge her and drag her for five minutes before she drops the bird. There is snow on her little wiry beard and her fur is pushed up a little so she looks like she’s smiling. It’s clear to you she’s the best thing about your life. In a few hours she’ll be dead.

You sign into the virtual interview and set up your screen so there aren’t any meds or trash bags in it. You have a blazer on and your notecards in your lap. You listen to the instructions for the interview—two-minute recorded responses to each question, no do-overs—when Mitsi starts to bark. The video instructions tell you that you’ll have ten seconds to consider your response before the timer starts. There are four questions total. Mitsi is still barking when the first question flashes on the screen. You use your ten seconds to beg your dad to take her outside. He says okay. His tremor makes it difficult for him to pick up the leash that you, thank heavens, left attached to the collar. You’re forty-five seconds into your first response before they’re out the door. Mitsi was barking the whole time. You feel as though you’ve already lost the interview. It’s a wide applicant pool and so many others won’t have a dog barking through the whole response, won’t have darting eyes to the door to see if their dad is managing alright. You get through the second and third response fine. Maybe better than fine. You referenced an article you’d read about research in the second one which felt like an intelligent thing to say. Maybe something other applicants wouldn’t do.

In the ten-second contemplation time before the last response, you see your dad’s tremor get severe. Mitsi sees something, maybe the dead bird from earlier, and darts at it. Your dad drops the leash and falls over. Mitsi runs fast into the busy street. A car hits her immediately and her body flies into the middle of the street. The car doesn’t stop. Another car hits her again. This car does stop. There are two of you in this moment. There is your body that stays behind to answer the question. Your mouth keeps saying sentences about how you’d react in a hypothetical situation with a prospective client. The other you floats like a ghost over your dad who still hasn’t gotten up and over the stranger holding your dog’s body. Mitsi is clearly dead. You’re surprised the stranger would even pick her up. There is so much blood. Her head looks to be crushed in. Still you wonder if she’s a little bit alive, just alive enough to see your face one more time. Maybe she has one eyeball still intact to see you smile at her or something. She’s not. She’s super dead. The stranger brings Mitsi past the guardrail into the apartment building’s parking lot but quickly puts her down to help your dad. They call 911. Your interview is over. You watched someone else hold your dog as she died so you could answer a question for a job you won’t get.

There is a betrayal on the spaceship. Your best friend, your co-pilot, cuts you loose while you do maintenance work outside. You start drifting away and you don’t have control over your body. You become disoriented. In your final moments you feel a great panic that dying in space means you don’t even have the comfort of direction. Your body will move eternally in some way that no one knows. You could forever be going what was once to you, down.

You take a vow of silence but you can’t get this one song out of your head.

You are a ghost but not one ever moves into the house you haunt.

Things Go Well

The note from your aunt’s will and testament says, “Cupcake, the house is yours. Sell it if you want. If you keep it, don’t try to sell the tea in the sink. No one wants it, I tried. Maybe ask your sister to come stay with you. What do I know? I’m dead.” You move in the next week. The house has a garden out back with flowers and fruits. Each room is painted a different color but it doesn’t overwhelm you. It’s like your aunt sat in each room and meditated for many days about how light came in and chose the right color accordingly. There’s a wonderful library with a large chair that has an afghan thrown over the back and a little stool for your feet. There’s a fireplace in both bedrooms and a window that you can see a little bit of the bay from. The kitchen has basil and rosemary set up on the windowsill and copper pots and sharp knives.

Down in the basement where the laundry machine is, there’s a porcelain sink under a single spigot coming out from the stone wall. You put your delicates in the sink to wash and when you turn the knob a dark liquid comes out. Luckily it only splashed on your black lace thongs. You think for a moment it must be rust but it fills the room with a sweet smell. You realize this is the tea in the sink from your aunt’s note. It always comes out hot.

After a few weeks of living there, you find a job. It doesn’t have the prestige of the one you were fired from before you moved but you feel completely happy in that you know what to do each day. You know when to go in, what to do while you’re there, and when to leave. You realize that you are living the good life. But you are alone. You call your sister. You say, “Let’s stop being mad at each other.” She agrees to come for a visit. She’s bitter your aunt left the house to you. You tell her you’d share it with her. You tell her both bedrooms have fireplaces. Only one has a view of the bay but the other gets the best light in the house. You tell her she can pick. You tell her about the endless tea available to you in the basement. You ask her, wouldn’t it be nice to come home from work each day and have a small tea party? You say, “Please?” She says okay.

A year passes and you and your sister settle into routines. She vacuums and you dust. You make breakfast and she makes dinner. You work at different places but each evening you come home and put on a lounge dress and sunglasses and a little lipstick and go to the back patio facing the garden and have your tea party. You fill up the pot in the basement and set out the cups and saucers while your sister prepares a plate of Petit Ecoliers, water crackers, and pimento cheese. You tell each other of the gossip at work. About who you suspect to be flirting with you. You argue over whether or not you should get a T.V. for the house.

A year passes and a woman and her two children move into a neighboring house. You and your sister love this woman. She is just a hoot. She starts joining you for your tea parties while her children are at their clubs. She loves to bring these cranberry and fennel wafers that you and your sister can’t stand. You laugh about how you managed to avoid them when she leaves.

Another year passes and another woman moves close by and she has such a gentle spirit that she’s completely undeniable. She brings orange slices to your tea parties. The next year, almost at the top of it, your gentle friend receives a ride home from her boss. She runs in to ask if she can invite her boss to your little gathering. You and your sister say of course. The boss is a nervous woman who walks around with her hands clasped at her chest and when you ask her how she takes her tea she says, “Well, hmm. I think that. Well, what do you recommend?” How could you and your friends not fall in love with someone so perfectly anxious? She starts to always give rides to your neighbor and stay for tea. You and your sister talk about how lucky it is just how much you enjoy all these women. You talk about how dear they are to you, about their odd fashions and the silly things they say.

Each year a new friend joins the tea party and after fifty years of living in your aunt’s house, the tea parties each night are a complete rager. So many new snacks have been added and you and your sister have hung lights in the garden. People bring their own cups now and clean-up is a breeze. Different pots are constantly in rotation and women are always running up and down the basement stairs to refill. Not everyone can always come but there is always at least one or two nights a month that work out where all fifty-two women lounge about drinking tea and sharing themselves with each other.

After year fifty, the number of friends starts to drop off. Ladies start dying and new friends aren’t added. Thirty years pass and just you and your sister are left at the party. You are one-hundred-and-ten and one-hundred-and-twelve years old. You talk often of your sweet dead friends. You say to your sister that sometimes you miss those large parties. Your sister says, “Yeah.” Your sister spreads a little pimento cheese on her water cracker and says, “You know, though, it’s nice too when it’s just us.”

A meditation walk each day has started to help with your anger. You’ve been reading your Bible in the morning and as you walk you think about gentleness moving as a strong wind through your life. You picture yourself as a house and when you walk, your windows and doors are wide open to let this wind come and sweep away feelings of anger, of pride, of conceit. At first it feels a little phony but then the things that used to make you so mad start to wear on you a little less. When your neighbor weed whacks his yard at six A.M. on a Saturday, you don’t try to sleep through it, rather you begin your walk early and comfort yourself with the thought that if you’d like, you have time to nap that day. You start to really believe that people’s interest in television you don’t like is a positive thing about them. It’s a positive thing that people are different than me, you write in your journal. My life will be marked by compassion, not contempt, you write in your journal. You sneak into your neighbor’s garage at night and return his rake that you’d stolen as payback for the weed whacking. It is no longer you who lives but Christ who lives through you.

But the next morning your neighbor is found with a knife through his eye in the garage. It happened in the morning. His wife has an alibi and your boot prints and hair are all over. They find your fingerprints on the rake. You had been on your walk through town but no one steps forward to say they saw you. It comes out that you had been having ongoing disputes with your neighbor. No one seems to think your newfound “lightness” is worth mentioning. You are taken into custody. A few weeks go by and then you are released. One of those trashy television shows your coworkers like was shooting on top of a penthouse the morning your neighbor died and whilst doing a scan of the block below, they caught you on tape. You have an alibi. They never catch the killer and you hear of a few more murders in parks and alleys but you are free.

The story gets attention in the news. You and one of the stars of the trashy television show are interviewed on a talk show to share your experience. The star of the show is what you would describe as a knockout. She has long wavy hair and big eyes. Her lips are big too and they seem to be real. Her skin looks like it has the sun inside of it and she wears these outfits. She talks to you before and after your interview and invites you to go swimming in her pool.

Her pool is heated and the water feels sort of thick and velvety. You ask the star if she likes to go on walks. She says she doesn’t really have time to walk these days. You ask her to go with you the next morning. You’re a little afraid this thing that is happening is just about tonight and you don’t want it to ever end. When you leave her house, you ask her to meet you outside the penthouse in the morning to walk where you and a sparrow that flew by were caught on camera as not guilty. In the morning she is there.

A million dollars is deposited into your bank account accidentally by Wells Fargo. You immediately buy a house and a car and pay off your student loans. By the time they sue, you’ve gotten a good lawyer and the lawyer wins and you get to keep what you’ve got.

You have fun, real fun, every birthday and every New Year’s Eve.

You are born with a disease and will only live for one hundred days. Your mother does not want you and they can’t convince the father. He says he wouldn’t do it right and you are left in hospice care. You are adopted into foster care almost immediately by a woman named Anne. She brings you home and keeps you warm. She sings you songs and kisses your cheeks. She takes off her shirt and lets you rest against her chest and it feels good. She puts this little cap on your head that she knitted for you and says, “Now who’s the most handsome man in the world?” It is so soft. When she takes you back and forth from the hospital she calls it your special date and always takes the Belt that goes by the ocean.

With twenty-five days left to go in your life, you can only stay in the hospital. Anne still comes in every day. She hangs a mobile above your bed and sings you to sleep. She wears bright colored outfits and even when she can’t pick you all the way up she holds your little head in her hands. On your ninety-eighth day of being alive they let Anne take you back home. You are in a lot of pain but you’re glad to smell this place again. On your last day Anne cries and sings to you. She tells you how much she loves you and how wonderful it is that you were a part of the world. She says she is so happy to know you. She tells you all her favorite memories of your one-hundred-day life. She shows you a picture of the two of you together and shows you where she’ll keep it in her house. She holds your hand when you die. Of your one hundred days on earth, really only the first few were not great. For the rest of your life you were totally in love.

Jonny TwoxFour is from Virginia. She is a recent graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is the winner of the James Knudsen Fiction Contest and has work in Electric Literature Magazine.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE