Valentine’s Day

By Xia Jia, translated from the Chinese by Ken Liu

Neither Chen nor Zheng had girlfriends. On Valentine’s Day, as they watched their roommate Huang get all dressed up to go out, they grabbed him by the arms and said, “Come on, pal, how about letting us tap into the feed for your date?”

“We’re just going to dinner and then taking a stroll together,” said Huang awkwardly. “It’s not very exciting.”

“If it’s not that exciting,” said Chen, “then you wouldn’t mind if we tap in.”

“Exactly,” said Zheng. “We just want to take a peek. We won’t give you any trouble.”

“Besides,” said Chen, “without our excellent advice and selfless service as coaches, do you think Qing would have agreed to go out with you?”

“A good friend should be generous,” Zheng added.

Huang was no good at this sort of argument and in the end gave in. He put on his contacts and adjusted the settings to broadcast everything he saw onto the wall of his bedroom. Then he hurried out so he wouldn’t be late for his date.

#

Huang and Qing met up outside the campus gate and went to a Western-style restaurant for dinner. The restaurant was new, with classy décor and prices to match. Huang had been scoping out the place for a while and finally made up his mind the day before to make a reservation. Holding hands, the two approached the restaurant and saw several well-dressed, potbellied men arguing with the host at the door.

“We’re regulars!” said one of the men. “We come here almost every week. Why can’t we go in today?”

The host blocked their way but remained courteous. “I’m really sorry, but you know today is special. Only couples with reservations are allowed. I really don’t have any open tables. Please come back tomorrow.”

The man’s face grew red, and he was about to start shouting when one of his friends grabbed him. “Forget it. Arguing isn’t going to make any difference. Let’s go somewhere else.”

Huang watched the disappointed men leave and glanced at Qing, feeling pleased with himself. The host checked the reservation list and welcomed the couple.

They sat down and ordered. Just as they were finishing their appetizers, the restaurant’s manager came over with a bottle. Huang looked at the label and knew right away that the wine was not cheap.

“Wait!” he said. “We didn’t order any wine.”

The manager smiled. “You two have the highest attention rating in the restaurant. From the time you came in, we’ve already taken more than thirty reservations. This bottle is on the house as a token of our appreciation, and you’ll get a twenty percent discount on your bill.”

Huang was baffled. “Attention rating?”

“Check for yourself.”

Huang had a bad feeling about this. He took out his phone and checked the feed from his contacts. Somehow the live feed had been turned into a public broadcast, and tens of thousands were now tapping in.

Many were leaving comments below the feed:

– Lucky guy! She’s a 9, or at least a high 8.

– She needs to see an orthodontist though. Look at that gap in her teeth when she smiles!

– I know those dudes they turned away earlier! They work in the office next to my company, LOL.

– I like her shoes, but I can’t tell the brand. Hey buddy, you mind bending down and leaning in so I can get a better look?

Many of the comments disgusted Huang and made his blood boil.

“What’s the matter?” Qing asked from across the table, looking concerned.

Embarrassed, Huang rushed to explain. Then he grabbed her hand. “I’m so sorry about this. Please don’t be mad. I’ll shut off the feed right away.”

Qing sighed. “I’m not mad. I feel sorry for them, really. They feel lonely and abandoned on Valentine’s Day, and it’s not a big deal that you let them tag along. Let’s just shut it off and ignore them. They’ll get bored and stop soon enough.”

Huang was moved by Qing’s generosity. He shut off his contacts and his phone, and they continued to chat over dinner.

As dessert was served, a young man barely in his twenties came over from the next table. He put his hands on their table and leaned down to speak to Huang.

“Listen, um … I have a proposal. Someone posted a dare online to see if anyone at this restaurant has the courage to kiss your girlfriend. It kind of went viral, and he raised ten thousand yuan in half an hour. Honestly, I don’t care about the money, but it seems kind of fun, right? If you agree, you and I can even split the money. My girlfriend already said she’s fine with it.”

Huang looked over at the next table. A heavily made-up young woman smiled and waved back. Couples at other tables were all staring at them, and some held up their phones, ready to capture the moment. He looked up at the young man and saw a dim red light winking in his left eye—he had been broadcasting his live feed this entire time.

Huang felt as though the air around him was filled with people straining for a peek. He was going to suffocate under their gazes.

Qing stood up and stared at the young man.

“Get out of my way,” she said.

After a few seconds, the young man shrugged and stepped back. Qing pulled Huang out of his chair. “Let’s go.”

They payed at the cash register and left the restaurant. Still holding hands, they ran until they had turned a corner. They stopped and gulped the cold air of early spring.

“Where do you want to go now?” Qing asked after she had caught her breath.

Huang looked around at the glass shop displays, the screens filled with ads, and the eyes of other pedestrians—everything seemed to have a dim, winking red light. He frowned, deep in thought, and then his face brightened.

“Let’s go see a movie.”

A theater would be dark, and no one would bother them.

“Good idea,” said Qing, smiling.

The cinema was also full of couples. They picked a movie that was about to start and bought some snacks and drinks before going into the theater. The lights dimmed and the whole theater went dark. Huang felt himself finally relaxing.

After the movie started playing, he felt Qing slowly leaning over and resting her head against his shoulder. Waves of sweet joy filled his chest. He looked down, mesmerized by the flickering shadows across Qing’s face. Her lips were so full, like a flower about to bloom. He wondered if he should try to kiss her, but he didn’t want to be presumptuous. He hesitated, waited, and just as he was about to take the leap, the giant screen went dark.

Huang was confused and didn’t move. Then a tinkling song began to play, and the screen lit up with new images. At first, he thought the movie was continuing, but then he realized that he was wrong.

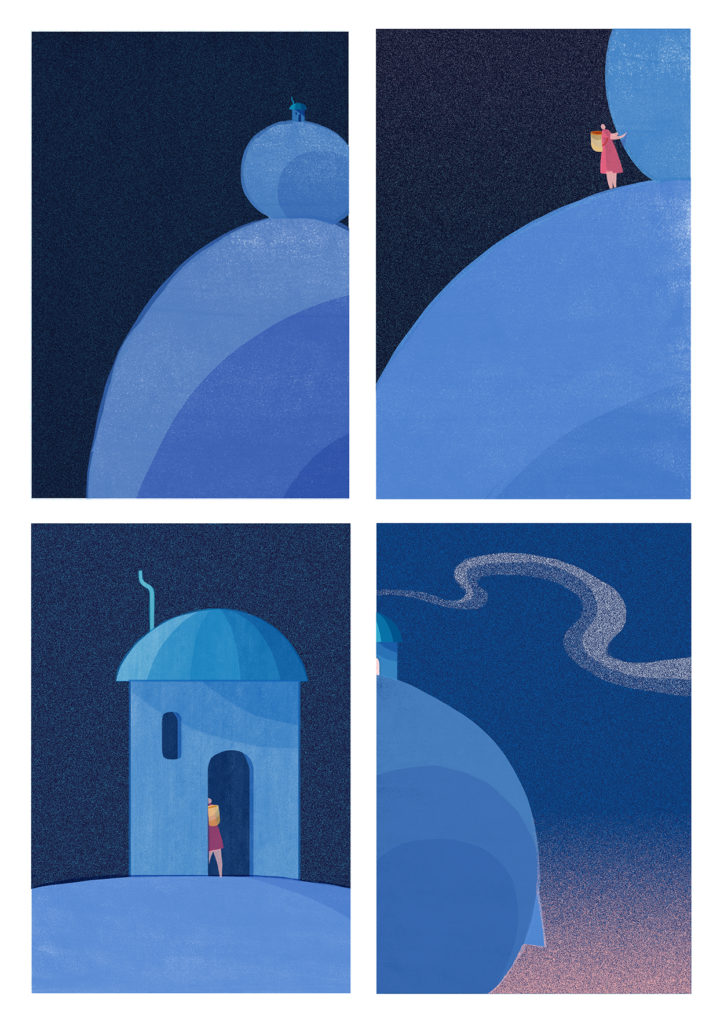

Photographs of a baby appeared one after another on the screen: crying, laughing, blurred, hi-def… Edited together, they flowed like some sort of home movie. Gradually, as the child in the pictures grew up, he realized that these were pictures of Qing. From a baby she turned into a girl, than a beautiful young woman. The music built to an emotional peak, and the smiling face of Qing flickered across the giant screen, lovely beyond words. Finally, the last photograph faded away as the music also trailed off. A bright line of text appeared in the darkness:

Qing, I love you. I love all of you. I love each moment of your existence.

A pause, and then another line:

Will you marry me?

Huang whipped his head around to look at Qing, whose eyes were filled with tears. She swallowed, and tried to speak, “What … what … “

“It’s not me—”

The lights in the theater came on. A tiny figure appeared below the giant screen. As he approached them, a spotlight was trained on him. He wore a black suit, and he held a bouquet of ninety-nine red roses. The spotlight was so bright that it was impossible to see his features clearly.

He stopped in front of Qing, and knelt down on one knee. “Please excuse my behavior. I just wanted to surprise you.”

Qing’s voice trembled. “I … don’t even know you…”

“That’s not so important. We all start as strangers, don’t we? I saw you for the first time today on the web, and for some reason, you touched my heart. When I saw you say to the camera, ‘Get out of my way,’ I decided in the very core of my being that you’re the girl I want to marry.

“I went and searched for images of you and put them together in a hurry so I could come and propose. I don’t care if you’re already with someone, and I don’t care that you don’t know who I am. I just want to tell you, my darling Qing, that I will never marry anyone except you, and I will use everything in my power to love you and to care for you. Please give me a chance! I’ll make you happy.”

Huang felt Qing’s cold hand slipping out of his palm like a fish. He was soaked in sweat, and he felt he was suffocating again. Red lights flickered around him as everyone in the theater stared at them and recorded them. He felt the world turn surreal. Is today Valentine’s Day or April Fool’s Day?

He looked at Qing, sitting next to him. Her face was drained of blood, and her lips trembled like the fluttering wings of a dying butterfly. Finally, Qing grabbed a bucket of popcorn from the seat next to her and tossed it with all her strength at the face of the stranger.

She screamed at the top of her lungs, “Get out of my way, you crazy—”

#

Huang accompanied Qing back to her residential hall, both in low spirits. Around them, behind trees and bushes, they could see couples with arms wrapped around each other, saying goodbye.

Qing started to climb the stairs before the building door, stopped, and turned around. She tried to smile. “It’s not a big deal. It will pass.”

Huang nodded. His head was filled with a buzzing that made it impossible to think straight.

“Don’t be angry at your roommates,” Qing said. “You still have to live with them.”

Huang nodded again.

Qing said, “Stupid people will gossip, and you can’t stop them. But someday, they’ll stop and forget about you and me.”

Huang nodded.

Qing said, “Let’s … take a break for a while. We each have to take care of ourselves. Maybe later, after this is over …”

Huang didn’t nod, and Qing said nothing more. She turned and entered the residence hall.

A new moon climbed to the tip of the tree nearby, and the branches rustled in the night breeze. Huang stood for a while, gazing up at the moon. Then he slowly began the walk home.

As an undergraduate, Xia Jia majored in Atmospheric Sciences at Peking University. She then entered the Film Studies Program at the Communication University of China, where she completed her Master’s thesis: “A Study on Female Figures in Science Fiction Films.” In 2014, she obtained a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature and World Literature at Peking University, with “Chinese Science Fiction and Its Cultural Politics Since 1990” as the topic of her dissertation. Now she is Associate Professor of Chinese Literature at Xi’an Jiaotong University. She has been publishing fiction since college in Science Fiction World and other venues. Several of her stories have won the Galaxy Award, China’s most prestigious science fiction award. In English translation, she has been published in Clarkesworld and Upgraded. Her first story written in English, “Let’s Have a Talk,” was published in Nature in 2015.

Ken Liu (http://kenliu.name) is an author of speculative fiction, as well as a translatgor, lawyer, and programmer. A winner of the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy awards, he is the author of The Dandelion Dynasty, a silkpunk epic fantasy series (The Grace of Kings (2015), The Wall of Storms (2016), and a forthcoming third volume) and The Paper Menagerie and Other Stories (2016), a collection. In addition to his original fiction, Ken also translated numerous works from Chinese to English, including The Three-Body Problem (2014), by Liu Cixin, and “Folding Beijing,” by Hao Jingfang, both Hugo winners.