Content warning: forced medication, needles, blood, death, parasites, unsanitary, sex, body horror

Plateau 1001

Now is afternoon and the waves wash quietly on the lake Pawnee’s lips. Children cry at the edge of this cool reservoir, some hard line between land and water, a boundary at once uncrossable and enticing, beckoning onlookers to drop on in, fall, dissolve. Sunglass-sporting and through-the-shadows-of-visors-creeping women are laughing and pointing in our direction, toward two bodies planted firmly in the sand, fixed to one another.

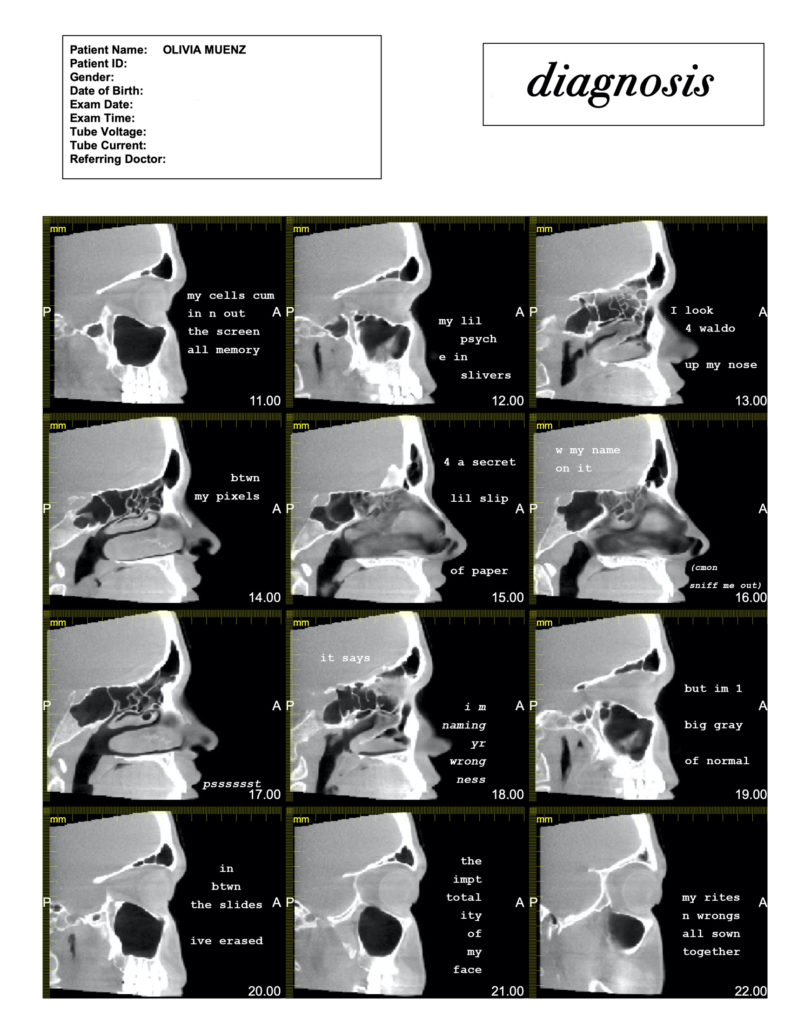

“They are laughing at me,” I say to Giovanni, weakly, stumbling over myself, snaking my hands through the damp sand, hoping to find something to grasp onto. Gasping for air, the chest constricts. My resting blood pressure is 142/98, but I can tell it is higher now, at or approaching crisis; untreated hypertensives have a way of knowing these things. Best understood as spiritual, knowledge of how the rust is moving comes naturally. The force under which it circulates… this stuff is easy to discern. We can imagine how far the blood would spurt if we removed the arterial walls, made naked the surrounding flesh; this process determines our blood pressure without the use of a cuff. I threw mine away three months ago, flushing a bottle of eplerenone in the process, the doctor’s words ringing in my mind, Take this twice a day, it will help. If only it were not placebic.

Gio takes my arm and says, “No, they aren’t.” I can tell he’s lying by the way his chin moves as he speaks, barreling to the left, his left not mine. The ultimate sign of deceit. All liars move their chins this way when they speak, one trait among countless others I’ve picked up on. “They are not laughing at you, come and sit down,” he says. I realize I am standing with my arms crossed against my bare chest, facing the women. Another sign of lying, it is known, is demanding that one closes a physical gap, some attempt at repairing the broken sacrament, skin touching skin increasing serotonin in the cleft, dopamine. Chemical concealment.

I sit down between his outstretched legs, laying my head on his body. He works his hands into my shoulders, stained with those small, red bumps, the ones inherited from my mother. People start to stare at us, staring this time not at me in particular, but at the closeness of two men, of male intimacy gone public. What is wrong with me, I want to ask him, why am I this way, why am I so defenseless and broken, why is the world centered on me but in the most denying ways, but the answer to each is clear. “They were laughing at me,” I repeat, “but I trust you.” I attempt to convince myself of this. My hands, working through the sand, catch on something sharp, and my mind turns now to syringes. Long acting injectables are reserved for those who need antipsychotics, but who forget or refuse to take their medication. Creating a localized mass in the body, intramuscular, deep, raw, that gel finds itself implanted and absorbed over time, a month, three months, it depends. My haloperidol decanoate appointment is three months overdue as the foam rolls rhythmically over itself, back and forth, in, out.

“Amorito, do you want to go swimming?” he asks while patting my shoulders and standing up. The sand, brown and clumpy, falls off his body, returning to the source, hourglass-like in form and function. Some amount of time has passed, but how much is unclear. The women are no longer there, the sun has moved in the sky, the foam coating the edge has changed shape, flatter now. The snaking of time yet again escapes me. “Come on, you’ll love it. To float, become nothing at all. Emptiness in the middle of everything, the center of a wide-reaching circle.”

The day and my body slip away as I swim, the low waves reaching the shore and the sun receding past the horizon, brown and aching. “Let’s make a fire, Gio,” I say as we pass in breaststroke. “As tall as our house, let’s make a fire hot enough to scorch the dirt and melt down our rings, hot enough to pierce through the sky’s skin.” We approach the waterfront, soaking still, and as if under a trance, time flashes by once more: the wooden platform finds itself built in but a moment, our bodies as ants trickling around the artifice. Soon ablaze, it swells to a diameter wide enough to swallow both our bodies whole, large enough to consume and make into ash my heart.

And the smell. Gio and I met at an Omaha acreage, a support group for HIV-positive men, with the fire shimmering blue-hot, crackling, the burning sap giving off that almost-sweet smell I recognize in the fire just ahead of me know. He said to me then, “You look nice for a dead man.” We were being torn apart from the inside, but he carried himself with an air of confidence unlike any other, his shirt crinklefree, his back straight. The kind of posturing learned only through the rough obedience of private school, Catholic, or maybe preparatory. “When did you catch this miserable bug?” he asked, and I told him the story of seeking, of catching, seroconversion alone in a dorm as those so-worn sounds of life were extinguished deep into the evening. That night, my eyes ran dry, the blood pounded against the temples, and on every beat, the vision blurred as so many halos, circular yet jagged. “In algebra,” he told me, “the simplest object is a group, and his complicated partner is the ring. There, as here, navigating groups is simple, but when it comes to rings, it all falls apart.” We talked as the night stretched itself into the pale blue of day, going home together, hand in hand, laughing and full.

“Is everything okay?” he asks me. “You’re losing yourself again.” Now I am staring into the gargantuan fire with my face all wet and my tongue salty, the night sky black, punctuated with so many stars, a weblike structure expanding every which way. I nod, grab a lob to sit on, one outcropping of twigs just barely hanging on to the base, and I start to open my clenched jaws.

“I have pinworms,” I say. “Enterobius. I haven’t seen any directly, but all of the signs are there: itching in the shadows, insomnia, appendix pain. I have a pinworm infection and I’ve known about it for a year, maybe more. Every month or two I buy all the available pills, but I throw them away. I can’t bring myself to kill them, and even though they’re unseen, there they are. If you listen close enough, you can hear them sucking at the side of the bowl, gurgling and splashing in the water. I am being eaten alive. It’s a bit scary to admit it, but anti-pinworm medication is just like trizivir. These pills just make them lie dormant, waiting for a moment to reinfect, multiply, to take you over again. It does nothing but destroy a few and make the rest stronger, killing you faster in the end.” He looks in my eyes in that Gio sort of way, his head cocked, his eyebrows dug in something deep.

But this drops away, and suddenly I am thinking about the blades in our medicine cabinet. Feather is considered the most effective brand. They are aggressive, those slabs of stainless steel: the sharpest consumer blade available. They are so strong that every time I run the razor over the back of my head, I nick myself. The scalp has a rich blood network supplied by five thick arteries, three from the external and two from the internal carotids, nourishing the white psoriatic skin and thinning hair, and whenever I make a pass with the handle, these vessels just start to seep. All these cuts accumulate and start to paint the back of my shirts as so-vibrant watercolor. Sometimes, I run my tongue on the stains, to bring them out, to repair the underlying fabric, to return the natural hue. This fails. I find myself vomiting immediately, the metallic taste overwhelming, dull. But the first time I shaved my head at the age of twenty, the age my father was when he, too, first shaved his head, I forgot to do the neck. Gio held my head in the pit of his elbow and said, “You forgot to get it all. Let me do it.” He turned me over and applied clearance-rack shaving gel, my face laying in the divot of the sink, water flowing over and around my body, the follicles softening, open. With one stroke, the entire epidermis sloughed off, and with it the band of skin underneath. Blood gushed out and filled his hands, soupy, hot, spurting and so very thin, quickly hardening into something gelatinous. Thick. Mealy. The steam, or maybe it was the smoke, filled the air, hotboxing the two of us in my own filth, the body spoiling, releasing fumes, toxic and overwhelming. “I am so sorry,” he said over and over. “I never shaved with a razor like this. I wanted to help you.” Contagion spilt. He tightly wrapped my neck in bandages, licking his fingers as he grabbed new spools to contain the damage. Contagion spread.

“Let’s go home, amorito,” he says as he throws water over the still-raging fire. “You are tired. I can tell you’re not feeling well. Let’s grab our bikes and go.”

I run ahead of him. “Catch me if you can!” I yell back, my feet slamming against the packed dirt of this great hill, repetitive predictable. It takes all of a minute to get to the bike racks, and I breathlessly unlock them both, waiting for him to arrive.

His body now comes into view from beyond the crest. “Did you miss me?” he asks, running at me and jumping into the saddle of his bike, pedaling without waiting for a response. I nod anyway, and so off we ride, the red-flashing lights behind us, the white luminescence ahead.

With the wheels tucked in deep, rutlines snaking past the cedar and oak, I have a hard-on. Spokes clicking. Each tick is some sort of relief, the whirring, wobbling of the metal a kind of assurance. It is a reprieve, the passage of time, calculable by the counting of loops. One’s body as a spring stopper for doors, a generalization of the bikemetal’s murmur. A great cycle. Push and be pushed, brought to climax. And I ride eastward in hope of a life never promised to be mine, in the form of a double-layered stopper, the turgid body with this peculiar outgrowth, cancerous by function if not by form. Truthfully, a life of happiness, fulfillment, was promised to nobody, but especially not a vein-marked boy with a trembling cock growing by nothing but subtle movements of the flesh, of the man biking on my side. Just beyond arm’s reach. Tanned calves and the tapering off of the waist. Evading twigs and leaves with grace. Pouncing.

We stop after an hour of this, pushing ourselves and the bikes into a clearance not much larger than a house, a grove of trees, ferns, bushes swaying in the wind of so-full night. “Sometimes it feels as though I have died and inhabit a rotting body,” Gio says. “My heart and lungs are filled with formaldehyde and I am dead or dying and the world continues spinning on its axis without me. Arnold Pyle died 47 years ago. I painted him, and my painting is showcased at the Sheldon.”

The plains are rustling. Native grasses and wildflowers bloom over and beyond the horizon. Purple, I think to myself, illuminated in the moonlight, but I can’t quite remember what they look like in the dappled sun. Withered from drought, probably, this year was as hard as they come, but radiating color anyway. The great expanse unfolds. “I wrote a letter to him before he died. It’s all stored here.” He points to his temple. “The great repository.” A beat. “What are you thinking about?”

“I’m thinking about what you said,” I say. I take in the view, the air, the way the wind feels as it beats against my sweat-soaked shirt.

“What do you mean?”

“What you said, about Pyle, I’m just thinking about it.”

“I didn’t say anything.” Now with the cocked head, the brows set deep on the face. “Are you okay? Do you need some of my water?” The wind has stolen all the heat from my body, and I start to shiver.

“No, I’m okay. Just daydreaming. Home.” I point.

He nods, turns around, and starts to pedal as I follow. The calves stretching and retracting. Constriction. About twenty feet ahead, too far to talk comfortably, but close enough to hear if you listen close. “Sometimes I wonder how long I have been dead,” I hear him say. “How many reunions have been lost to the annals of time, empty or emptying. Struggle in these times. Mythologizing unlike any other.” But this is how we ride, huffing as the Fuji and Canyon dart beneath us, between our stretched bodies.

As his body runs away from mine, the distinctive wobbling of the bike sends me back. The first time I held a man was the summer I turned eighteen. I rode my bike with a buggy behind me both ways to school, under the same sun along the same path, winding and growing along Salt Creek to the east of downtown Lincoln, marshy and muddy, that he rode to and from work. Silent and meditative, we rode alongside one another until he flagged me down and pulled me into the darkness beneath these great, swaying, cottonwood trees, the popcorn shade to which I am allergic. And with me sniffling and sneezing, he dug his fingers into my collar, pulled it and the belt off until he left my body exposed, wiggling out of his worn clothes, soon connecting together as one. He told me, “You know, I’ve never done something like this, I’m straight.” And while slipping back into my skin I thought, Yes, me too. Once a week we would stop at that enclosure, bathe in the darkness and silence and it was all I imagined it would be. Come and go and cum and go, feeling and being felt, seeing and being seen.

Yellow light. A mirror reflects a coffee table with a pitcher of water. We are not on our bikes anymore but rather home. “What’s happening with you?” he asks, appearing to my left, our bodies facing one another. A gift only in name, we are sitting between the arms of his father’s old sofa. Torn apart, in shambles, it was destined for the dump. Pictures of us hang on the smoke-faded walls, an image of wholeness. Gio and I smiling in Wien, in Las Vegas, wrapping our arms around one another, merging the bodies, kissing cheeks and giving thumbs up. The frames are old, found in my mother’s attic, the kind given away rather than sold at garage sales. The paint is stripped, the wood is flaking. Whenever I run my fingers over the rough edges, splinters embed themselves in the skin, puncturing the boundary, spilling blood and creating a site of infection. Bacteria, viruses, fungi grow and multiply. It is something wicked, the way they are able to grow without impediment: the clumps of biology traveling throughout the arteries, veins unable to contain them, totally ineffectual, diseased and burgeoning. He puts his soft hands on my knee, one, two, three times, patting and reassuring me, rubbing the oil of his palms deep into my skin, so deep that he replaces my blood’s plasma with his. Chimeric, I am now a parody of myself and Gio, grappling with two destinies at once, all for the price of one. I can feel the DNA shifting, the nucleotides warping whenever he touches me, as though the polysaccharide ladder is being caramelized. I am liquid, overflowing myself.

And now I am not here, but in the cloudy reaches of memory. The first time I was held by a man was my sophomore year of high school. With the sky burning, he took me out to the country to watch the sun devour itself. “Anh,” my boyfriend said, a Vietnamese term of endearment for men, “you are the light of my life.” The corn waved altogether in unison, as if in anticipation, the way it seems to move just before rain nourishes its so-repulsed roots, knowing. Two boys on the wide-open prairie, I thought, utterly exposed. He took me in his arms, holding me as though I were a child in need of comfort or consolation. “I want to kiss you,” he whispered in my ear. I want you to kiss me, too, I thought. I want you to kiss me and bite my lips, eat my tongue, I want you to suck up the roots that lie beneath the teeth and digest me, I want my throat to be exposed to the sun as you leave me here all alone, I want you to cannibalize me, I want to be made an object made legible only through consumption, I want my identity to peel away and be forgotten, I want the skin to melt away as I am made invisible, I want you to spit in my mouth and build me up as a garbage receptacle, I want to be called a Republican as some kind of revenge against those who hurt you, I want crows to find me and rip me to pieces and I want you to be the proximate cause, to be my first. But instead, a tractor rolled up behind us and we flew off back home, our mouths untouched until we were in my driveway, masked in darkness and the smell of cottonwood, moving quickly to evade detection. “I had a good time,” he said, planting a kiss on my lips, rubbing into my chest and my ass, as I rubbed his hard cock through his jeans. “I had a good time and I want to do this again with you.”

The yellow comes back into view. I can hardly remember what he said, so I wait a minute to develop a response. Gio’s face is warped in that so-Gio way. “There’s nothing happening,” I conjure up, my chin moving to the left. My senior year of college is upon us and I teach single-variable calculus, the study of change, what lies beneath a line. Boring, machinic, an overreliance on the straightforward applications of arithmetic, the subject is worthless. The subtle tricks of abstraction ignored, falling in favor of a prescriptive regime of power. “I’ve just been stressed about school, work. The semester is almost over and they haven’t learned anything. I am worried about what the future holds, living in a time of pandemic, of loss and disease.”

“You know that’s not what I’m talking about.” The clock strikes 5:27 and his eyes meet mine. “And we have lived in pandemic our whole lives. What have you been thinking?”

“I haven’t been thinking of anything,” I offer, my mind wandering elsewhere. The spring I turned fifteen, people started reading my thoughts and putting others in my head. Proof is abundant, everywhere, we are so steeped in it. I’d think of a sequence of numbers, and immediately those around me would perform a series of actions to confirm they got the message: two sneezes, one dropped pencil, a dozen spoken words. They would blush whenever I thought of something risqué. Implantation occurred irregularly, so it was always a surprise, but my mindwriters would make me think about formulas embedded in the faces of clocks. Looking at the façade when it is precisely 12:36 says nothing other than the sum (and even the product) of one, two, and three is six. Six carries a special meaning. Baked into the fabric.

“I’m exactly as I always have been, just stressed, overwhelmed.”

Overwhelmed, I think. Last winter, Gio’s skin turned translucent and flaky. The bags under his eyes sunk deep into the sockets, as though there were no bone supporting the muscle, nerves. The veins were bulging against his taut skin, wrapping around the cranium, the fascia of his throat, making his body a sickly quilt of off-whites and purples and blues, more alien than man. His tan had receded, replaced with ghostsheet. After a few days of this, I asked him what was wrong. That Gio stare, before he relented. “My mother called about a week ago,” he said. “I told her about you and the rings,” he could not bring himself to say engagement, “and she blocked my number. I am disgusted with myself. After all of my schooling and training, after all this promise, I live with a man in a small house at the center of a conservative Nebraskan town where we get stared at, and since I was deathfucked as a teen, my own cells kill themselves because of some rogue and treatment-resistant recombinant dual strain hiding in the brain, destroying any hope I had of being a thinker, of ruminating on the questions lying in the intersections of math and love, or of having a life worth living. The future has been taken from me, and now my past is out of reach, too. Nothing of worth has ever existed or remains here.” He pointed down, bursting into tears. “Nothing here.” I took him in my arms and rubbed his back. I wanted to tell him, No, you have nothing to be disgusted with, or no, our house is big enough for both of us, and when you get cold and want your distance, it’s big enough for you to sulk silently and out of view, or no, this disease does so many despicable things, it makes us weak and nauseous and vulnerable and makes the body falter, but one thing it does not do is empty you of value, or no, the virus may lie dormant in the brain but it does not disrupt yours, yours is too full to ever be emptied. But instead, I said, “I am so sorry, my heart. I am so sorry. I am so sorry,” as he filled my shirt with tears and snot.

“Things are not okay with you,” he says. He stands up to turn the radio on low, NPR or some other talk station about the upcoming election. There is something afoot, the broadcaster says, and this is deeply unnatural behavior, never before seen. “I’m worried you’re falling again. Every time this happens, it takes something deep and intractable for you to get help again. It’s an impossible ask, like asking a kid to be introspective, curious.”

“Unplug the radio,” I say. (My speech has been slurred since infancy, tripping over itself, fluid and meandering, the letters melting into one another, r’s finding themselves misplaced, appearing from nowhere. On our first official date, Gio asked me to repeat every sentence. “It’s kind of cute,” he said when we got back home. “The slurring, I mean. Unable to find stability, language itself becomes incoherent. Most gays have a strong command of language because they’ve got to, sibilance maybe being the exception. But slurring is something faithful. Like the muscles in the mouth and throat have been displaced, altogether too human. A great regret of mine has always been my decision to repair my speech in elementary school. I was forced to go, but I could have resisted, I could have kept the malleability of the letter beneath the teeth, along the tongue, intact.”) “Please just unplug it.”

“Why?” he asks. “There’s nothing wrong with the radio. Just background noise while we talk.”

“They’re listening in,” I say. “There’s nothing benign about it. The transmitter behind the dial. It sends and it receives, both at once, constructed with enough bandwidth to allow information to be sent back, forth, a single beam of particles but sending, receiving, all at the same time. Radio as a double-stranded helix, moving through space, time. When radio was first invented, Marconi allowed for it. It’s built-in to the science, the frequencies.”

“They’re not listening in.” His chin twitches.

###

I am in the bedroom now. There is no light peering in from behind the curtains, so it is unclear how much time has passed. I move to light the woodwick candles, the kind that crack with force as they burn away, as the headlights of some small car flash by.

I remember now the taste of being exposed in the backseat of a green sedan, windows all fogged up in the eleventh grade, being held by my friend until we both got hard and touched one another, soft and supple and, all at the same time, turgid, a man coming around on a bike, shining a light in the tinted windows, underwear and belts all loose in the cabin, the buttons of dress shirts bulging, so very exposed in the white, white light, jumping back to the front seats and speeding off, being chased and chased until we lost him, stopping for a moment, laughing until our bellies and groins ached, and, resuming where we left off, he ripped the fat from my sides and made me into something new, unrecognizable and full.

Gio is standing at the door with his head titled. “Follow me,” I say, and time slips away once more.

###

Today is the day of reckoning. Soon his body lies narrow between the outer reaches of mine, between the downward-facing palms, as sweat fills the air, an ocean thousands of miles from any seaboard, salt permeating through the skin, accumulating in the liver, kidneys, deposits forming crystals whose only purpose is to break off into the blood, passing through the urethra as daggers. The first nude photograph I bought was when I was seventeen, one of James Bidgood’s. It swung on the inside of my handle-less closet, visible only to me, able to be viewed only through the destruction of another handle, the repurposing of the old crystal knobs found in drawers throughout the house, in pursuit of something more. Sat in front of a circle of mirrors, Bidgood’s model has his pants infiltrating the corpus, pulled tight, the interior reflected in and made coherent by the exterior. A thousand lonely nights were spent with the two of us staring into the eyes of the other.

Gio is now of the turned guys and has a gaping hole in his chest and from it leaks the fluid that makes up the night sky, black ink, sweet and high and warm: dark, rotten, fragmented blood, torn by sunlight and heat and the art of holding someone close, piled up, and it is awful, the blood, low and thick and grainy, running out of this poor boy’s chest in a continuous stream in thick, ragged clots, ones with bits of hair and teeth and the nails he bit and swallowed over the years, some painted, pastel and smooth, running on and on, and when I penetrate the skin to best enter that abyss, pools of light congeal and run down the horizon, blotting out the fire-warmed blackness behind, the remaining ribs creaking as he breathes in and out, trickling starlight, falling around burst arteries and through cracks in bones, until the boiling and frozen and black and dead blood mixes with my purity, and I take my hand, pull the skin taut and the jaws open, reaching in to grab a memory of the two of us, and douse myself in the newly-refined gasoline, flammable and warm with the smell of sepia, of being kissed on the cheek at a middle school dance, thinking to myself, what will history say of this, a turned guy getting stoma-fucked while he rots and falls apart at the seams, the perineal raphe of this walking corpse disintegrating and leaving exposed stones to twist and starve themselves, what will history say of the self-immolation of the healthy one, burning it all to feel warm and to feel frozen and to feel rotten tissue rubbing against cold and living flesh, and I stop thinking, continue to envelop myself in melted tourmaline until history slips away, the vastness and the density of it all splattered across my chest, softening the peach-light hair, the two of us trading commodities at a loss, secrets on how best to hold a man, how to make love with tears in your eyes, how to ignore the way that your body is falling apart and the way it resists crumbling, and soon the two of us have our chests held against one another, life and death imparted between the two of us, the infection and the cure, one a chariot and one a jockey of this electric thing, watching the scent of necrosis and renaissance fog up our thick-brimmed and square-framed glasses, and I feel my outer layer of skin start to slough away, tasting the possibility of recovery-as-loss, or is it loss-as-recovery, until the buds fall off as bubble wrap, so many pockets of air and saliva cracking apart the muscle as the water-starved air presses it, warps it, transforming the flesh quickly to dust and then nothing, washed away, the black blood and radiant light quickly moving by osmosis, eliminating movement and the cut-across, seeping into the bones of the living, breaking and folding and cracking them, sucking the marrow out and replacing it with the warmth and allure of becoming phantasma, bloody and shredded apart and broken and mended and whole all at once, blood and vomit and an ocean spread out in all directions, a spectacle draped in black on a great circle around the body, a spectacle contained in the body, which serves no greater purpose than as a site of trauma, and it all slips away. I run my arm over his side of the bed, feeling air and air alone.

Lexus Root is a poet and scholar of queer studies living in Lincoln, Nebraska.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE