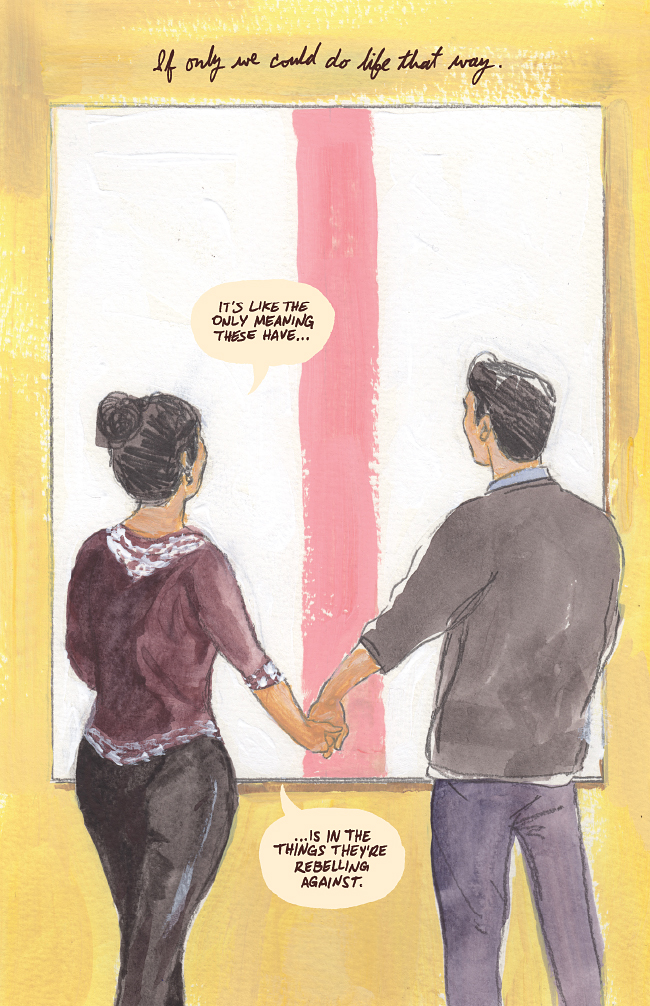

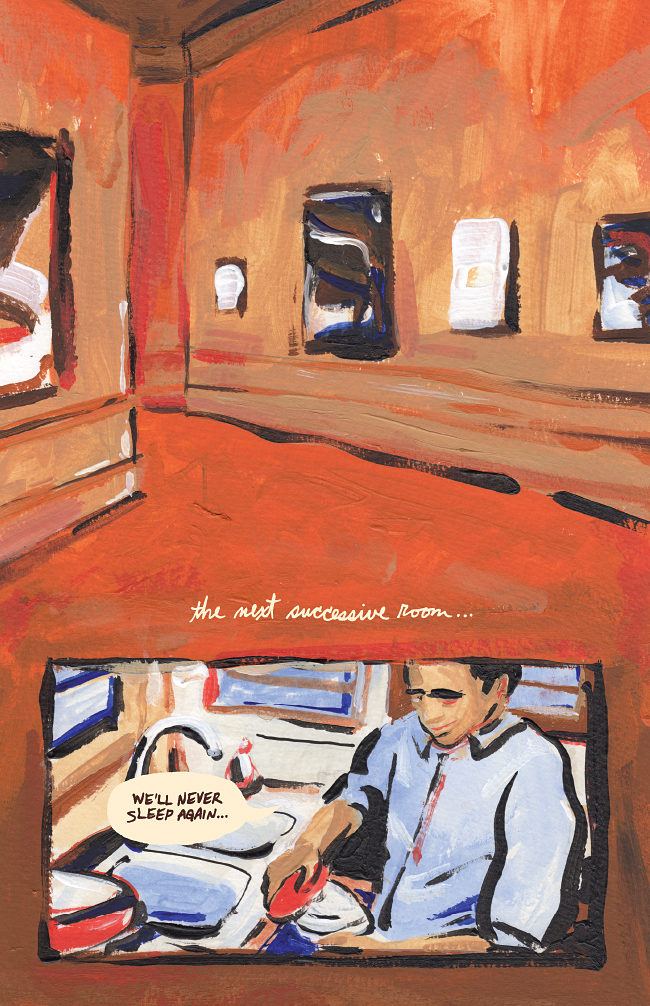

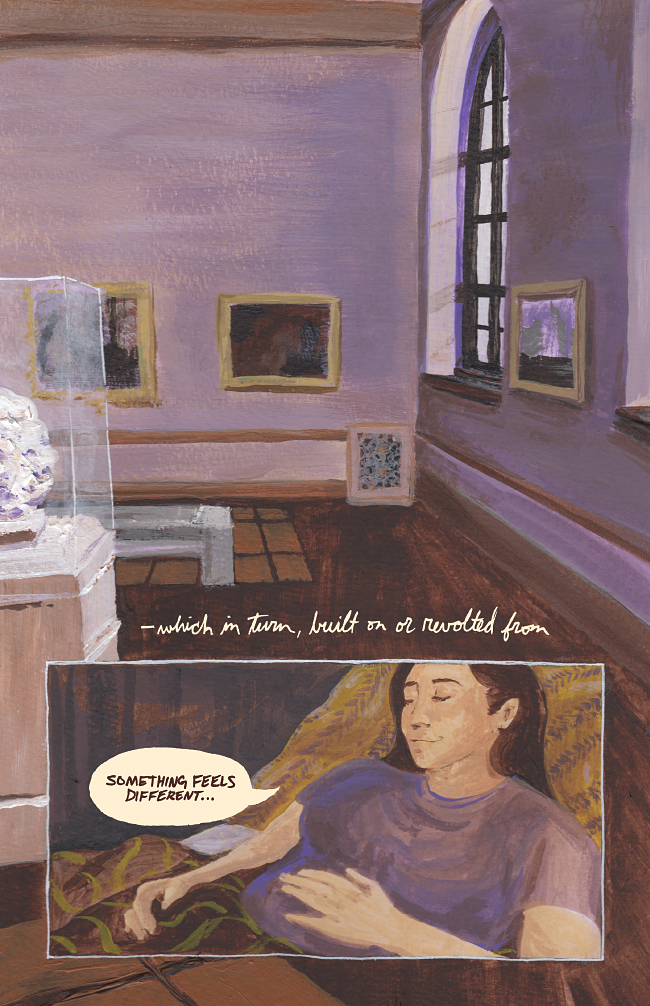

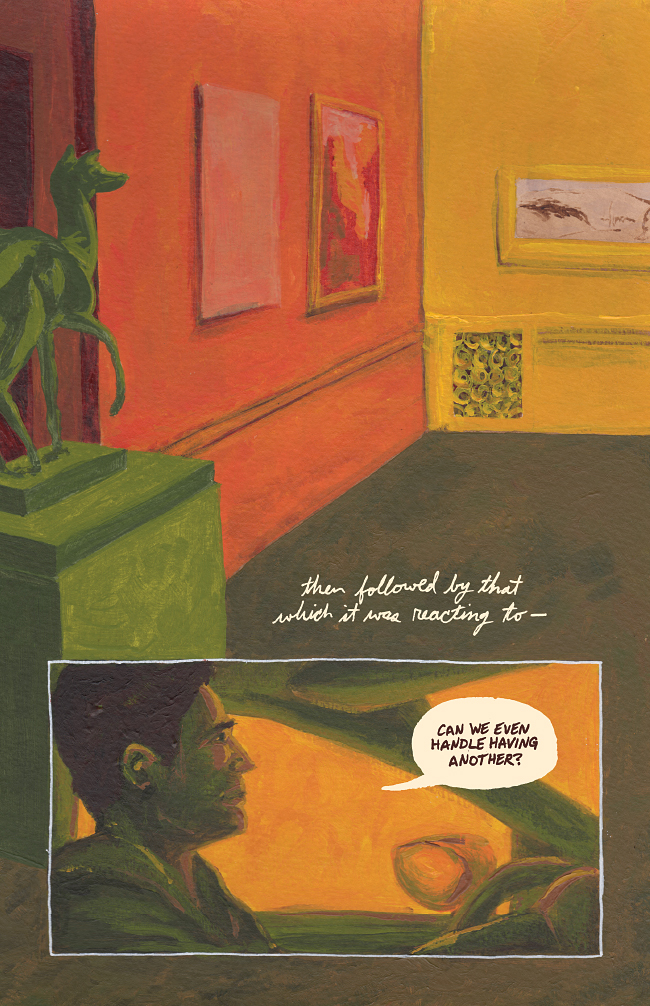

Art in Revolution

Jason Hart is a visual storyteller based in Dayton, Ohio. His narrative works have appeared in Black Warrior Review, Ink Brick, Illustoria, and elsewhere.

Jason Hart is a visual storyteller based in Dayton, Ohio. His narrative works have appeared in Black Warrior Review, Ink Brick, Illustoria, and elsewhere.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOI have a joke for you

What is the only plant that grows

When you feed it blood?

The cotton tree.

Did you laugh?

I’ve been thinking a lot about

ancestry lately,

as I’m stuck still in the trap

of an existential early 20s.

I’ve been thinking about who I would have been

on the continent,

if I should do like the diaspora—

pledge my allegiance to an idea of home

I’ll never be able to corroborate—

claim Ghana, or Nigeria or Cote de Ivoire

as the place before the chains

(my last name is French, after all.)

I took Anthropology in college

and my professor told the class that

Ancestry.com, really any DNA testing kit,

was full of shit,

and a door closed

and my heart broke

all over again.

There were two white people

at my family’s Christmas last year.

They were the only people who got

23andMe kits.

In the first creative writing class

I ever took, the teacher asked everyone

to go around the room,

answer what our names meant

what story they told

Givhan… where does that come from?

Slavery.

I’ve been thinking about the ancestors

as I write a book influenced

by myths from a country that colonized

a good chunk of the world,

ones I’m familiar with

because they were what got taught.

I think about them

when there’s an uptick on Black twitter

of posts saying shit like:

Buck up y’all, they’re dancing in the Kingdom, filled with joy at what you get to do

without them chains. Make their sacrifice worth it. Make them proud.

(or whatever fits in 120 characters.)

I took a class on African Religion

and almost holy disregarded the units

on Catholicism and Christianity,

preferring the flavor of the ATR tales,

like the one where a chicken

helps create the world:

Obatala climbs down a gold chain

and scatters sand from a snail shell.

He releases the bird to go bat shit—

wherever it kicks

a sandstorm of hills and valleys follows—

and the world began.

(I think I should stop eating chicken)

I like to think of the Orishas as my ancestors

when the flesh and blood reality

of historical violence

on bodies that look like mine

starts to consume me.

I think of Obatala and the black cat

brought to a creation myth—

whose only job was to curl up beside him,

keep him company in a new made world—

and I see a way of life

where I don’t have to be alone.

I think of Olokun livid as fuck,

drowning half the new made world

because a man was too stupid

to ask her permission

to enter and terra form her kingdom—

and I don’t feel the history

of Black women powerless,

raped and separated from their families.

I think of Shango and how fucking sick

a Black god of thunder must be—

Static Shock meets John Henry meets Jesus

(but obviously not white-washed Jesus)

and I feel strong knowing

he could beat the absolute shit

out of Zeus, if it came to it.

But then I think of the golden chain

Olorun allowed Obatala

to hang off the edge of the sky

in the first place—

find myself shackled

to the same kind of narrative.

So I’ve been thinking

about ancestry a lot,

but also about theft.

The continental kind.

The kind so huge it can’t be replaced by reparations

(though it’s a good fucking place to start)

The kind that has punched a hole

in the fabric of this history,

a loss so permanent it’s opened a pit in me

that no number of stories could ever fill.

I.

My mother told me once,

when I asked why I never knew

Alabama soil. Blackness. The richness

of my place on this earth

in this tree,

a story about walking with my father

and the truck that drove by

and the people inside who slowed down

to throw bricks at them.

I asked Did you throw them back,

teach them a lesson?

and her mouth said the no her eyes couldn’t,

busy as they were saying something

in a language I didn’t understand then,

horrors I couldn’t pronounce as a child

in a dialect unused to the flavor of lynching,

my white teeth in this black mouth

unable to let the knowledge of death

slip through its gaps.

II.

My father is as Black

as I like to imagine the soil

in that place we were taken from.

III.

The things I know about my father,

are that he used to go to movies with friends,

where one person would buy the ticket

and let the others in through the exit

that he learned how to drive using a friend’s car

because no one in our family owned one,

used to cheat at cards, palm them,

have one up his sleeve to rig the game,

that he walked 5 or more miles a day

to get to a bus that would take him

to a segregated school,

that he grew up using an outhouse,

no indoor plumbing,

and that his parents were sharecroppers,

his father died young.

I know my father has a bad back

from teaching soldiers

to jump out of helicopters,

that the VA hospital gives out cortisone shots

in the years it takes

between insurance claims and surgery,

that he joined the Air Force to get out

of a South so deep and dark,

he still won’t talk about it,

won’t acknowledge that some part of me

is curious what part of her

might belong down there

with the ones who never left.

I know my father had a brother

who died in a motorcycle accident

one who’s a trucker

one who calls occasionally,

another that totaled my father’s car

while he was deployed in Germany,

another that stopped on a highway in Seattle,

threw the car with my mother and my father and himself

into reverse, to take the exit he’d overshot

I know he still talks to Shirley

and one other sister, Ernestine, I think,

that another sister died

unknown.

I know he married a white woman,

had three brown daughters,

that he takes care of four cats

and puts money in my account

when I get scared I can’t afford

to be alive,

I know he didn’t tell my mother

about his family reunion

two summers ago,

that he was silent as she yelled at him

when I let it slip.

IV.

I know that some kid called him a nigger

at his job

and that if I could,

I would rip that fucker apart

tear the word out of his throat with my teeth

scratch our history into his body with my nails

and it still wouldn’t be enough

to keep it from happening again

to erase the trauma of all the other times

he’s been called something

I can’t protect him from.

V.

When I told my father

about getting kicked out of a class at OSU

to make a spot for the white students

who hadn’t gotten in and complained,

he said, Hang in there, kid

because he knows better than I ever will

that you can’t be Black in this country

without having some part of yourself

lynched—

VI.

My father is Black as the soil

I like to believe exists

in that place we were taken from

and he makes me cry

sometimes,

when I think of all the bad things

that could happen to him

for existing here.

VII.

My father is Black as new earth

in an old world we never got to know,

and I thank the god he still believes in

but I never could

that he is my father.

Juliette Givhan is a poet and MFA candidate at Oregon State University. She completed a BA in English with a minor in African American and African Studies at Michigan State University. Her writing explores popular culture, memes, myths, and the intersection of identities—all in an attempt to learn how to survive as a Black queer writer in America.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOYou must be thinking of my grandma’s people.

Must have me confused

with someone else.

I see the resemblance.

But I’m not the one—

won’t be

compelled to cradle

every word on my tongue

behind the caging of my

teeth only birthing

Black ass bon mot babies

for your pleasure.

Bite my tongue?

I’ve heard, hold your peace,

& requests that I stay calm

(& maintain the illusion of peace.

Recall, we’re all happy

if we’re quiet.)

Bitch,

please.

My people trapped sharp

words in the esophagus,

dulled them down on the concrete

slabs of solitary confinement

sacrificed in silence

while carving in the throat

I was here

bold subversive graffiti

scrawled in the night.

The fumes of their words are why

my throat is dry from how often

I refuse to choke gag reflex

fix my mouth.

If you only knew what

I want to say when you utter:

temper your temper

as if a soft word makes palatable misery

as if tongue separates the bitter from sweet

as if it is my party trick to swallow back the bitter pit

as if tying my anger into knots like a cherry stem—

Woo—Ma’am!

Bless.

I am not my grandma’s—

Child, that generation put

up with what they had to.

I never learned how to sweet

and swallow bad produce.

To fix my lips for long,

never rouged them red,

in replacement of bloodlust.

I too want words

soft on skin soft on psyche

lapping softly in my inner

ear revolutionary love words,

like: you matter.

Until then

I let sing,

every word.

I.

In my treasure chest of infinity boxes—

earrings made from the luminescent

light of his eyes, scent a cherry pit

on my tongue, the freedom to take

up space behind my ear,

worship in the temple of my round belly,

fingers that glance along the dimple in his back,

his teeth striping electric over, under

and between where my ass bisects into cheeks,

he moon tides between my thighs,

remind me of hollows between his toes

ripe for plucking—

universes are open for exploration.

II.

He and I consume one another

a curving ouroboros, slick

and primordial, a daisy chaining

organism, closed loop of two,

we claim and conquer in the name of

leave forensic evidence on our tongues

savor skin as soft and salt laden

as butter pecan ice cream

sipped from God’s own mouth.

Angelique Zobitz has work in or forthcoming in Sugar House Review, The Adirondack Review, Obsidian: Literature & Arts of the African Diaspora, Yemassee Journal, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Poets Reading the News, So to Speak, SWWIM, Rise Up Review, Rogue Agent, Pretty Owl Press, Mom Egg Review, and Psaltery & Lyre amongst others. She is a Spring 2019 Black River Chapbook Finalist and a two-time 2019 Best of the Net Anthology nominee. She lives in West Lafayette, Indiana with her husband, daughter, and a wild rescue dog and can be found on Twitter and Instagram: @angeliquezobitz.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOOn my chest slopes a continent

old, smelling of sun-baked grass,

its prairie rooted in my sternum.

Here, in the darkness of my ribs, I carry

first mother, someone like possum, my stretch marks a border

where she shed scales for fur.

She laughs at our new carnivores and their sloppiness,

chitters, Child, look at the way they butcher

the fat from the meat. Make a glass talon

of sweet trill and word.

Still, careful, careful.

We both know the dinosaurs

never died, just changed.

I tuck my head into the fault line underneath my neck

where she buried herself,

thank her for showing me when to hiss

or bear my belly like the dead.

Bless her for teaching me

how to turn sweat into milk.

You push your finger into the sand,

say—here is where we will clean the ocean.

Drain all the saltwater from the world,

use its orphaned film to write

our God-given names.

We are like lobsters;

it is right to eat our woman.

It is time to live on the land.

And we will tell you—

you can’t preach the mud off our backs,

turn our truth ugly with beauty and orders.

Can’t sing down our walls of mucus

and you were right,

we are arthropods

but not lobsters to be buttered and boiled.

We are sea scorpions,

making footprints in boulders

making a salvation of carapace

making a god of ourselves

making

the first thing, benthic,

and it was good.

Ashely Adams is a swamp-adjacent writer whose work has appeared in Paper Darts, Fourth River, Permafrost, Apex Magazine, and other places. She is the nonfiction editor of the literary journal Lammergeier. Ask her about the weather.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOWe expected to find it

alone, just us in that sun

under the evergreens

among Zbylitowska Góra’s

enclosed grass plots marked

with names and towns

for Poles, left nameless

Hebrew text for Jews.

Instead, we walked into a forest

of flags growing wild

without roots. Young boys

with Magen Davids draped

heavy, blue stripes over white. Boys

with yarmulkes and prayer shawls

and heads covered and arms wrapped

in each other. So many young boys. A few

older ones. A rabbi. Two boys helping

another walk. A disabled boy. And another one. And then

that singing. Singing

rose like smoke.

Dai dai dai

dai dai dai

dai dai dai dai.

And one of those boys

wailed. Wailed as the rest sang.

Rocked and wailed. And they surrounded

the site

where children

are said

to have been shot.

Nameless and gone. The grass. Wild flowers and bright

butterflies. Neon green and white amid purple blooms.

And the flags.

The singing. The wailing. The rocking. The air

heavy with prayer. And a smaller group of girls.

Shoulder to shoulder, dressed in flags too and some

carrying stones and some one another and most

crying and some just standing.

But that boy’s wail cut

through huddled bodies.

The boy carried by other boys.

The boy who didn’t need

the facts. Who needed

to wail. But we are not

crying or tearing off our clothes

or lighting candles but I wish

we were. Wish I could have joined them.

Sang and swayed and

wailed. Wish that

was what we had come to do. To linger

with the unnamed on their soil. To mourn. But we

came to learn

the facts.

To know that

on the first day 6,000 were shot.

2,000 Poles, 8,000 Jews, and at least

800 children by the end of the second.

That the monument reads

“Polish Citizens”

and forgets

ethnicity.

We came to know

the dates

and times

and numbers.

To listen. But not to wail.

To hear. But not pray. To learn

without feeling.

To look for light

in the break between the trees,

where evergreens turn black

against the high-noon sun

and wailing becomes song

becomes prayer becomes

all that’s left of god.

Julia Kolchinsky Dasbach emigrated from Ukraine as a Jewish refugee when she was six years old. She is the author of three poetry collections: The Many Names for Mother, winner the Wick Poetry Prize (Kent State University Press, 2019); Don’t Touch the Bones (Lost Horse Press, 2020), winner of the 2019 Idaho Poetry Prize; and 40 WEEKS, forthcoming from YesYes Books in 2022. Her recent poems appear in POETRY, American Poetry Review, and The Nation, among others. Julia is the editor of Construction Magazine. She holds an MFA from the University of Oregon and is completing her Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania. She lives in Philly with her two kids, two cats, one dog, and one husband.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOi am going to break my phone

so people can’t hear me but i can still hear them

and i will hear them speak with their eyes closed for the first time

looking needing willing towards a banister in the darkness

a therapy session number passed around south london bathrooms

a contemporary confession booth trapping each insecurity inside a trembling voicemail

your voice cracks your silence dangles

one night i see you eating up breadcrumbs your parents left for you

i join you and we’re doing this together

you’ll say it’s funny how creases in our fingertips tell us who we are

but not how far you can run when your past has a head start

nor the amount of breath you can reach in and steal from someone.

i wrap myself around your waist rest my head to your stomach

to hear what futures you have been swallowing plans fermenting in the last five minutes

the sieve we inherit before i broke my arm balancing on the fence

tyre tracks left a divot in my hands that felt uncomfortable for anyone to hold

the light at the end of the tunnel reaches your face

in the backseat next to mine on the car ride home at 3am

i ask whether you can smell the burning and you kiss me on my temples

to remind me that you know the weakest spots of my skull

Oli Isaac is a multi-disciplinary artist, based in London, who works across poetry and theatre. Their poetry explores the tension of growing up with a speech impediment & trying to access language to navigate their queer and non-binary identity. Oli co-leads Clumsy Bodies, a trans and disabled-led art duo. They are currently part of Soho Theatre’s Writers lab, and are Roundhouse Poetry Collective alum. Author photo by Suzi Corker.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOEnter BB box we requested. Lazy susan chair cover enters. Enter exasperation. Enter things that lie an individual down, on the ground, and have them leaning up against corners. Eyeglasses enter. Attention enter. Judge enter. Teacups enter. Common room enter. Enter black twisted hairs. Enter a cell phone. Enter a ball cap. Enter a phone call. Enter in balmoral. Gravemarker write K.F.B.L.I.O.R. in a book. E.R.K.A.A.D.E.W.O. must be written in the appropriate spaces. Enter visitors. Gravemarker write J.U.L.Y. on a stone. Enter ivy growing where he took his life. Enter the sound of visitors’ footsteps. Reenter into the sound of noises that should still be in your ear because they have been entered and not exited out.

Enter your memory. Enter rememory. Enter air conditioning units. Enter grass in a garden. Enter baby’s breath flowers. Enter John. Enter knowledge that this John is not the same John previously entered though this John is died and gone too. Enter trust. Enter the distinctions comprising a unique name. Enter hence. Enter Martinez. Enter more than enough worthlessness feelings. Enter a different energy. Enter a kitchen table and stuff to sit on the table. Exit a body. Enter a hearse backing up exiting. Enter what seems like a glowing white coffin. Enter cremation. Enter legs crossed but private parts still raped. Enter progeny.

Ovum enter. Enter breeding bucks black. Enter Donnie. Enter new. Enter a colored section. Exit new energy. Enter large male shorts. Neutered cat enter. End enter. In enter. Sight enter. Otherwise of black experiences enter. Enter another coffin. Enter more not guilty verdicts. Enter your own momma’s fears. Enter adaptations to address fear. Enter frfr language. Enter patience. Enter communicative words. Enter workrooms that are hostile. Enter the same suicide thoughts. Enter jailhouse mannerisms. Exit patience. Enter dicks in. Enter the time it takes to endlessly move.

Enter hunger. Enter stomach gurgling. Enter communication. Enter big black dick. Enter unresponsiveness. Enter more worthlessness feelings. Enter words that encourage. Enter your neighbor’s God. Enter one million attempts to feel safe. Enter putting it on your tongue. Enter negotiating for your support. Enter one million attempts to get help. Enter unresponsiveness. Enter worthlessness feelings. Enter suicide ideation. Exit families. Enter a calculator. Enter a Tuesday. Enter the August month. Gravemarker write the numeral 3 on the internet. Enter electronics. Enter the time exact she passed away. Enter accessible doors with handles, without handles, and electric doors. Enter acceptance. Enter tension. Struggle enter. Enter Love. Historicism enter. Enter human conditions. Enter roadside. Gravemarker write L.I.V.E.B.E.T.T.E.R. on a wall. Enter chirping bird sounds out of the corner. Enter music mixing up into chirps. Enter rememory again. Enter your thought. Enter empathy and critical engagement. Enter the seventh month day. Enter time that past quickly. Enter present time. Enter the other John who will get shot and later die.

Remember Angela is written with a surname that is Williams. Remember general. Remember generational designations. Remember John is written with a surname that is Crawford. Enter a supermarket. Enter in seconds. Enter ink. Gravemarker write generational designation (III or the third) on paper behind name John Crawford. Enter garments for attending a funeral. Enter diverse bodies who will celebrate in those clothes. Enter Oh’happyday lyrics. Exit hearses past coffins. Enter gold. Enter desperation. Enter expectation. Exit a crowd pleaser. Enter a good beat tho. Exit families.

Enter blessings. Enter humming. Enter ownership. Enter America. Enter scared to open the door. Enter worship. Enter to walls being built. Move death’s standing next to scared and to. Enter scared to death. Enter intimidation. Enter at work. Exit things that belong to them. Enter more things you personally need. Enter equality. Enter crying. Enter another ask for support. Enter Unresponsiveness. Enter providers. Enter degree credentials. Enter more worthlessness feelings. Enter intimidation. Enter unresponsiveness is typical. Enter great resources.

Enter paper on the floor. Enter what a God can do. Enter a land surrounded by water.

Isolation enter.

Bridge to what is next enter. Enter rivers running deep. Love enter. Enter island. Enter Ti Moune characteristic. Enter preparation for burial.

Enter sea. Enter sheol. Enter fashion. Enter sagging pants. Exit fashion. Enter your rights. Agwé enter. Wrapping waves enter. Enter sweet smelling perfume. Enter time that is closer to an end. Enter cold. Enter fatalities. Enter gravemarker. Enter decomposition process. Enter heat. Enter bed sheets ripped. Enter nightmares. Enter assignments. Enter families. Exit families. Enter the seashore. Enter Papa Ge. Enter debate. Enter risk. Enter love. Enter being carried to shore. Enter psychological distress. Enter suicide in trauma survivorship. Enter being wrapped by waves. Enter a human turned into a tree. Enter recycling. Enter a pact to enter into real love. Enter a noose rope tie. Enter some studies. Enter suggestions. Enter intimidation. Enter a body bag. Enter success. Enter boundaries to it. Borderlines enter. Enter more worthlessness feelings. Enter ignore. Skeletons enter. Enter intimidate. Enter a comment posting. Enter ignorant. Enter physical illness. Closet enter.

Rodney A. Brown is a poet, writer, choreographer, and interdisciplinary artist whose work draws on he(r) experiences with AIDS, mental illness, and homelessness. He(r) writing has appeared in the Journal of Pan African Studies, and their performances on black lives and mental health have been sponsored at the Society of Dance History Scholars Congress on Research in Dance and the United States Conference on AIDS. They taught as a choreographer at the university level and attended the Saint Francis College MFA program in Creative Writing. Rodney recommends the Boris Lawrence Henson Foundation. Author photo by Hubs.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOsidles its way onto my screen. a bomb

has struck a Gazan school, a tangle of limbs

untangled. a cookout of cousins, their breaths

taken for granted, then un-granted, taken.

at the walgreens on the corner of 44th & Indian school

(a street named for the phoenix Indian school,

where indigenous children were forcibly taken, stripped

of their culture, their gutted histories baked

into this asphalt on which my car rests, on which my feet

spring, and my feet carry with them a history

steeped in theft, in forcibly taken, in prisons,

displacement) i taste blood familiar

as sea-stink on the breeze. o

may i note the streets i walk on,

may i sing their massacres, may i bring my own

to meet them. and, now, another of my own

has leapt onto my phone screen

on this street, at this walgreens,

where i have stopped to purchase beard oil.

the redbox outside offers asylum

to a movie where a white man shoots a gun,

a woman pilots a drone, two tongues

tangle together. o

i deem our imaginations complicit. the sun

is warming my skin: were i a patch of grass, i might be

browned beyond repair. were i a troop of fog,

i’d drift and smother the lenses of every cell phone. o

i am too human for all my metaphors, bridges

i am too much body & too much america

to cross. instead, i lean against the friendly wall.

light my cigarette, suck down smoke to fog

my only lungs. i roll the windows up & dribble

beard oil into my palm, crane my neck godwards

to see inside my mirror, & rub.

greet my cheeks with the tips of my fingers,

gentle as a father wiping soot from

a baby’s neck. o my lungs

tiptoe towards collapse, o

i deem my imagination complicit:

may my poems nibble at the mortar in our walls.

i deem my language colonized:

may i find a way to sing death hard & strong.

i massage my chin into submission. o

skin of my father’s mother, o dear colonized

mystery, o hands of prayer, of eating rice

pudding, of holding other hands,

of holding my phone & clutching

tight, fast, insisting on my anti-forgetting,

o thirsty, yearning, thirsty skin, o my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people,

my people, my people, my people, my people, o

may i never find a quiet moment.

may everything echo with each of your names,

may i find you in every hair, in every parking lot,

on every corner of land someone pretends to own,

in the boundless confines of every smoky breath.

Fargo Tbakhi (he/him) is a queer Palestinian-american performance artist from Phoenix, Arizona. He is the winner of the 2018 Ghassan Kanafani Resistance Arts Scholarship, a Pushcart nominee, and a 2020 Desert Nights, Rising Stars fellow. His work is published in the Shallow Ends, Gay Magazine, Foglifter, Mizna, Cosmonauts Avenue, Glass: a Journal of Poetry, Peach Mag, and elsewhere. He tweets @YouKnowFargo and probably wants to hold your hand.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIO1.

Not for the first time, limbs loosen into slingshot. Meaning blurs becomes reckless hum disguised as courage. Too much champagne sparkle, glitterglitzed like jeweled bits of a bottle broken last night while dancing, spilled in the afternoon. Later, I trace the dirt abacus + a boy unstitches the drunk regret buried in my spine. I mimic the pastoral aubade, sob for morning’s sharp sudden light. I am nothing but animal sounds, desperate whetstone scrape + joltblue praisesong. Birdchild crumpled in the grass. Body an archive for the small broken + alive. Soft touch becomes electric when boozebleared, like a dark bedroom bled of lust. A mouse scurries across the floor, finds refuge in the trampling feet of dancing boys, who still each other’s quaking with touch, nostalgic for the next moment alive. In a small house, I cannot feel anything, like my spine’s become a snake’s coil, like my wretched mouth has finally emptied of words.

2.

Not for the first time, limbs loosen into slingshot. Meaning blurs becomes reckless hum disguised as courage. Too much champagne sparkle, glitter-glitzed like jeweled bits of a bottle broken last night while dancing, spilled in the afternoon. Later, I trace the dirt abacus + a boy unstitches the drunk regret buried in my spine. I mimic the pastoral aubade, sob for morning’s sharp sudden light. I am nothing but animal sounds, desperate whetstone scrape + joltblue praisesong. Bird-child crumpled in the grass. Body an archive for the small broken + alive. Soft touch becomes electric when booze-bleared, like a dark bedroom bled of lust. A mouse scurries across the floor, finds refuge in the trampling feet of dancing boys, who still each other’s quaking with touch, nostalgic for the next moment alive. In a small house, I cannot feel anything, like my spine’s become a snake’s coil, like my wretched mouth has finally emptied of words.

3.

Not for the first time, limbs loosen into slingshot. Meaning blurs becomes reckless hum disguised as courage. Too much champagne sparkle, glitter-glitzed like jeweled bits of a bottle broken last night while dancing, spilled in the afternoon. Later, I trace the dirt abacus + a boy unstitches the drunk regret buried in my spine. I mimic the pastoral aubade, sob for morning’s sharp sudden light. I am nothing but animal sounds, desperate whetstone scrape + joltblue praisesong. Bird-child crumpled in the grass. Body an archive for the small broken + alive. Soft touch becomes electric when booze-bleared, like a dark bedroom bled of lust. A mouse scurries across the floor, finds refuge in the trampling feet of dancing boys, who still each other’s quaking with touch, nostalgic for the next moment alive. In a small house, I cannot feel anything, like my spine’s become a snake’s coil, like my wretched mouth has finally emptied of words.

a bee lands on the windowsill,

lazy stumbles into the bedroom where we sleep.

i allow the bee to land on my nose

as if i have never heard of stingers.

i flip over, grasp the cell phone resting

on the desk with someone else’s

severed hand. my mouth slobbers honey & you

wake with a throat swarming

with wasps.

it is possible, yes, the minerals in the cell phone

were harvested from a starved earth

by hands scarred by conflict.

& yet when i wake to tweet

a photo of a dog dressed as a lobster,

i do not think about this.

every day you mourn

tame as a forgotten anarchy

the sin gargled tequila-pungent.

it is possible, yes,

every joy is honey & blood.

i pick up the phone, thumbs-up

a meme. laugh react without laughing.

& a mother collapses at the border of town, her child

plucked from her hands.

the child, in a basement,

loses his first tooth.

the dirt will crack & swallow us

but only through small violences,

like slapping a mosquito mid-bloodsnack

leaving behind the messy remnant smear on your bare thigh.

what an inconvenience to consider its minor life,

to scrape its guts from skin, to return

to mundanity & forget.

i trace the warmth of you,

happy to live here, here

where honey is abundant.

this is a hard grace,

how we forget so easily the origin of salt in the human body,

how the sun rises quick & brings with it a red, red sky,

the horizon splitting open gorgeous like a knifed neck.

there’s a brief barter with each bottle,

a simple equation tilting toward vice.

choose joy, the unwarm neck

begging for a mouth. choose

tonight, tomorrow a slot machine promising

only uncertainty. it is good to feel good,

indulge in a moment’s mercurial luminescence.

even the cancer ward does not ruin

your taste for cigarettes.

even your father’s surgery does not discourage

your sugar feast.

as your body pulses in revolt, you push

another pill past cobblestone teeth.

at your aunt’s funeral, her mother

buries the body in the backyard.

her brother-in-law has crafted

the casket himself.

red faces hover, a grief mob

carrying torches wicked with whiskey.

the drink killed her, they whisper,

this woman who bloomed alive

when blood-monstered,

wedding dance dust storm,

loud-laughed patron saint of pleasure.

graveside, you teeter

tipsy.

flask holstered to hip.

wear a habit. pray

to what cannot save you.

learn first booze-loosed lucidity.

here, see clearly how joy

frays, how an overflowing cup can drown.

behind the barn, choose yourself again.

let the gutwarm lick your brainstem.

call this self care, how you barter

for another moment underwater, then

join the mourners.

take turns tossing handfuls of dirt.

Derek Berry is the author of the novel “Heathens & Liars of Lickskillet County” & the forthcoming poetry chapbook “Glitter Husk.” They are the recipient of the Emrys Poetry Prize & Broad River Prize for Prose, among other honors. Their recent work has appeared in Yemassee, Beloit Poetry Journal, Raleigh Review, Gigantic Sequins, Taco Bell Quarterly, & elsewhere. They live in Aiken, South Carolina, where they teach creative writing to children & work in Cold War historic archives. Their work can be found at derekberrywriter.com

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIOWithout having to lose their tongues to gravity

in a pond of brown water, I see them wash mounds of earth

until they found Coltan. In the beginning was a pond,

shallow—but it would be enough for baptism.

their legs ankle-deep in mud,

this is how they build a dam to keep their homes from burning,

but end up breeding mosquitoes in the water.

our homes are rings of minerals,

we become what we walk upon. so everything ends where it begins,

mama had been sick for months,

but she complains the flowers in her body are dying without the sun.

anytime she sleeps with the lights on, she wakes up with smiles on her lips.

I am my mother with no flower to remediate the pains of losing her lovers to the war.

mama begged that I don’t dig deeper than my knee,

she tells me stories about her childhood,

when the only time she dug the ground was to bury kernelled seeds of sunflowers.

there are a thousand ways to make fire, because the sea is receding

back into its skeleton—each day, it becomes farther from us.

how often do you dream of home when it begins to burn?

we supplicate to the sun to dry out our skin until it turns fireproof.

the branches of what grows on the train tracks when it rains

are curved arrowheads—shaped like cactuses. it colors are the remains

of the blood that stains the ground before the rains.

I was born few days before a giant fire in Kaduna,

it is safe to say I was bred for falconry; we are always ready for flight.

in the direction of gabas, we journeyed until we find other tourists.

the train station is a purgatory of hope, we come here often

to tell ourselves of what we missed about our countries.

the cemetery and the train station have this in common; both have the incisions of the past

that refused our memory a flicker of solitude.

we left home in search of a name and became tourists of borders,

no matter how unsafe home is, I won’t identify as an alien.

Hussain Ahmed is a Nigerian writer and environmentalist. His poems are featured or forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, Poetry, The Cincinnati Review, Poet Lore, The Rumpus, and elsewhere.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE BACK TO FOLIO

BACK TO FOLIO