Unholy Things

The first time I kissed a girl, it was nothing phenomenal. It was easy, as easy as breathing. It did not feel like something that needed to be learned. I was not experimenting or practicing how to kiss boys. I was a 10 year-old who liked another 10 year-old, and the movies had said that when you like someone you kiss them. So I did. She kissed me back. Then her mom walked in.

Her mom was a Deeper Life devotee who thought the only reason I followed them to church was because I was largely interested in God. Of course, I was interested in God. I was interested in finding out why God had seemingly taken the high road of silence, instead of helping me. My cousin, who used to wake up to pray at 3am every day, had been raping me. I was interested in finding out why God seemed to be listening only to my cousin, because what else was he praying for, if not the right to rape a child and get away with it?

However, my interest in God was not the only reason I went to church. It was her, my childhood neighbor. I liked her so much that I wanted to be around her. So, I followed her family to church, and her mom approved of our friendship. This was until I earned her disapproval when she caught me locking lips with her daughter. This was the first time I was told my desires were unnatural. Her mom scolded me for these desires and I was banned from being alone with her daughter. My mom never brought it up. No one in my family scolded me for it. I soon forgot that there was supposedly something wrong with my affections. I would not discover that my existence as a girl in love with other girls was an abomination in the eyes of those who have proclaimed themselves the S.I Unit of Righteousness, until I turned 14 and went to a Christian boarding school in Calabar.

The school had stringent rules for “lesbianism and sodomy”. If they found out that you had engaged in any acts that were considered homosexual, you were faced with a whipping from the boarding house mistress, and public ridicule. In that school, even the most intimate things you said to a counselor would end up as common knowledge in the hostels by the end of the week, and you could be expelled if they felt you were irredeemable. I learnt to hide that I liked girls. Thankfully, I had bigger issues. A boy had lied that we’d had sex. The news spread like wildfire and I became the school’s boy-crazed slut. At the same time, I began to pray the gay away. I started out thinking this was possible because the preachers at school said God could do all things. I forced myself not to question why God could not save me from sexual abuse but could save me from being gay. I was desperate. I began to think that just maybe my punishment for being gay was sexual abuse.

I declared myself an atheist about the same time I discovered that I was also attracted to men. I was 18, and for some reason, my body decided that it would find a man’s touch less repulsive than usual. I was also tired of praying and trying to fit into heterosexuality because all the churches I had tried had labeled my affections impure. However, I was by no means done with belief, or the church, for that matter. In my early twenties, I returned to church. I figured my attraction to men meant I could still have affections towards women but

only date men. I would no longer be committing a sin.

The day I discovered arsenokoitai,¹ I was overjoyed. The possibility that the Bible was not exactly against homosexuality flooded my being with so much light as it provided me an opportunity to have faith and still be queer. I was already in the process of forming new opinions of God, deconstructing my faith and building new beliefs. For example, I no longer saw the Bible as the word of God. I saw it as an evolution of man’s understanding of God, which could be colored by all kinds of personal bias. Discovering that arsenokoitai, the word which had been translated to mean homosexuality, was referring more to pedophilia, and that it really meant “men lying with boys,” helped me find peace in my sexuality. Discovering that arsenokoitai was not translated to mean homosexuality until sometime in the 1940s made it easier for me to practice my faith and still be queer.

I had finally found peace.

But my mind and body had other plans.

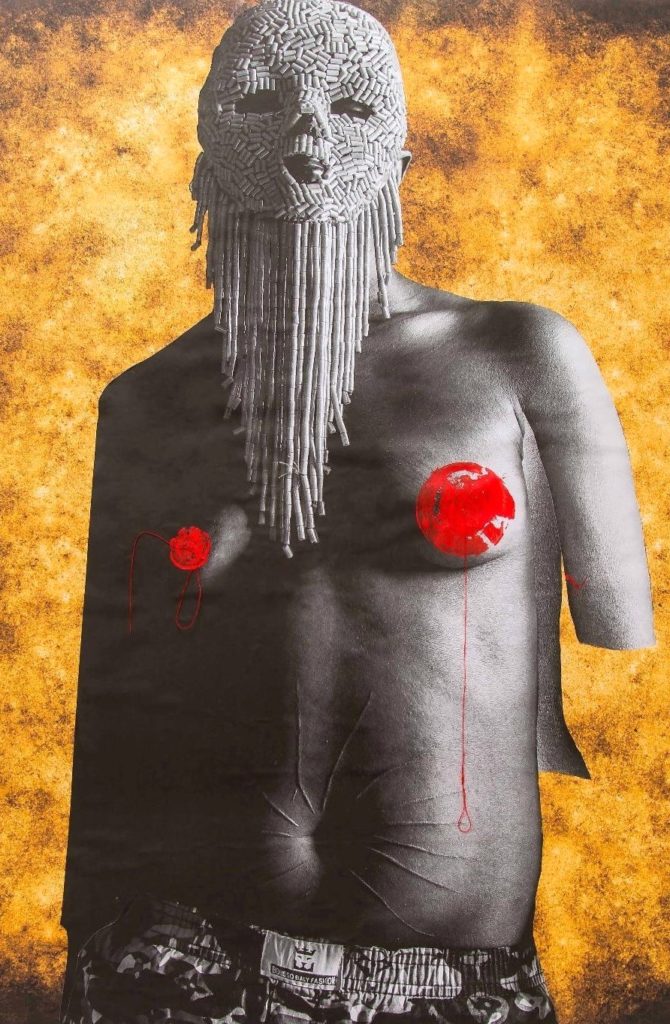

I have always felt like I was born in the wrong body; a body that learnt to grow breasts at 10, round hips by 14, a body that is curved in ways that have made me want to end myself. However, the urge to bend this body to fit my spirit had not been so intense until I turned 23 and began to feel like if I did not do what had to be done, I would un-alive myself. I filed this under the category of “one of the quirks of my mental illness.” Every Christian I spoke to told me to pray harder for myself, to focus on Jesus, and to watch the content I consumed because, to them, gender dysphoria is a disease which is transferable via social media content. Suicidal thoughts and attempts became old friends, easily accessible through my jar of pills.

This was the turning point for me. All my life, I had felt like an unholy thing, like my queerness was a stubborn stain that required the most extreme methods to wipe—even if those methods required ending my connection to this mortal world. I knew I could not go on like this.

First, I made peace with losing my faith. Faith is meaningless to the dead. Second, I took out time to make sense of the gender dysphoria I felt, to explore what it means to not feel at home inside my body, and to begin the journey to making this body the home it was meant to be for me. I had to come alive to Self.

I was born into this world with no manual for queerness. Nobody prepared me for the reality that I would become a social misfit in the country I call home. Nobody told me that I would fall in love with the wrong gender. Nobody told me that I would struggle with self identity on some days. Nobody prepared me for the loss; the loss of a faith I fought so hard to keep, the loss of community that came not only with being queer, but being open, too, about seeking ways to make this human vessel conform to what being queer means for the spirit that lives within it. Nobody told me how painful it would feel to be labeled unholy, when all my life I have worked to be good enough, holy enough. Nobody told me how difficult it is to build new beliefs, to find a different faith, to embrace myself as god, to accept that I have always been holy.

¹ Arsenokoitai — an ambiguous, unusual Greek word used in letters by the biblical Apostle Paul. It was translated into the English as “homosexuals,” even though no such word exists in either the Greek or the Hebrew. Some scholars posit the Greek “arsenokoitai” might more specifically refer to pedophiles, pederasts, and/or older men who solicited sexual relations with catamites.

Chinwendu Nwangwa is a Nigerian multidisciplinary artist and an academic currently fascinated by linguistic anthropology and its use as a tool for social development. She spends her time between Calabar and Lagos where she hosts friends and loved ones to delicious, sometimes experimental meals, and runs one of Lagos city’s reputable book clubs.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE