I would rather wear a dress than have a body. A good dress defers wrinkles and sagging, refutes deformity. I substitute my childhood body with my first dress, gray cotton printed with pearl-pink pansies. My arms become the arms of the dress, fabric tight above the elbows, ruffled with machine lace. When I grow out of it, that dress becomes my sister’s, and I lose the shape of myself.

I had other dresses, though, and other bodies. The homemade royal blue taffeta with raw seams beneath, puffy Princess Diana sleeves, and a bertha of translucent ivory lace. I spun in it, skimming the tiled floor before falling in a mushroom circle of blue fabric, more buoyant than my legs would ever permit me to be.

The thin-striped plaid I wore in fifth grade, the last time my body was undifferentiated, mostly unsexed. The dresses I wanted and could not possess: my mother’s pleated pale green polyester dress, last worn for her wedding reception. My great-aunt’s spangled evening gown slowly disintegrating from exposure to air and sunlight, but that made my wrists shimmer in jet.

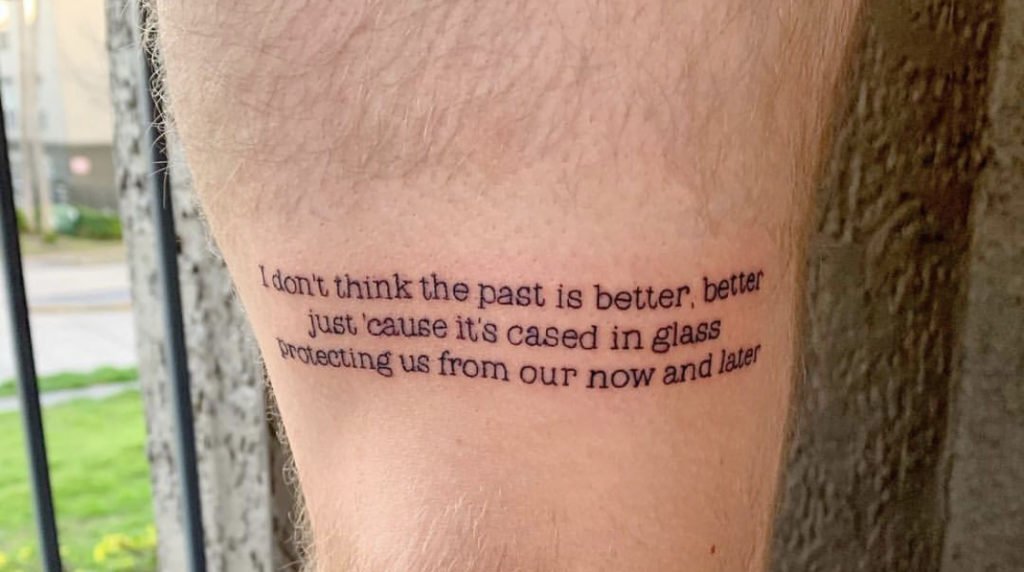

Dress was the closest I had to religion. I read about their powers in the lavish details of my books. The clothes were stories buried inside stories: apple-green net, Cluny lace, organdie, rose petal silk, cut velvet. Brown cambric, a flounce of poplin, bound in a band of plain brown silk. I learned that sometimes the loss of a dress was a portent of another loss, the moment in which scissors snipped or buttons popped, and left nothing but the shivering animal of the body beneath. The orphan girl, bereft of fur wraps and white frocks, left alone in a black crepe dress.

I tried to learn to dress myself like these women did; I searched clothing catalogues, circling favorite outfits, and tried to remember precise combinations of color. Soft Orchid or Bright Pink? Watermelon Sorbet or Poppy Blue? The names were seductive. But mostly the clothes I wore refused to reshape me. When I sat on the toilet, the flesh on my thighs puffed out like small pillows. No one I knew had calves as round and full as mine.

I wanted to live inside bodies like the ones of the other girls in my fifth grade class, girls whose legs were slender and lovely, their hands thin, their feet narrow. I covered my body in t-shirts, a pair of knee-length kelly green shorts; my feet could only fit in boy’s sneakers, utilitarian and primary-colored.

I understood, in some small and unarticulated way, Judith Butler’s musings on identity. The women who dressed in my books glimpsed, as Butler did, how gender came to be. It rose past the body and into the dress, into the graceful pageant wave, into the way I learned to modulate my steps. Women put on a work dress and their selves deflated, condensed to a single task. But when they entered the world, they slid pearl necklaces over their heads, fastened the strings of violet silk, and assumed their becoming. To get dressed was to carve out a space in which they could exist. I tried to costume myself in the same way. “It’s the dress, dear,” I said, echoing my books to my reflection. I draped my arms in my mother’s clothing, turning my shoulder to admire the fall of a painted silk scarf down my back, clamping her clip-on tortoise earrings to my tender ears. “Fine feathers.”

Dress softened the treachery of my body’s development. Small dark hairs, unerringly visible, cloaked my limbs. I wore jeans and long sleeves in the humid heat of the summer, refusing shorts until I finally picked up my father’s razor and began to shave. I wore a skirt that afternoon to the dentist, where, splayed in the chair, lines of dried blood appeared under the clinical lights. I could either bleed or be shrouded. Dress became a way to negotiate with that world.

I shamefully wore a C-cup bra in eighth grade, DD in tenth, and continued to inch up the alphabet. My breasts felt cartoonishly sexual in the model of Jessica Rabbit, who cooed voluptuously on screen as if her words in themselves were curved (She fascinated me, the way her glittering sheath clung to her body and then fell away). Boys, some far more slim and elegant than my early-woman body, avoided me. When a friend fell asleep with her head on my shoulder, I heard the word lesbian giggled through the bus.

I tried not to look at my body in the bath, and instead slid it under a white soapy film. I told my mother, whose body resembled mine, that I wanted minimizers. Anything to flatten the flesh and make it less obtrusive, less obvious.

My gender is wholly feminine. I like the word femme for it, which indicates a conscious femininity performed not to attract masculine desire, but with queer longing in mind. But my body has never permitted ambivalence. In my high school’s performance of Guys and Dolls, I was given a men’s suit in delicate stripes of pastel yellow and blue. I did not look like a man, even with my face scrubbed and hair pulled tight against my hairline, flattened with a wide Ace bandage. I didn’t know then that this is something many trans men try when first attempting transitioning, and that the bandage’s tendency to contract when the rib cage expands can injure breast tissue and fracture the ribs. I could bear it for an hour, and then, standing in the stall, would remove my shirt and unravel myself breath by breath. My flesh softened the crisp lines of jacket and sleeve, swelled at the trouser seams, and failed to disguise.

Of course, men have not always worn pants. I show my students a sketch of Ancient Greece’s thigh-high dresses and laced gladiator sandals. They laugh, palpably embarrassed by the sight of a masculine body tainted by femininity. But a dress is utilitarian.

In class, we look at men’s calf shapers, corsets, and how men historically have padded their hips and chests. Beau Brummel, who needed a valet to pull the close-cleaving jacket over his shoulders. Oscar Wilde wearing silk-trimmed velvet waistcoats below the intricate knots of his ties. Kings donned protruding ivory codpieces, stark white hose that revealed a man’s well-turned calves, and lavender court suits embroidered with pink and violet cowslips.

We wear clothes to establish gender, or to refute it. This is a balance that queer women, in particular, have to navigate. I do not dress like a straight person’s idea of a queer woman; I do not dress how many other queer women think I should.

The first time I attended a campus support group for gay and lesbian students, I wore a shirt that flared canary yellow, an alarm of uncertainty about my orientation. It was worse than feminine, little girl cute: Swiss dot cotton, Peter Pan collar, puffed sleeves, buttons covered in fabric.

Toward the end of the meeting, a student across from me rose and centered her fist in her palm. We need to be visible, she said. Shave our heads, she continued, seeming to speak to me directly. Wear shirts that declare our difference (she was wearing a tank top that my mind refused to call anything but a wifebeater). We should reject bras and never wear dresses.

I believed in the same things that she did, to some extent. That normalcy and invisibility were antithetical to liberation. But what she advocated for was a misunderstanding of dress, assuming that it could supplant other aspects of identity. Dress is performance in many ways: prom and theatre. But what Judith Butler and any actor understands, is that the assumption of a costume is not enough to create any kind of role.

Still, it helps. There are certain clothes that I wear only to teach. My wife and I refer to these as “teacher drag,” because they have a certain stagy quality to them: a brown sweater vest, a navy blazer, a burgundy turtleneck. I wear these things in part because I am performing confidence and intellectualism, much as an actress who puts on a pair of glasses in a film is performing undesireability. I must be the teacher, dressed like that. It is my way of negotiating the world, of shaping expectations before I even speak.

This is the real purpose of dressing for the occasion: not just social norms, but a way of negotiating with the world’s perception. I weigh a little more, or about the same, as the average American woman. I veer on plus-sized but am what is called a “small fat,” a woman who can sometimes wear straight sizes but sometimes settles gratefully into a 1X or 2X. Denim marks me with a series of dappled pink marks, and tights make a riotous ring of scratches at the softest part of my belly. Bras leave welts on my back and wounds on my side. But a pair of leggings or a loose-cut shirt looks sloppy on me, as they rarely do on thinner bodies. Dressing nicely (in ways that read as feminine, as safely middle-class, as attractive and clean) asks people to treat my body well.

These associations have long been present in the Western world, but in the past hundred years there’s been a slow movement, shifting the locus of control from outside the body to inside it. The corset, the waist trainer, the girdle, have been replaced with athleisure that puts the body’s self-denial and discipline on display. Advertisements celebrate women’s liberation into yoga pants. We are free now from dress and underpinnings, corset and crinoline. So goes our cultural narrative. Asterisk: assuming said body is thin enough, white enough, young enough, able enough.

My favorite brand of jeans promises that I will “look, feel, and wear a size smaller” through their ability to flatten, contour, slim, shape, or lift. They displace and smooth fat at the hips, the accumulation of skin at the waist, just as corsets did, to “permanently reduce and improve the figure.” That bodies can disappear inside clothes is the fiction we love. It’s the reason fashion designers cast models who they deem can act as living hangers. Their bodies are invisible, weightless, the inverse of the emperor with no clothes. The dress with no woman inside of it. That these women are malnourished, underweight, smoking cigarettes and liquid fasting backstage is beside the point. These models breathe silk, they move and a gown moves with them. Most couture is meant for them alone. Their extraordinary bodies, beaded and caped and fluttering, present vitality. They argue for beauty.

Part of me wishes we’d return to clothing that lies more honestly about the body. We’re all in on the joke; nobody’s waist looks like that, so everyone’s does. The optical illusion of an hourglass for a medieval woman’s ensemble mattered more than her actual shape. The bottom half relied on a farthingale—an early hooped petticoat padded with thick rolls of muslin—that grew like a layer cake, the waist shrinking in an optical illusion. Up top, the bodice was compressed into one long conical shape, breasts flattened, waist elongated. They called their proto-corsets bodies. The richer a woman was, the more ostentatious the fabric of her body. Henry VIII’s queens ordered ones stitched from crimson satin, cloth of silver, sweet leather, black velvet, and French damask. Their household inventories are the closest that historians get to a biography for these women.

I want a biography of dress. The clothing I wore is the evidence that I am willing to give. Not the private writing, full of shame and triviality, but the dresses I’ve compiled to cover my body. The ivory-peach dress with the sleeves that fluttered—you look beautiful, my girlfriend says. The black halter, mostly backless, the velvet ribbon bisecting the nape of my neck. The dresses full of flowers, a garden stretched across my body, abundance and life as my cells weaken and begin to disperse as slowly as they do for a mostly-healthy living being. My clothes keep me together.

I make sense of the world through dress. The progression of time is easy to think of in terms of fashion: there’s some stuttering, some doubling back, but dress lets me see the flickering shape of human desire, pettiness, and love in the muddle of history. The hourglass Elizabethans gave way to seventeenth-century high waists and full skirts, evoking fertility, creating women who could float on the canals of Amsterdam and Venice. Dour Dutch women showed their status by wearing black, a color that soon faded to rusty plum if not maintained. The lace-edged ruffs that trembled at their throats remind me of birds, the human body flaunting its plumage for a possible mate.

I search for a favorite era, a time in which I would have been beautiful, as if I can make some kind of peace with my shape by imagining it elsewhere. But there is never an ideal. There’s only whatever costume people have adopted to convey health and wealth, to model piety or confess to infidelity, to demonstrate sexual longing or signal a political alignment. No one silhouette remains desired for long. Skirts grow longer and wider, then shorter and thinner. Conspicuous consumption led to English court mantuas that could span the width of a contemporary dinner table, and, centuries later, became delicate, kimono-like lace gowns. I admire the relentless absurdity of dress. The robe volante, created around the same time as the Persian-influenced, unisex dressing gown called the banyan, made the women who wore them resemble pregnant triangles. In the 1820’s, dresses were so stuffed with horsehair and gilded with ribbon trimming that the gowns stand, fully embodied on their own.

Clothing today seems flat and mundane in comparison to the dresses trimmed with woven silk braid, hand-pleated ribbons that remind me of Christmas candy; tambour beading, which requires an artist to bead by feel and not sight; Brussels lace and bizarre silks. The dresses that remain intact in museums, even faded and preserved, are more vivid than something I could buy in a store. Even the backs of a these dresses are be pin-tucked or flounced, cascading or bustled, hours lavished on something that the wearer might never see.

The clothes today, conversely, are often designed for the selfie. These dresses are intended to be seen fixed from overhead, or draped and pinned around blank mannequin’s form. But they are clothes that are also meant for the coffin, the only time we are truly formed and fixed. My cousin’s body, cloaked in the religious garb of white blouse and vivid green silk skirt was meant to signal her ascendency into heaven, but served practically to conceal the abrasions and broken bones, the burst blood vessels, the bruising from where a SUV had crossed a lane and overtaken her bicycle. The clothes held off, for just a moment longer, the reminder of her body. They offered the illusion that she might carelessly stretch her mouth back to life and lift her head.

In the nineteenth-century, mourning rituals helped shape grief in another way by prescribing what kind of clothes a person might wear after a death, and how long their sadness was meant to last. First cousins require four weeks of mourning; aunts and uncles, two months. Widowed wives, being the most bereaved, mourn for a full two years. There’s something I find attractive about permission to mourn so visibly, to let body occupy the space of grief in paramatta silk or bombazine. Mourning fabric was black fabric, chosen because it absorbed and did not reflect the light.

But any dress today could be suitable for mourning. Every piece of clothing I own has an innocuous tag that tells the story: made in India. Made in Burma. Taiwan. China. Bangladesh. Western fashion has been stealing from these countries for centuries—it used to be that we were manic for paisley shawls, sari striped silk, and bolts of printed muslin. Kashmiri shawls were first coveted, then copied to the extent that demand rose for the knock-offs alone. Now we’ve taken enough designs, enough sacred heritage for patterns, we simply go overseas to have our clothes sewn.

If I tried to trace the supply line of my favorite dress, reaching back from shop to stitcher to cutter to draper, back to weaver and dyer, I wouldn’t be able to. Companies escape anti-slavery laws by subcontracting unto subcontracts, deniability rooted in unknowing. Clothes that I wore in the mid-nineties, purchased at Macy’s, might have been sewn by one of seventy-two Thai slave workers who lived in a chain of California duplexes ringed with barbed wire. Chances are even better that my first bra was sewn by a woman in a South Carolina prison, paid thirty-five cents an hour to slip elastic inside machine-sewn lace.

This history doesn’t change. In 2012, one hundred and one years after the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, the Tazreen Fashion Factory burns down in Bangladesh, killing at least 117 people. The fireproof tags meant for the clothes are discovered later, bearing names of Walmart, Carrefour, and IKEA. Even if I don’t wear these clothes, I am still culpable, I am helpless before the specter of these ruined bodies. Helpless is a wealthy woman’s word, evoking the deliberate choice to be in despair, like the anorexic models who strip themselves of their nourishing fat. But also the bodies of the women in Cambodian garment factories too, who have begun to faint in waves, falling prone to the floor one after another until they carpet the factory. Foreign journalists photograph them sprawled on the ground. Mass hysteria, remarks a Cambodian newspaper. Then, they too draw a line between past and present. Not unlike English workers centuries ago.

Exploitation is just on a different scale now, in a different country. Embroiderers in the nineteenth-century stitched bone-white flowers onto white tea gowns while they crouched in their tenement homes, hands gloved to prevent smudging. Children now and then, employed to creep under humming machines, could slip a hand in the wrong place and have it ground to bone and blood. The best ornamentation has always come from ceaseless human labor. Embroidery machines can’t replace the calluses and needled wounds. The patterns produced from a computer are embarrassingly crude, wide tulips in the place of tiny repeated flowers.

The only solution I can find is to raise my own sheep, shear my own wool, to card and loom, to dye, to stitch and scissor. But better still to stop caring, to transgress without pleasure. The ancient accusation of vanity appears, this time cloaked in different rhetoric: dress is frivolous, a waste of time and good material. I’m betraying the sisterhood by being one of those women who love clothes and jewelry. Misguided at best, actively anti-feminist at worst. “A woman’s clothes,” declares the advertisement that I continually see online, “should be the least interesting thing about her.”

But to ignore the importance of dress seems another false choice, a willful misunderstanding of its potency and power. In the days of Stonewall, queer men and women slipped into clothes that made them feel beautiful. Panties sheer and filmy with lace, tiny rhinestone buckles, military jackets with their brass buttons. Leather jackets, neckties, iron-pleated plaid skirts. Things they could breathe freely inside. If they were discovered in a single article of another sex’s clothing, went the rule, meant that the police could arrest them for deviance. For some trans women, the act of wearing a dress is a revolution, a declaration that I am who I am. When I am twenty, cashiering at a grocery store in central Utah, a woman shops every Wednesday in bright dresses made of delicately layered silk, flutters of tangerine, butter-yellow, periwinkle, or rose madder. I watch people stare at her jaw line while she pauses to pluck a red cabbage from the crate.

Who gets to wear a dress, what dress, and how? The fashionable way to wipe out indigenous women’s bodies was to first force them into colonial garb and then to appropriate their designs and silhouettes. Domestic servants in colonial India wore corsets while England shuttled sari silk for their own designs. Pocahontas, painted in an Elizabethan ruff and pearls, with wisps of black hair escaping her coif, has the steadied and silent gaze of a woman who understood this.

I run my hands over the dresses in my closet, as if to feel all the bodies that were needed to create these ghosts. The hundred dollar pale blue silk dress, with its lace inset to cover the collarbone, fastened up to the hollow of my throat, seems to heat under my fingers, same as the boiling water that killed the thousands of silkworms that spun the material. My favorite shirtdress, printed in concentric circles of fall colors: orange, yellow, maroon, and brown. Made in Bangladesh. The dress that my mother sewed out of pure love, fitting green taffeta onto my sixteen-year-old body, standing with me on Sundays to choose the right silver buttons and silk cording, reminds me of the slash the scissors made on her palm. Other dresses grow heavy with the memory folded in the skirts. My faded cotton sundress I can’t bring myself to throw out, Prussian blue printed with white bicycles, worn the summer I learned letterpress printing.

This is another lure to dress. Retail fashion understands this. Buy new clothes and receive a new self. Defend yourself against aging, against sagging, against the inevitable losses and gains of the body. I craved saddle shoes in fifth grade, imagining that I would transform the moment I slipped them onto my too-wide feet. When I married another woman, I chose a froth of French lace and Italian cotton tulle, a piece of lace from my great-grandmother’s gown sewn onto the bodice. I wanted legitimacy from this dress. The court ruling permitting us was tender and new. Clothing was a talisman again, a way to preserve and to guard.

But the trouble is that these identities are as easily shed as they are acquired. Americans discard nearly 82 pounds of clothing, per person, per year, to the total of thirteen million tons. So far this year I have rid myself of an old pink cashmere scarf, a striped sweater dress, a black sheath dress, and a white and black wool skirt. A vibrant green blouse with scalloped sleeves, four pairs of jeans, two pairs of shorts, a purple sweater interwoven with silver threads, four sagging bras, and a grocery bag of unmatched socks and torn underwear. Most of it, I know, will end in a landfill. Some of it may be shipped to other countries under the guise of charity, cheap American denim and Disney knockoff shirts flooding local textile markets.

In the past, holes were patched, fabric re-dyed, hems turned over. Clothes were patched into quilts, braided into rugs, folded into a doll or a bandage. But the things we wear today are cheaply made and frequently synthetic. My favorite pink cardigan splits first at the neck seam, and then, improbably, in the middle of the sleeve.

I try to save things from the wrack and ruin of the landfill, but all I’ve created is a living mausoleum that swells inside my closet. Things that no longer fit, are faded and thin, or pilled and stained. Most are hidden inside cardboard boxes, but my wedding dress is on display, visible through the plastic window of the box. It stares without seeing, torso deflated and disembodied. The preservation service (what had I imagined) meant that the dress arrived embalmed, pristine in an acid-free tissue wrapping. My wife’s dress rests next to it, in its own box. Dress sits by dress, coffin someday by coffin.

But sometimes our dresses outlive our skin. Bodies preserved in bogs have been discovered still wearing woolen skirts and sheepskin cloaks, the clothes preserved well enough to cut a pattern from. Egyptian beaded dresses are lifted from bandaged corpses and stolen away to Western museums, where they hang off cloth torsos, permitting visitors to imagine the body within. Mummified Dutch women surrender their caps and gloves to archeologists, leaving their bare skulls and leathered hands exposed. Air-conditioned boxes contain mourning shoes and wedding gowns of famous women. Walking through a fashion museum, I catch sight of Queen Victoria’s fat birdlike figure, flickering through the shape of her black silk gown. Our clothes offer a gasp of immortality: a remembrance of the space our bodies occupied, the genders we assume and are assigned, and the endless performances we gave. I tell my wife to wear Italian mourning garb to my funeral: an expensive black lace dress, a heavy widow’s veil, a felt hat tilted rakishly over her forehead.

After I die, an enterprising mortician might slit one of my dresses open in the back and arrange it around my body. Bury me in pansy cotton, blue taffeta, my French lace. Drape me in butterfly linen or black velvet, cut to expose and not conceal. Just remove a few bones, drain the blood, or cut out an organ or two. Anything, in death, will fit.

C. A. Schaefer‘s stories and creative nonfiction have appeared in Indiana Review, Mid-American Review, Phantom Drift, Passages North, and elsewhere. A former editor of Quarterly West, she holds a Ph.D. from the University of Utah. She lives in Salt Lake City with her wife and a small menagerie of cats. Read more at caschaeferwrites.com.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE