Manic Panic or (A Micro-Nonfiction About Annie Clark and How She Helped Me Grow)

I almost threw up the first time I internalized St. Vincent’s “The Party.”

It was the first time that music really sounded like poetry to me. I pictured my own relationship fizzling out like a dying candle, having gone stale due to inaction or indifference. Much like St. Vincent’s narrator, we would try to salvage what we had, but alas: The party is over and we both look the fool.

I grew up on dad’s Van Halen and mom’s Garth Brooks – music you can really tap your foot to, sure – but upon discovering the music that spoke to me, I was smitten with a queer woman who stood no taller than 5’7” and could shred on a guitar with more emotion than that of the Pietà.

Under the neon sign of the Continental Club in midtown, I sat on the concrete, tacos in hand, and listened to her myriad catalogue on shuffle. I was working for a now-defunct music festival on their public relations team. If I was to produce content to promote Annie Clark – who would be lighting up one of our stages that year – I had to make sure my angle was perfect. Masseduction had just dropped.

“Who is Johnny,” reporters ask her ad nauseum. He first appeared in the title song of her 2007 debut album Marry Me as a “rock with a heart like a socket I can plug into at will,” and returned in her self-titled project in the track “Prince Johnny,” a person of interest to her who was lost in a downward spiral – as she was, too. “Johnny’s Johnny. Everyone knows a Johnny,” I remember Clark saying in an interview once.

Beneath the neon glow on that midtown sidewalk, somewhere between “Slow Disco” and “Happy Birthday, Johnny,” I remembered the folks in my life that I’ve lost connection to. The manic panic of Masseduction’s wild Holzer-when-not-pastel palette fell away, and while Clark could have been talking about a former lover, a brother, a friend, I thought of my birth mother.

At the time, I didn’t know where she was and the longing to know her was deep and heavy. She had left when I was two, and was in and out of jail thereafter, farther estranged with every passing year. I hadn’t seen her since I was six? Eight? I had a wonderful mother who raised me with my dad, but the woman who birthed me, I couldn’t help but wonderwho she was.

Her favorite song. Her favorite color. If she was still alive?

As Clark crooned, “When you get free, Johnny, I hope you find peace,” I wept into my barbacoa.

I might never get the chance to answer those questions. Despite her flaws and transgressions, she was a human life that I valued for reasons I never learned to articulate. Did I want to know her so that I could infer whether I would parent my own children the way she did (or didn’t)? If my own tendencies were inherited?

When the festival went live that year, St. Vincent was in good company. The lineup was female-led, in which Clark fell in rank with such powerful femmes as Solange, Phantogram, and Pussy Riot. My impossible task became trying not to think about my meds for anxiety, depression, and sleep when she rattled off the lyrics to “Pills.”

This was the first time I’d been confronted with the Masseduction-era aesthetic without the lens of a Spotify album cover. The latex. The thigh-high boots. The blazing red – everywhere – and the dual-tone blues and oranges of the digital art behind her. It was otherworldly. It was mid-modern with healthy deviance. The Holzer influence was back during “Sugarboy,” when Clark promised me that she was a lot like me. Alone like me. The lyrics ticked across the breadth of the stage above her perfectly slicked hair while she and her guitar wailed, and wailed.

I stared up into the white December sky flanking the Houston skyline which sprouted up from all around us. The chill of the air was only interrupted by the backpack of the woman ahead of me. Jumping while we all danced, her backpack jerked me back into reality every time it hit me in the chest. Only when she turned around for a selfie with her squad did I realize it was Pussy Riot themselves. Until I recognized their faces, they had blended in with the other festival attendees; after all, they were without the neon ski caps that I had seen them don earlier in the day, when they’d performed on our largest stage with a banner that screamed, GOODNIGHT WHITE PRIDE.

Who else can say that they danced to “Masseduction” with Nadya Tolokno?

It’s been several years since that day I met Nadya and saw Clark live for the first time. And from the first time I heard her music, nearly a decade had passed.

I was in high school and still toying with the idea of coming out of the closet to my family when I came across her first album. Real recognizes real, or queer recognizes queer, and I was pulled in by the sound of the weird girl who could shred. The weird girl from Texas who sang about the most visceral things and paired it to the most floral music – at the time, a sound that betrayed her look.

In the years since her first release, her style evolved to create the commanding presence she is today. The bite was always there, but it came from a package that appeared meek, not unlike discovering cayenne in a dish you thought you’d clocked. The pretty-vicious of Marry Me and Actor and the avant weight of Strange Mercy could have only led to the larger than life near-future dystopian head of state we heard in St. Vincent.

The parallels of Clark’s evolving queer style and my own aren’t lost on me. As I came into my own, I enjoyed the push of a harder, sleazier aesthetic as she rebranded and took the reins of her career for herself. I was inspired by the power dynamic present in her clothing, makeup, and promos – the clean cuts, the focus looking down on the camera – and hoped I could emulate it as I came into my own in college, despite never seeing this side of my own self before. But if she could do it, why couldn’t I?

By the time Masseduction came out, I was feigning confidence. This album and the leather, latex, and barbed lines it brought with it had me realizing I had fallen in line again with what the work meant to me – sexually confident, uncomfortably nostalgic, and abundantly queer.

Throughout Clark’s career, the laureate lyrics remained while the aesthetic advanced, and I strung along like a dog in tow. Over coffee and over the course of months and years, I studied from an unknowing poet how to turn a phrase and tell a story, while losing my mind with how well the lyrics applied to my own experiences – or how well I could apply them myself.

In “Year of the Tiger” and “Strange Mercy,” I pictured myself as a child, faced with the impossible news that my birth mother was going to jail, prison, rehab, another city. I was never granted the opportunity to talk to my well-meaning – if not entirely misled and hurt – unknown parent through the double-paned glass. For me, the glass was replaced with other family members, the jail swapped out for a holiday gathering. Aunts and uncles were uneasy to discuss her whereabouts because they, too, were hurt by her life. Forever protected from the image of her pale, pocked, and exhausted face under harsh fluorescents, I was left to send messages to her through family who may or may not have answered her collect calls.

After the festival that year, I went home to my studio apartment, less than a mile from the festival site. The 1930s apartment building was a reprieve from the hustle but was not immune to the noise of it. The train, the sirens, and the neighbors reminded me I was not alone in this world, and never would be, but my conscious focus on my brief history, my unrequited exertion to break into the scene as a young writer, and my apartment heater that didn’t work pulled me onto the hardwood floor. Perhaps it was the rhythm of the music or the mania itself, but I played St. Vincent’s catalogue on repeat again, sprawled on the rug with my dog curled into a donut at my side. It was a futile attempt to leverage history with the present through lyrics that weren’t written for me anyway.

Unbeknownst to her and without consent, I had been using Annie Clark as a muse, assigning her very personal lyrics to my own very personal – and vastly different – life. In this time as I flailed about in my unchecked mood swings and longing for a life that I didn’t know (nor did I know I would want should it be granted to me), I had failed to register the hopeful uptick of the final bars of “Smoking Section.”

In predictable fashion, I put the song on repeat. I walked my dog to Hermann Park and back. I was in Houston on those streets, in practice, but certainly not in theory. My mind was everywhere else all at once. Had the drama been real? Or was I still strung out on my own insecurities, the longing to know anything about my birth mother, and the exhausting coming out experience and the years that followed, from being on the brink of poverty to the struggle to find a job?

As much as I wanted to fling myself from the roof of my apartment building like the narrator of “Smoking Section,” I had to believe Clark when she posed, “What could be better than love? It’s not the end.”

It’s not the end.

It’s not the end.

In “I Prefer Your Love,” a tender ballad about a mother’s love – the only St. Vincent song actually about a mother – I thought of the mother who raised me, and not the one who had left. “All the good in me’s because of you,” she whimpers, underscored by a haunting disembodied vocal describing a “little baby on your knees, ‘cause the world has got you down.” I wrestle with the solace that I must feel in that my birth mother left so early on. Because of that, I was raised by a mother who fostered the growth, the writer, and, well, the good, in me. Something the other couldn’t do.

My mom took on a lost feral child. Maybe, if St. Vincent wrote a song about that, I would send it to my mom as an apology for all the years I spent as a lawless youth, a questioning and quiet teen, and eventually, an unapologetically queer adult.

Or, perhaps she did write one and I just haven’t interpreted it that way yet. Give me time.

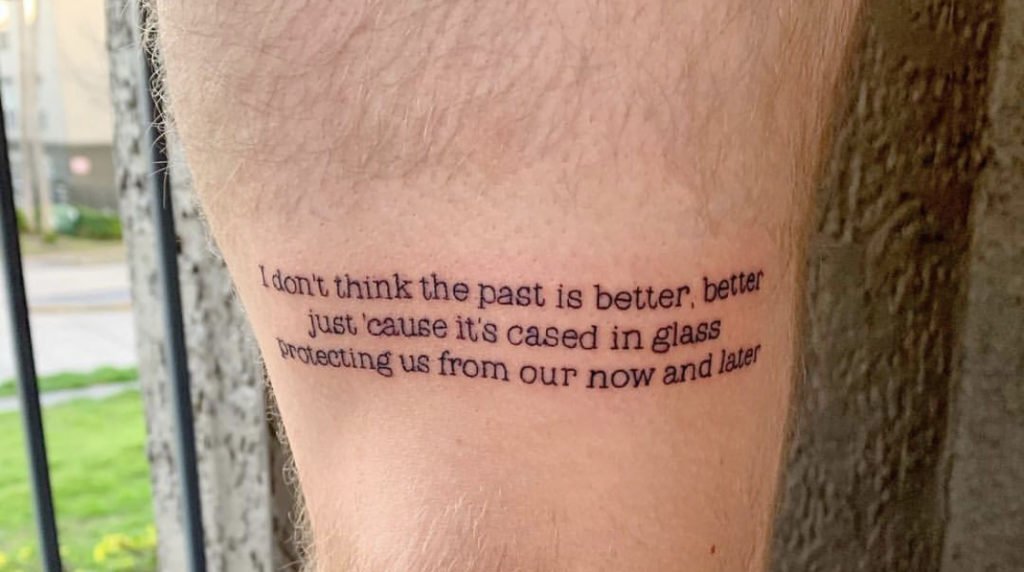

As a hungry 27-year-old in New York City’s East Village, I stepped foot into a tattoo parlor. After about an hour or so, I left with a lifelong marker on my right thigh:

I don’t think the past is better, better

Just ‘cause it’s cased in glass

Protecting us from our now and later

Annie Clark taught me that nostalgia – good or bad – is skewed. Your memory is not in context, and if you aren’t careful, your past will hinder your future if you spend too much time lost in it in the present. I smiled into the white February sky flanking the Manhattan skyline which sprouted up from all around me. The chill of the air interrupted only by the voice of my roommate, grounding me in the present.

Barrett White is a print journalist, editor, and dog person based in Houston. He attended University of Houston in the esteemed Creative Writing program and has spent close to a decade in queer media, lending his voice to both regional and national outlets alike. He is also a co-host on The 2081 Project, a podcast that looks deeply into the issue of LGBTQ+ equality in America, due to premiere in January 2020. To pay for his coffee and his dog’s pampered lifestyle, he writes full time for communications and government affairs in the realm of healthcare.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE