Blue jay lessons and spells

I slouch low in the Adirondacks Dad built for the porch, hidden behind the juniper bushes, smoking tobacco and herbs. Mara’s thinning ponytail sweeps her shoulders, dull in the morning sun. She speed-walks up and down the block, where her parents can see out their window. Blocks gossip, but, rounding the cul-de-sac, I could’ve guessed she moved home for treatment. I wonder which program—the one that did nothing for me? The one to avoid like the plague? Her frenetic gait echoes in my legs, a memory of ache. My clothes are a bit roomy these days, but more than that, I’m sallow. Wilted as the dry, bleached remains of my curls. Does Mara know I moved home, too, another neighbor kid flunking adulthood? If I walked past, could she read synoptic history in my hair?

My thoughts are homemade fireworks, bright and erratic, a panic of loud. Anyone who looks at me knows what I ate this morning. I don’t want to be seen.

—

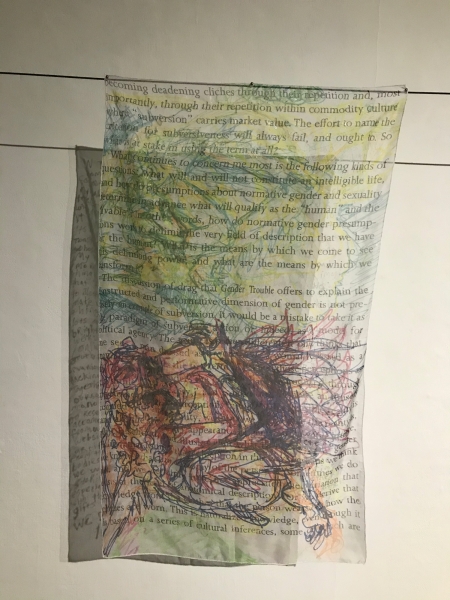

Kneeling at the altar of my bedroom floor, nights pass in a fever of symbols. First, graphite and india ink, then watercolors, pastels. I string my childhood bunkbed with clearance fairy lights. Half of them don’t light up anymore and I’m too tall to sit upright in my bed.

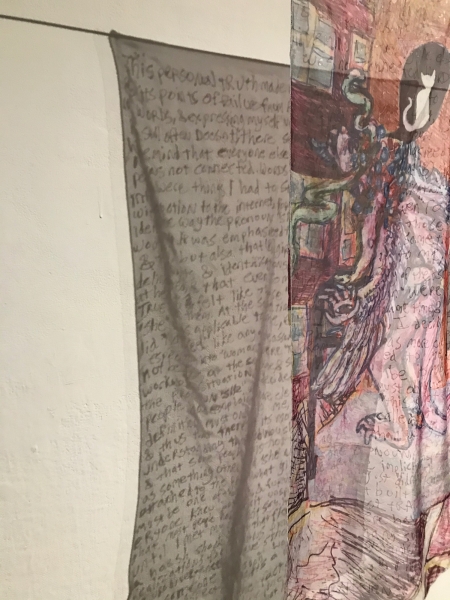

Eyes prick my skin with their static. It feels the same as it did as a child, when people watched through my mirror. I locked myself in the bathroom, alone, pressing the tip of my finger to glass. A kid at school said if your reflection touches your finger, one side’s a window and someone could watch. Half a centimeter remained between me and myself. No one watched from within the walls, so they must’ve used cameras or magic.

I made a silly face in the mirror and though: Have fun watching me brush my teeth.

I picked my nose at them for good measure. I’m not afraid of you.

Now, I let the moon in, blinds open well after dark. I draw a self-portrait with antlers wrapped in trumpet vines. When Mom comes in to say goodnight, she winds around art supplies on the floor to close the blinds with a twist.

“Someone could see right in,” she says.

I don’t say: They can go fuck themselves. I want to make art with the moon. I crack them open, just a little, when she leaves.

—

My days soar on winds separate from weather. I’m punctuated. Sudden drops impale, spikes of terror and dread. I vibrate like a tuning fork. With my parents, I try to measure my words, rapids through a sieve. I try not to think the word hospital, in case someone hears, in case thoughts bring things to be.

My ears ring constantly. I track the sound through the house. The high pitches get louder near plugged-in electronics, even if they’re turned off, but my bedroom is loudest of all. At first, I think I’m just hearing berms of my bodily energy built up over decades. Then, I notice the singing. It oscillates on my skin, teeny-tiny multitudes, like carbonated sound.

I have a set of three wooden bowls placed here and there around my room, holding sundry pretty things; trinkets I’ve picked up from the ground, old friendship bracelets, small fossils. The bowl on the bookshelf holds two handfuls of beads. Chips of quartz varieties: smoky, rose, aventurine. They sing—every stone, singing. It’s beautiful. Loud. Sonic energy lifts the hair on my arms as I approach. I pour some into my hands. A few drop to the carpet beside my bare feet.

They sizzle. They actually sizzle. They bubble in my hand. Eyes wide, I laugh, remembering Pop Rocks that turned your tongue green.

It’s some dark hour. Cats and parents sleep. I secret the beads into a thin tulle bag and hide them in my sister’s old bedroom, under forgotten sweatshirts in the dresser that matches my own. When I crawl into bed, the ringing isn’t so loud as it was. Even so, my body still vibrates.

—

I’m exhausted, wide-awake in bed, fairy lights on and eyes closed. In my mind, I’m in the garage, in the Honda, the garage door closing behind me. I park and turn off the car, get out, and two men accost me. They snuck inside when I wasn’t looking. One wields a hunting rifle. They came for my mom and for me.

How might I protect us?

In the world we agree on, my mother serves a church as a solo pastor. Her congregation works with Reconciling in Christ, a process training them to welcome, invite, and be safer for LGBT people. The men in my mind want to punish her for it. For birthing me, too.

The scene plays out in fractal, over and over with minor evolutions. I work through each variation: What if I scream? Fight? Jump back in the car and punch it through the closed garage door? With each run, I learn, refining my choices until it feels right, like I’ve learned something new. Like we’re safe. But no matter how I changes I make, I can’t change the premise. I’m always closing the garage behind my parked car before I get out.

In the world we agree on, I park in the drive way, not the garage. It doesn’t make sense.

—

My dad built a bird feeder shaped like a trough for the deck. Squirrels love it. It’s fastened to the white banister, framed by the family room’s bay window. Birds fly in to feast from our cottonwood trees and the woods beyond the swamp. Once, I saw chickadees, gold finches, cardinals, robins all eating together at once. Then, two blue jays dive-bombed the banister, expansive, territorial. They chased the smaller birds away, but ate nothing from the trough.

A squirrel scampers across the banister with seed-heavy cheeks beyond my mom’s heaving shoulders. She sits in the light of the window in sweatpants, Kleenex beside her. She neglects the crossword in her lap; pen doodles fill up the margins. For three days, Mom stays home from work, sits on the couch, watching reruns, and cries.

—

I can’t remember his car. Dad emailed pictures to block and cul-de-sac so the neighbors can keep an eye out. I’m no longer allowed to park in the driveway; from now on, Mom and I both shut the garage door behind us before we get out of the car and Dad parks where I parked outside.

I can’t remember his name, but Mom says he becomes someone else when he’s drunk. She asked if she could share that I was queer with her congregations if it became professionally relevant. I gave her permission and she preached about me, an example among other stories. Most of the poisonous rage he spat into her voicemail was for powerful women leading the church. But he mentioned me—he remembered.

It’s dark out when I pull into the garage. I sit in the driver’s seat, car off, doors locked against the creaking silence of an engine cooling down. Bare bulbs buzz above me. Threat echoes in the emptiness. If this is too much like my imaginings, it’s too unlike them, too. In my head, I could maneuver. I could choose, reap consequence, learn. Here, alone beneath the rafters full of old sleds and cross-country skis, there’s nothing to outsmart. Only words I never heard, deleted after statements were made and evidence collected.

Tonight, somewhere else, a man drinks until transforms into another man, or he doesn’t. I find myself violently safe.

A fear-shaped space moved home with me, a door held ajar by my thoughts. Maybe that’s how his words slipped into our lives. Or maybe my third eye needs glasses.

—

My parents installed the hot tub years ago, but I use it now more than ever. I turn on the basement fireplace before I go, so it’s warm when I return. The hot tub steams up through the screens that contain it, billows caught in the floodlights that illuminate the foreground cottonwoods, middling swamp grass, the dark backdrop of woods. Anyone looking in would see nothing. Not the robe I hang on a hook by the door. Not the nothing I wear, slipping into the water.

I imagine the man rounding the east or west corner, stomping downhill along the house to break into the basement. It doesn’t feel real. There, though, at the edge where the woods meets the swamp, that place is real. He’d stand there in boots and jeans, hunting rifle in hand, squinting to see past the lights.

I know he’s not there. I don’t know that at all. I flip the bird at his negative space.

I’m not scared of you.

A red light blinks in the darkness. I don’t know what from. My limbs boil limp as noodles. Back inside, I stretch by fire. After a while, I turn on some music and turn off all but firelight. I dance with invisible ribbons and orbs, pulsing colors, pink, indigo, teal. Tangible, I gather and move them with gestures and breath. My body unwinds. They touch me, pull at my sternum. A sun spins. Luminous mountains climb and rise to the beat, small as stalagmites.

Are my eyes open? Does he watch through the window?

I climb onto the love seat and lean over its back to press my finger against window glass. It’s double-paned. My reflection touches me and it doesn’t.

—

Mom goes back to work. Her community rallies after the threats, stronger than ever before. Dad’s at work, too; so is most of the block, but I can still feel someone watching. Backyard, the deck, slunk low behind juniper, someone touches my skin with their gaze. I check for Mara walking laps before I trot down the driveway. Maybe I speed-walk a little, too, just to pass faster, less chance to be seen.

Down where this street meets the next, I turn onto the path to the park. There’s a perpetual groove in its pavement where the swamp reclaims the land with flood every spring. I cross it and stop at the edge of the woods. The breath of the trees presses against me, an envelope. I step through still, gum air.

My shoes rest, obscured by the base of a tree. I leave the pavement for a cold dirt path into the small wood. It’s thinner, now. Dad’s been on a crusade against an invasion of buckthorn. Their bodies line the edge of the path. I light an herby cigarette. Mullein fluffs up the lung clouds like vapor or steam. Blue lotus brightens the colors. The lavender scorches, but I love how it tastes.

I walk barefoot on the thin fallen trunks, toes gripping lichened bark. My balance is shit, but the soles of my feet feel alive on tree, loam, and stone. The path leads me to the white rock doming up front the ground. I hop onto its turtle shell, smudge it with toe prints. The, down and around, past a buckthorn cemetery, down to the swamp across from my backyard.

I stand where I imagined him standing. The man whose name I don’t know, whose car I forgot. I look for boot prints in the mud. If the swamp knows this man, it won’t tell me.

—

There’s a shooting at Pulse Nightclub. I wake up to the news. Mom and Dad are already gone, off to the first Pride fest of her church’s small city, where she and other clergy are to lead a collaborative worship. The man lives in this city. I can’t leave the house.

It’s easy to picture her out in the sun, green grass and a hill, some oak trees for shade, and Mom, in alb and stole. It’s easy to picture her smile, the glow of her freckled face whenever she’s in her element, the professional version of the joy she feels when all her babies are home. It’s easy to picture a burst of bullet, blood, my dad weeping, trying to save her. Maybe he’ll get shot, too. I hover, above and behind myself. I want to turn off June.

Five years ago, my mom asked if she could preach about me. I’d spent the year watching posters melt off cement classroom walls, overmedicated and lost. Mom made it clear that I could say “no.” I said “yes.” Even then, still an angst-riddled teen, I knew this wasn’t about me. It was about the hundreds of people who listened to her speak from the pulpit, who struggled, or loved someone who did. People cried during her sermon. They poured into her office, seeking resources and solace. So many parents, no longer alone in their fear for their child.

Church changed that day. People looked at me different. Despite the broad, discrete strokes Mom painted with, strangers knew an intimacy of me, unreciprocated. They knew why I fled service to hide in Mom’s office, but I didn’t know them.

Once, my mom told me, “I don’t know anyone else who’s helped so many people they’ve never met.”

These words are not a pat on the back; they’re affirmation of choice. Sitting on the window seat overlooking the swamp and the woods, where the blue jays nest, I know I’d make the same choices again. Mom would, too. Madness or queerness, it doesn’t matter. We’d both do it over again.

And I’m afraid.

I’m so afraid.

I’ve never known such fear.

I get up from the window seat and pace the route I used to walk in middle school, gabbing with friends on the phone. The cats snooze away on the back of a couch and I give each a grief-wet kiss. Mom asked us to play Jupiter: Bringer of Jollity from The Planets at her funeral. I turn it on. I can’t pace anymore. I can’t hide or walk away from the clawing in my ribs. I know my mother will die. She won’t be murdered standing tall, but crouched to greet someone’s child, eyes crinkled up by her smile. Dad would take a bullet for her if he could. A well would fill overflowing with all this pride, this grief, this love. In a heap on the hardwood floor, I’m crying and crying and crying.

Mom comes home sun-kissed and sunny in lime green t-shirt and shorts.

Face dry, I ask her, “How did it go?”

“Perfect,” she says, breathless, as though she’d jogged the whole way home. “Fantastic turnout. We couldn’t have asked for a more beautiful day.”

She hugs me. She smells like grass. The garage door stays open all day, breeze dusting across cement floor.

—

I walk barefoot through the woods again. The sun shimmers down between petals of green and everything smells like its growing. I’m joyful, thoughts like a babbling brook, like staring at the sun. Perched on the bright breach of pale boulder in the middle of the path, something magnetic tugs at my breastbone. Giddy, I giggle out loud to myself, close my eyes, and follow the pulling. Flickering small-lights and long strands of color lead me east, away from the rock. Pale blues overlay on the path beyond my sun-bloody lids. Feet quest, stumble, and prick. I turn. There’s a fork in the path, both running south to the swamp.

I peek, slit-eyed. My vision says left. The tugging says right. I try left, then double back when my heart starts pounding, heavy. Still peeking, I walk down the right fork to find three feathers, blue and striped. I find another. Then, the whole bird, a blue jay, dead in the brush, as though he’d fallen right out of the sky. There’s cacophony inside me, frightened, exuberant. I dither a moment, then I race home to grab a plastic bag.

Mom asks from the kitchen, “What are you up to?”

“I found a dead bird. I’m want to bring it home to bury in the garden.”

She eyes me, uncertain. I feel flush on my cheeks, but I grin, grab the bag, and run off. I try not to think the word hospital. Back in the woods, I gather every bit of the bird I can find. It seems almost sacrilege to carry his body in plastic, but it won’t be for long.

I carry him home, sun high and hot. Neighbors work in their yards. We wave hello. I pop into the open garage to grab gloves and a trowel. My feet squelch through a soggy patch of lawn on my way down the hill to the garden by the swamp. Dad gathers fallen branches and rakes while Mom lays out fresh mulch. They’re sweating and scratched, breathing hard from their labors. They’re happy.

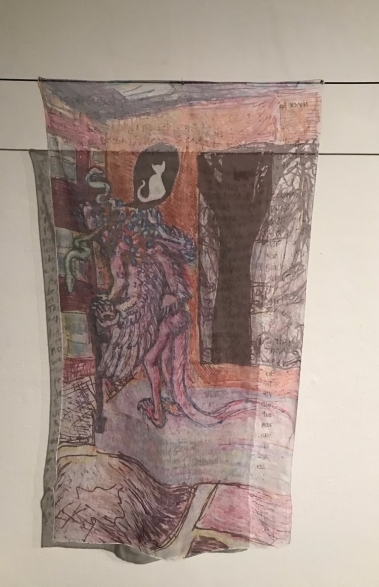

Both shoot me questioning looks, but they leave me to my toils. There, where anyone could see, I dig a hole in the dirt. I keep two feathers, the rest of the bird laid to rest. Once covered, I choose five river rocks and press them in a design above his body. Small branches are broken. I shut my eyes and incant something silent and pagan, homemade.

It’s dark, somehow. When did it get dark? I walk the yard’s periphery and find myself alone. Lights on, I can see through the windows, the outside looking in. Dad’s at the kitchen sink, head bent over busy hands. Mom sits at her favorite spot on the couch with her crossword, some procedural on the TV.

At the northernmost edge of the yard, where grass meets the swamp, I press a stick into soft turf, one feather stuck upright, like a flag. East, then south, halfway up the hill, a stick pressed into the ground. South to the curb, then west, I find the southernmost point and press in a stick. West, then north, halfway down the hill, the final stick, stuck in the ground. North again, I walk until the circle’s complete, to seal in the magic.

I hold the final blue jay feather in my hand. Overhead, first, I feel it fly, then I see it with closed eyes. It’s beautiful, loud, a little uncouth, fiercely protecting its home.

E B Joy lives in a little cottage near a river and some lakes. They graduated from Hamline University with a BFA in Creative Writing in 2020, where they contributed to Runestone Literary Journal Vol. 6 as a student editor in 2019 and were awarded the Ridgeway Fellowship for their Summer Collaborative Undergraduate Research, Summer of 2020. Forever Falling Sideways by the Icarus Project published their work in 2013 under a different name. Joy is an active member of the Hearing Voices Network’s local chapter and a Certified Personal Medicine Coach.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE