The Perfect Chord

By Laurence Suhner, translated from the French by Sheryl Curtis

This evening, I’ll finally do it.

My fingers will assume the ideal position, they will pinch the strings with the adequate amount of pressure, neither too strong nor too weak, so that the vibration will attain the desired frequency; they will find the correct tempo; will extend their combined efforts toward perfect harmony. The sound will grow, amplified by the large sound box. It will fill the space with the necessary volume, a mixture of delicateness and strength, of gentleness and intensity. I’ve been aspiring to this for months. It’s no more than a matter of tiny adjustments. I feel it.

I can already imagine the power washing over me as it once did, over there, very far, very high in the sky, during that night spent in the immense primeval forest of Edena, a small telluric planet in the Tau Ceti system, the second to be discovered by our astronomers. An inhabitable exoplanet, as they used to say at that time, three centuries earlier. Now, we’ve gone back to the good old reflexes and we simply call it a colony. Tau Ceti, a system twelve light years away and yet, the heritage of humanity.

Night fell over the village several hours ago.

I’m sitting in the circle, almost in the middle of the clearing, where smoke rises from the bonfire and the torches. I see the moon making its way through the gap in the foliage overhead. Around me, a handful of the members of my expedition, weary faces, drawn features, yawning as they wait for the opportunity to go to their tents and abandon themselves to rest. As for the others – the natives, let’s say – they observe us without seeming to do so, glaring, if that expression applies to their insectoid faces, their multiple, impenetrable eyes. Like bottomless black lakes.

Edena was not supposed to shelter life. Much less, intelligent life. If such primitive creatures can be considered intelligent beings,which, despite everything, I’ve forced myself to do. Since I arrived, three earth years ago, I’ve made every effort to keep the necessary distance, to avoid judging, to avoid making the same mistakes as my predecessors. I try to understand their habits, their customs, even though they’re nothing like anything I may have encountered on Earth. I’m a true ethnologist. Except that there’s nothing human about my subject.

This evening, it’s my party, literally and figuratively. The natives have organized a ceremony for me. At least, that’s how I understood it. But it’s also possible there’s no connection. Many things continue to slip past me, despite my efforts. Perhaps this festivity coincides with one of their celebrations honoring the moon, the stars, the seasonal rains, the laying period. What do I know?

The heat is stifling. Despite being specially designed, my clothing sticks to my skin, to such a point that I wonder if I’ll be able to extricate myself from it when I go back to my tent at the end of this exhausting day. I’ll have to. I leave tomorrow.

After three years on Edena, my feelings are mitigated. Obviously, I‘m happy to be going home… The suffocating heat, the sickness, the insects as large as crows that dive at you, the unbridled, voracious fauna which has eyes for nothing but your meager rations, or for you… Not to mention the incomprehensible culture, the barbaric, often bloody practices… The S’fars, as they call themselves, are pure animists, hunter-gatherers barely out of the paleolithic stage. We have nothing in common with them.

At the same time, I feel a vague sense of regret. I wasn’t able to do anything. Apart from saving their lives. And as for any guarantee that my efforts will be continued by my successor… The first plan was to eradicate them. No one back on Earth would have known. When we arrived on Edena, we carefully omitted making any mention of the discovery of intelligent life. At the start of my mandate, five expeditions later, I temporized, I knocked myself out looking for traces of art, painting, writing, funeral rites… The jewelry they make with any old thing and display around their long, slender necks, like that of a praying mantis, their grasshopper-like legs, devoid of flesh, the grotesque trinkets they shake, the rawhide drums they beat with an obvious lack of rhythm, all that is art! I shouted at my colleagues. They shrugged, snickered on their large tractors, their excavators, turning over the rich forest soil, looking for oil, gas, uranium, diamonds. We’re here to grow rich, they told me, to dig the soil, to take control of the resources, to adapt the environment for the upcoming arrival of millions and then billions of people from Earth, weary of breathing in the poor, dry air of our dying world. Edena will be our world soon!

Without me, without my patience, my persistence, the S’fars, decimated by human colonists, would be decomposing in the thick strata of vegetation in their planetary forest. They would be one with their planet. Perhaps it would be as if they had never seen the day under the yellow light of Tau Ceti. Perhaps that would be better. For them, for us. Who knows?

I focus my attention back on the center of the circle. The racket is deafening. The natives – a good hundred in number – are rubbing their elytra in a rapid, jerky movement. The rustling overlaps, multiplies, saturating the space. It’s unbearable. In the middle of the clearing, one individual, even rangier than the others of his kind, is waving his upper limbs in a hypnotic choreography. Four arms, ending with two fingers that look like claws. The gestures are slow and precise, no doubt pregnant with meaning. Looking at him, he could be taken for an oriental divinity. I tap a few notes on my console. The creature is dancing. I’d bet my life on it. I can’t help but find it beautiful in a certain way, a sense of grace filled with nobility, which touches me despite the racket, the heat, the humidity and the exoticism of the situation.

Behind me, Stephen, my assistant, sniggers.

“They’re going to marry you, that’s for sure!”

I turn around. He’s as red as a beet, as red as the S’fars are a dark, deep green. He continues, jabbering in a way that pleases my colleagues, spluttering to his heart’s desire. Then he’s seized by a coughing fit that drowns in the mouthpiece of his respirator. Fortunately, that puts an end to his childish nonsense. Some of my colleagues here are laughing, some crying, some coughing.

I resume my contemplation. I have nothing in common with those guys. I came to this world to understand. I learned what I could. I saw. I felt. I will never forget. The experience is engraved on my mind, my heart, my entrails, like a brand. These people may be barbaric, but we can’t just deny the fact that they exist, wipe them away with the back of a hand.

One day, when I’ve recovered from these three years spent battling in a hostile environment, I’ll come back here. Despite a gravity forty percent weaker than on Earth, Edena is hell. It will have to be worked to the core, gentled, prepared for colonization. That’s the job of the next expedition. The large carriers are on their way. Everything has been planned. In 50 years, this planet, terraformed by humans, will be our second cradle, a new chance for humanity. I’m proud to have been one of the movement’s pioneers. But, somewhere deep down, I already feel nostalgic for this wild nature.

The laughter – again with that allusion to my marriage! – grows behind my back. It struggles to dissipate in the dusty air mingled with the odor of the local cuisine. Since this morning, something has been stewing in a large furnace. There’s not a breath of wind to freshen the clearing, which is imprisoned in this virgin forest filled with the perfume of the start of the world. “They’re going to cook you!” the men couldn’t keep from joking.

I’m weary of their never-ending nattering. I’m preparing to gratify my team-mates with a searing remark, but no sound comes out of my mouth. I should do like them, shout over the din. Talking makes my head hurt, so imagine raising my voice… I cough, make an effort to put on a fake smile. I see Stephen wiping a tear away on a corner of his shirt. People here laugh at anything. At anything. Everything is a pretext. It’s the wear and tear, the fatigue of this world which weighs too heavily on our bodies. Too much boredom, too much heat, too much strangeness, too many natives with their obscure customs. Those I recorded and catalogued so doggedly in my console. Over 1000 pages. When I get home, I’ll write a long, well-documented article. I’ve gathered enough information for the Planetary Commission to establish a reservation. Thanks to me, the S’fars will have their own land, a bit of this vast forest with its swamps, its tree-like ferns, its thousand-year-old trees that stretch 300 meters up. I’ll make sure they’re comfortable, that they can live decently, that their ancestral traditions are respected. I sincerely hope that will be enough to protect them from the brutality of men. The reservation is an acceptable solution, compared to genocide, the preferred option. I’m returning to my loved ones – my wife, Celia, and my children – with a clean conscience.

A new commotion is sweeping through the S’fars. The one I called the dancer is discreetly withdrawing, melting into the mass of his kind. He has no further role to play in the ceremony. Other natives, all limbs and exoskeletons, have just placed something in the middle of the clearing. It’s huge. At first glance, it looks like a piece of wood with several elements and fine stems, stretched along a handle, that sparkle in the light of the fires. The clamor grows in intensity. Then, suddenly, silence falls. No rustling of elytra, no pounding, no growling, no cries. Even the forest, usually overflowing with the stirring of creatures, falls silent. The S’fars stare at the object standing in the middle of the clearing with their black eyes. One of them slowly walks ahead with its four slender legs. It’s a new one; I don’t recognize the markings on his shell. He bends forward, as if bowing, and then places one of the appendages that serve as hands on the object. The gesture is respectful, somewhat sensual. When his claw touches the stems of threads, strident sounds are produced. A long task starts then: the native catches the threads one by one and modulates the tone using what looks likes wooden pegs screwed into the handle.

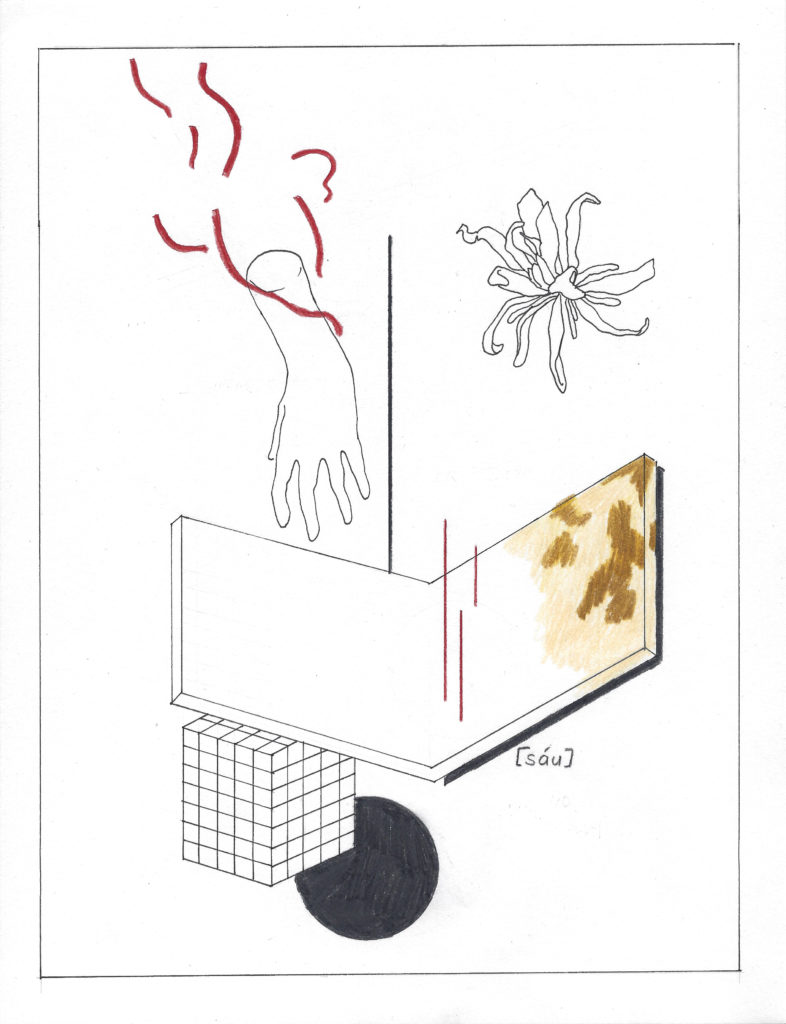

A sound box. Neck. Strings.

What I’m looking at is a musical instrument.

Using a camera, I obtain a closer view. The object looks old and dusty, a common piece of poorly worked wood. Perhaps they dug it up from some ancestor’s tomb? In any case, that’s the impression it gives. In the three years of my mission, I’ve never seen anything like it. The S’fars are better known for the diversity of their percussion instruments. No doubt they keep the newcomer for major events, such as my departure. Despite my efforts, I’m unable to count the number of strings. Fifty perhaps? Maybe more? Long and shiny, a gap of two or three centimetres between each of them, rising from the saddle, over the bridge and spreading out on both sides of the neck – 1.5 meters long by the looks of it – and finally winding around pegs. Metal? Fishing line, as in the case of certain, old-fashioned lutes back on Earth? Or organic, animal or vegetable fibers? Under the player’s claws, the strings tighten one by one. The native is looking for the adequate frequency, in the same way as people would tune a guitar or a violin. The sound is unpleasant, sharp and resounding.

“We’ll leave you with the bride, eh?” someone says behind my back.

Out of patience, my colleagues have started to leave the clearing.

I force myself to resist for a moment longer, then decide, in turn, to follow them, overwhelmed with fatigue. I don’t make it a meter. All of the natives stare at me. They want me to stay, for me to attend the ceremony until the end. “It’s for you,” the one we’ve taken to calling the chief of the village, nattered this morning in his colorful language. “It’s an honor. You have to stay until the end.”

For me. Just for me. What does that mean? Is it to thank me for all my efforts? Do they understand that I’ve fought to save them?

I sit back down and their attention immediately shifts from me back to the musician, who devotes himself to his art. Bit by bit, the sound transforms. I notice a harmonic progression. I can make out notes. I practiced an instrument when I was young, as a means for training my brain. I recognize full tones, natural, but also semitones, sharps and flats. I also detect smaller intervals. Quarter tones? The tuning is very subtle. And takes a very long time. How can this native perform such delicate work with the coarse claws at the ends of each of his upper limbs?

The tension in the clearing makes me feel uncomfortable, almost ill. Something is happening. But I couldn’t say what. Something that floats above the notes and my understanding. Something primal, fundamental for the S’far culture, something that escapes me. Why didn’t I have an opportunity to attend such a ceremony during the three years of my mandate? Why did this have to happen the night before my departure? I had no idea the S’fars were such accomplished musicians. How could I have missed that? Suddenly, I’m angry with myself. I did my job as an ethnologist badly.

The moon, the planet’s sole moon, is high in the sky. And full.

Overcome by the heat, I must have fainted for a moment. Silence bathes the clearing. I notice that all eyes are fixed on me.

What are they waiting for? For me to wake up, of course! They want me to give them my full attention. As soon as they realize I’m fully conscious, the concert begins… How else could it be described? I’m immediately caught up in it. I’ve never heard such knowledgeable music, so subtle that it transports me, literally, into another world. Yet, my ear recognizes no melodic composition. It’s something else. As if my perceptions have been modified, expanded, to enable me to access different ones, those of the S’fars. As if I’m discovering, for the first time, senses that remained unknown before this. I see things in the combinations of the notes. I literally see them. As if I could reach out and catch them, one yard in front of me. Colors that burst, shapes that take form in the air, fireworks of light that cross through me. I see S’fars walking ahead in the millions, gigantic cities that rise above the forest, like ant hills, spacecraft criss-crossing the cosmos to the very edges of the universe, planets, stars, galaxies… I’m watching a high-speed presentation of the history of a grandiose civilization as it once was. Unless what I’m seeing is their visions of the future… Or a simple dream. After all, the S’fars are merely a primitive people, without technology. They don’t have flight, let alone space navigation. But regardless of the nature, the illusion is captivating. As I listen, I feel jubilation grow. A physical, almost sexual joy, washes over me. I regret that my colleagues left early. Well, not really. Would they have understood? I’m flattered by the honor the S’fars have reserved for me. They chose me. That’s why they insisted that I stay until the end. I alone could understand.

How long did my modified state of awareness last? I couldn’t say. In the morning, I find myself lying on the grass, exhausted but ecstatic, my clothing damp with dew and perspiration, bathed in a sensual pleasure that balks at leaving my mind and body.

A young native is standing in front of me, recognizable by his dull shell devoid of marks and his slender build, proof that he has never laid eggs. He holds the instrument at his side. He speaks to me in his language.

“It’s for you!” my AI translator immediately transcribes.

A gift?

Am I entitled to accept it?

“I’m very honored. Thank you,” I reply

The young native bows and hands the object to me.

“And the musician? Where’s he?”

“He’s… dead, as you say in your language.”

I stand up suddenly.

“Dead? I don’t understand. Why? How?”

“He made the sacrifice. That’s tradition when one plays the H’la, the Great Harp/Lute of Transformations. Now, leave. Go home. Take the H’la with you. It’s a gift from my people. If you don’t take it, the sacrifice will have been pointless.”

Already, the native is walking away, taking small steps. It’s impossible to determine if he’s proud at accomplishing his mission or sad about the loss of his fellow.

“It’s all for you,’ he said. “That’s what counts.”

My hand settles on the body of the instrument. The sound box is made of a large fruit, much like a very large squash, cut into halves. I brush my fingertips against it and it seems to me that a slight vibration runs through me, as if the music of the past night were waiting to come back to life through the fibers of my being. With ease, I lift it and the strings quiver in the fresh, dawn air, gratifying me with a few random notes. It looked heavy to me the previous evening when the S’fars placed it in the middle of the clearing. But gravity is only 0.6 g on Edena. My human physical strength is much greater than that of the natives.

I don’t know what to do. I’m tempted to leave the H’la, the great harp-lute as the young S’far called it, right there. Something tells me that this splendor does not belong to me, that it should remain with its people. Then, I give in. I pick it up and take it with me. It seems so light in my hand.

Other rustles respond to the murmur of the forest as it awakens around me. Bit by bit, I notice groups of S’fars watching me through the foliage. Their eyes follow me until I reach my quarters. My ship takes off in a few hours. All my belongings have already been packed in trunks ready to be loaded.

In the brilliance of the morning sun, standing against the wall of my high-tech tent, the harp-lute has lost its magnificence: it has once again become a simple dented shell cut out of a large, hollowed out piece of fruit, with myriads of strings of varying sizes and diameters. I’m astonished by the state of fascination which it plunged me into yesterday. Was there some hallucinogenic substance in the air, spread by the smoke of the fire? It doesn’t matter. Its raw, primitive look, its dark wood will be all the more appealing in my living room with its white walls and platinum gray furniture with rounded corners.

“So, what about the wedding?” someone says behind my back.

That schoolboy joke will follow me until I give in to cryogenic sleep on the ship. I walk past Stephen without stopping. I know he’d like to be in my shoes… leaving.

“Why are you taking that horrible thing back?” he insists, sniffling.

“It’s a souvenir. Just a souvenir.”

“Well, I don’t want any souvenirs from this place! If I were you, I’d chuck that old thing in the garbage. We have to make a clean sweep of this damned forest and those cretins!”

I take my leave without another word. I’m going to talk to the Commission, that’s for sure. I won’t leave the S’fars in the hands of guys like Stephen. They’ll have their reservation.

The cabin I’m assigned in the ship is comfortable, but small. I would have liked to keep the instrument there, close at hand, to make sure no one touches it – it’s funny how I’ve already grown attached to it – but it had to go through a complete decontamination process and was placed in a hold, appropriately packaged. I’ll have to wait for the end of my trip. Ten months. That may seem long, but it’s not really. I’ll sleep until we cross through the gateway, the Einstein-Rosen bridge that will take us back to the solar system. Thanks to the theories of Ermann Lô Yuko at the beginning of the 22nd century, interstellar travel has become a reality. Without it, we’d still be subject to the limitations inherent in special relativity. To get to Edena, I’d have had to spend centuries in a space craft with no hope of seeing my loved ones again.

I prepare for stasis. The ship’s AI will watch over me, as well as a hundred or so colonists who are returning home with me. I’ll wake up in orbit around Mars, fresh as a rose. From there, I’ll take a conventional carrier that provides a regular shuttle service between Mars and Earth. A simple formality. I’m eager to get home.

Here I am. The harp-lute stands in a glass case in the middle of our living room.

Of course, my wife, Celia, who I find looks more careworn and tired than I remembered, doesn’t like it. My children, Maxime and Jessica, 12 and 15, danced around it, delighted and excited. As for the little one, Leonore, who was only two when I set out for Edena, she ran and hid in her bedroom as soon as I took the instrument out of its crate. Five-year-olds aren’t impressed by anything. All she knows of the world is our sanitized civilization, without glitches, defects, dirt or the slightest trace of dust. No plants or flowers brighten our apartment and the trees that line our street are artificial, obviously. We have to save our air and our water. We don’t enjoy the luxury of sharing them with other living creatures, let alone with green plants.

I was overjoyed to be back with my wife and children. Yet, why am I so indifferent to their presence? I don’t understand the source of this feeling of apathy. My doctor told me it was shock, the trauma resulting from my confrontation with the other. Basically, the consecutive side effects of a long and difficult process of acclimation. Apparently, I experienced acculturation. Rehabilitation will take time. Perfectly normal. I let him talk. He prescribed rest. So be it. I make the most of my days at home to write my report on the S’fars for the Planetary Commission.

“No bulldozer or excavator for two thousand acres,” I stated in black and white. I have to be firm.

I’m satisfied. I’ve written a powerful article and submitted it to the Commission. But, meanwhile, I got sick. As I lie in bed, fighting an inexplicable and sudden exhaustion, my youngest daughter, Leonore, brings me a mug of hot chocolate.

“Daddy, you should take it back there!”

“What, sweetheart?”

“That wooden thing with the strings!”

No doubt in an effort to be explicit, she covers her ears with her small hands.

“At night, it plays all by itself in the glass case. I don’t want to hear it any more. Daddy. It’s… bad!”

I chuckle gently. My daughter has a vivid imagination. If I don’t keep an eye on things, she could turn out badly, become an artist. A frightening word. That would bring shame on my family, although I’ve softened my tone since that night in the clearing on Edena. Music, as long as it remains practice, has a purpose in the sense that it serves to create new cerebral connections. In that respect, it is beneficial for the development of children. But for them to become musicians or, worse yet, painters or writers… fortunately, there are treatments for that. To nip the evil in the bud, so to speak. I hope we don’t get to that point. Leonore is little. It’s too early to make a big deal about things.

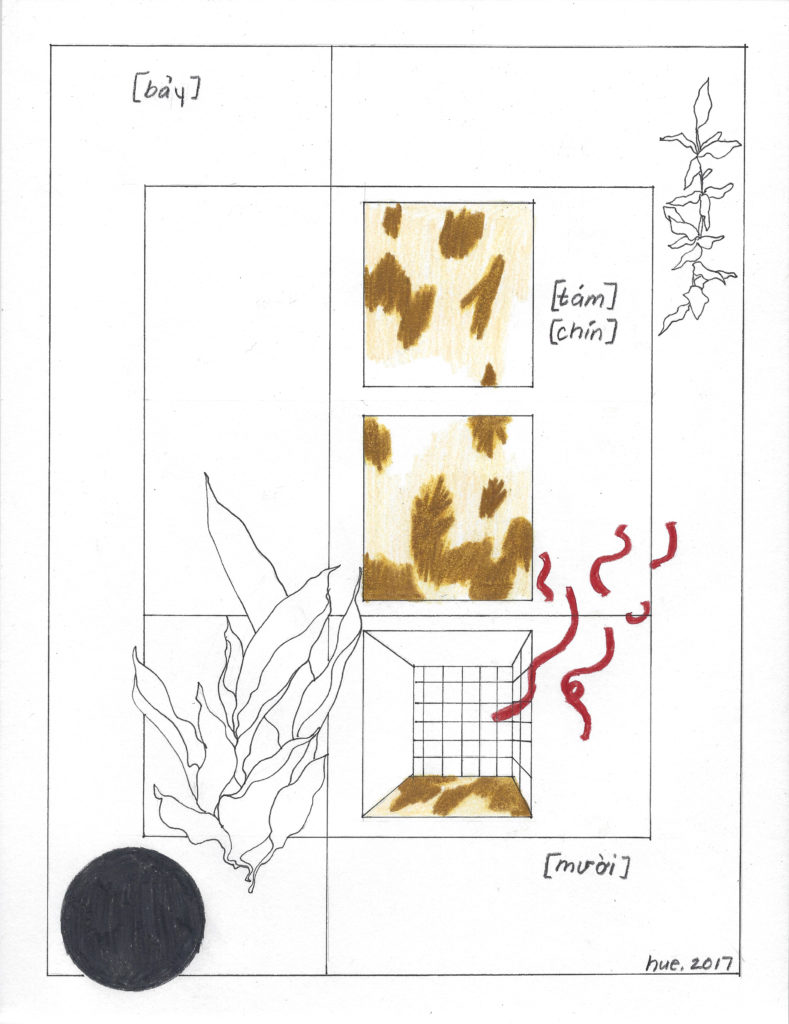

A month has passed. Fully recovered, I’m spending more and more time in the living room. One evening, glass in hand, I decide to take the large harp-lute, the H’la, out of the glass case. I place it gently on the couch, next to me. Of course, in this incongruous décor, its aura of mystery and exoticism has melted like snow in the sun. But its strings sparkle in the cold light of the apartment. I have no claws at the ends of my arms. Plus, I only have two arms, but perhaps… cautiously, I slide my fingers over the strings. The sound I produce is very distant from what I heard that night in the clearing. My hand moves up to the wooden pegs. They’re used to tune it! I have to find a melodic landmark. I dig through my childhood memories, trying to recall the drills, the scales I practiced up and down on my violin. I had a very good ear according to my instructor. This might be a “C”. Or perhaps a “C#”. I search. I grope my way around. And there, isn’t that a “B”? I identify the intervals, marvel at the subtlety of the stringing. Octave follows octave along the length of the neck in quarter tones.

I get down to work. First, I take a chance, using only my ear, then I find help in my AI console. Frequencies and harmonic progressions are the same everywhere, on both Earth and Edena.

I decided to extend my convalescence and stay at home. I still haven’t had any news from the Planetary Commission about my article on the need for creating a reservation for the S’fars. My wife left early this morning with the children. I caught the frightened glance of my youngest, Leonore. She heard me last night. Maybe she even saw me when I locked the harp-lute up in the glass case. With a certain amount of jubilation, I take it back out, and set back about tuning it where I left off the previous night. It has so many strings. Given the change in pressure, temperature and humidity – it’s much dryer here than on Edena – the H’la seems to enjoy growing sharper as I progress. I have to constantly go back, turn the pegs, to the left, to the right, to fight with wood that creaks, with strings that wail and vibrate at the risk of breaking. What frights all day long! The H’la fights me fiercely. For now, the notes I torture from it have none of the exquisite musicality of that night in the clearing. It’s painstaking work, but I persevere, step by step. I want to hear its perfect sound again, the complex harmonies that caused my visions, the total joy of body and soul that no earthly happiness will ever be able to match.

I’m a bit stubborn. All it takes is patience, constantly getting back to work. One day, I’ll succeed, I’ll reproduce what I experienced that night under Edena’s full moon.

Sick again.

I vomit. My hair falls out in clumps. This morning, I even lost a tooth. No doubt a result of the deficiencies harvested during my time on Edena. I have a good reason to stay at home. This way, I can work on my instrument without stopping. What’s a little physical discomfort compared to the endless immensity of the pleasure that modulating sounds, fine-tuning frequencies brings me? I dedicate my days and nights to it. I no longer sleep. In any case, I’m no longer tired. What’s the point of wasting time?

Around me, I see concern. In the building, in the street, on the news I watch from time to time. This morning, I even felt it for the first time: an earthquake. For ten days, the news has talked about nothing else. Our Earth is stricken with incomprehensible tremors.

I shrug it off. I think of Edena, its large rivers, its luxurious swamps, its dangerous animals and its conscious creatures, its exuberant youth. A musician gave his life to play the large harp/lute for me, the instrument that is now resonating under my human fingers. Another string, then another. I adjust, I finetune, I constantly go back to orchestrate the harmonies, to cavort with the waves transmitted by the vibration of the strings. The sound grows refined. I already find it much less discordant. I’ll get somewhere, that’s for sure. I thank nature for giving me such a good ear.

I would have liked so much for my wife and children to hear this. But they left a month ago. Celia returned to her parents’ place to wait for my whim – her word – to pass. Apparently, I was frightening the children.

She doesn’t understand anything. She never understood me. That’s normal. She never set foot outside her neighborhood, never traveled beyond this clump of houses. So, Edena, the S’fars, light years, the distant stars, Einstein-Rosen bridges, all that is beyond her. But it’s true that I’m thin and bald, that my nails have grown so much they look like claws. That makes it all the easier to play the strings of the Large Harp-Lute of Transformations, the sound is more metallic, more defined, closer to the sound that would be produced by a real S’far. All I feed on now is sounds. I can’t remember when I last ate. In any case, I no longer feel hungry.

It’s been raining non-stop for the past month. That’s unusual. Our planet has been experiencing droughts for years. It doesn’t matter. As long as I can work on my instrument in peace and quiet. All I think of is Edena, its suffocating heat, its life. Here, on Earth, everything is sanitized, controlled, conditioned. Perhaps this diluvian rain that keeps falling without stop is a gift to wash away our errors, dilute the emotional drought that has spread across the entire planet. So that we can start over again at zero. A major cleansing. Water! Water! I can’t help but think of the Flood. This building looks like Noah’s ark.

Am I some kind of Noah?

This morning, the H’la almost got free from my hands. Earth shook more than usual. Gaia is angry. She’s fed up with us. I’ve had enough as well. I’d like to leave, to go back to Edena and its colony nestled in the heart of the forest. And, above all, its inhabitants, its sentient creatures, its musicians. It would be an honor for me to play the harp-lute in the clearing, in front of all the S’fars. I’d give my life for just a moment. A moment that would be worth its weight in gold and harmonics, compared to an entire life of smallness, weakness, mediocrity. I envy the musician who sacrificed himself that evening. His destiny was tragic, of course, but brilliant.

I called the Commission to get news about my project. But there seems to be some problem with interspatial communications. Beyond the gateway, there’s nothing but radio silence. We’ve lost contact with our carriers and the colonists. It would be easy to believe they’ve vanished into thin air. Now, that’s annoying.

And my response? And my reservation? It’s big and beautiful in my mind’s eye. Maybe it could be named after me?

If no one responds, how will I be able to go back there? I’m starting to feel frightened. So, I play, for hours and hours, without pausing, without breathing, sleeping or eating. I’m close to the harmonic perfection to which I aspire. Just a few more adjustments, a few turns of well-adjusted pegs. The ground, which shakes without stopping, complicates the final stage in the tuning process. I attach myself to the couch to the best of my ability. It’s like being on a ship in the middle of a storm. It lists, tosses, pitches. The furniture dances, objects spin in a wild dance around me. On the wall, just behind the glass display unit, a crack has appeared. That’s strange. The material used in the building is supposed to be indestructible.

From time to time, I still catch the news, when it isn’t brutally interrupted: dams are breaking, the sea is rising everywhere, tsunamis are ravaging the coasts and pushing farther and farther inland. Entire islands have disappeared!

This was supposed to happen. It’s the natural order of things. Earth has long experienced many major climatic crises and always managed to survive. What’s the point in worrying? I’m staggered by the speed at which people panic. At least now no one has time to worry about me. I receive no messages from my wife, nor from my friends or my children. I would have liked to wish Leonore happy birthday. Six years old already! Where did all those years go? No doubt they’re sealed away somewhere like larva, waiting for the situation to improve.

I’m alone with my instrument. Alone as I’ve always wanted to be.

Water pounds the windows. It’s almost as if the rain is beating down on the city horizontally. Down below, where there used to be a street packed with people, a river flows. It carries objects of all kinds: store displays, garbage cans, vehicles. I think I’ve even seen a few bodies.

Tsunamis, earthquakes, tsunamis. Our Earth is thirsty.

I no longer catch the news. All broadcasts stopped a long time ago. The public lighting no longer works. I live in the shadow, barely brightened by our Moon, which floats, round and high, above the city.

I don’t care. I’ve almost reached my goal.

This evening I’ll get there, I’ll draw the sound from my instrument…

Just one minor adjustment. One minor adjustment that’s not important at all, an ultimate variation in frequency, and everything will be fine.

… the Perfect Chord.

It will leap from the strings of the H’la, the Harp-Lute of Transformations, rise in the dark living room, fill the damp air, fly over the city and its suburbs, mingle with the water that has returned to a wild state. It will be a baptism of sound, colors, shapes, sensations, like those I received on Edena during the transfer ceremony.

Then, a new world will start. A world transformed thanks to me.

I understand now. The H’la has only one master.

It plays only for me.

For me alone.

Laurence Suhner is a Swiss science fiction novelist. She is the author of QuanTika, a trilogy that stages the encounter between humans and an ancient stellar civilization, which has left mysterious remnants on a frozen telluric exoplanet. Fond of quantum physics and astrophysics, she loves to collaborate with scientists to create realistic imaginary worlds as depicted in hard science fiction. Before working as a writer, scriptwriter and illustrator, she studied Egyptology, anthropology, English literature and, more recently, 3D computer graphics. She currently teaches comics, script writing and creative writing at the University of Geneva and in a Swiss special effects and virtual reality school.

With undergraduate and graduate degrees in translation from the Université de Montréal and a doctorate in interdisciplinary studies from Concordia University, Sheryl Curtis is a professional translator living in Canada. Her translations have appeared in InterZone, Galaxy’s Edge, Year’s Best SF4, the SFWA European Hall of Fame, Expiration Date, The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror 15, various Tesseracts anthologies, and elsewhere.