Venus

Dada

Here, here

Whoopee

Nanny

Boobies.

She had the biggest boobies in the world, the longest hair in town and an enormous beauty spot under her left eye.

Almost a third eye and even then, she was nearsighted.

We called her Dada I don’t know why

Well, yes

Yes, of course: because her face

went blah

blah, no esthetics.

One day me and my sister put makeup on her—

Mama’s expensive makeup. Mama was furious.

Commoners don’t have the right to Dior.

I really liked my Dada with big boobies

With her, I watched porn for the first time

We drank Cola, we laughed, we went Oh!

In reality her name was Zohra,

Just like the planet

Venus

My Dada with big boobies

Who is no longer here, here

No, no.

Untitled

I roll kefta balls between my palms. I roll a dead animal between my palms. I role the inside of a dead animal between my hands. I roll the death of an animal between my hands.

I roll death. I roll the interior of a dead animal with the exterior of a live animal.

a) With this death, I will feed my child. I feed death to my child, who transforms it into life, grows through eating death. Children are machines for transforming death into life. For transforming life into death into death into life. Who wins from life or death—

Win what, is it about winning—

b) The odor of this meat is strong. I wonder if I smell the same inside. The deepest I’ve been inside myself is the length of my middle finger. Into my mouth and into my pussy.

Mistaken is the one who says we only have one life (and I’m not talking about reincarnation).

Translator’s Note:

Rim Battal is a French-Moroccan poet I accidentally stumbled across in a collection of essays entitled Lettres aux jeunes poétesses, a spin-off of Letters to a Yong Poet but addressed to women and non-binary aspiring writers. Her letter was unashamedly brave, full of music and raw emotion. I knew right away that her poetry, and her approach to practice, could potentially teach me many things about form and music.

In these two poems, one on childhood and the other on motherhood, we are invited into a world where small details are the most intimate, and violence is simultaneously present and hidden. When I embarked upon translating them, I realized how many risks she takes within strict French poetry conventions. She challenges the most well-known forms of French verse, employing more casual rhyme schemes and wordplay than the revered 12-syllable alexadrines used by Rimbaud or Baudelaire. This gave me the liberty to pay more attention to the weight of the words and the line breaks instead of the rhythm, as Battal’s poetry approaches prose-poetry in its music.

I also found a certain crudeness in her poetry that gave me the space, in my translation, to use words like “blah,” “boobies,” or “pussy,” to think less about the poem as a sacred form of pure language and more as a means to explore human experience and all its macabre, gritty, natural aspects. Especially in untitled, I removed many articles after finding the directness a sharper way of communicating this quality of her poetry in English.

The speakers in Battal’s poems address the body, womanhood, and motherhood in a way that hides nothing and that made me feel less alone as someone raised as a woman. From putting makeup on the babysitter like a doll, to reflecting about how to keep children alive we must feed them death, the poems speak honestly about female empowerment and struggles. They exhibit an unstoppable pride in their contradictions.

I challenged myself to step beyond what I consider as traditional English poetics in translating her work. I stopped trying to be “pretty,” I followed the childishness of the sounds of the words and embraced the sometimes clumsy line breaks. In doing so, I hope to help readers discover Rim Battal’s potential to inspire us all, young poets and beyond.

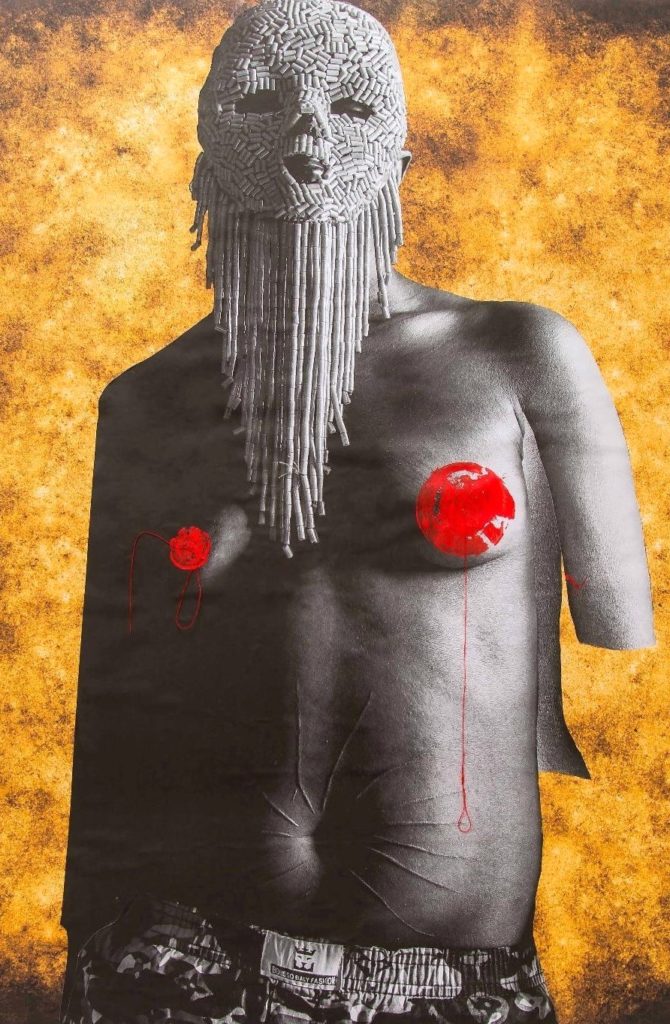

Rim Battal, born 1987, is a Moroccan artist and poet who lives between Paris and Marrakech. Her most recent poetry collection, Les quatrains de l’all inclusive, was published by Le Castor Astral in 2020. Other collections include Vingt pòemes et des poussières (LansKine, 2015) and L’eau du bain (Supernova, 2019). Her photography has been shown internationally, including individual shows at the Galerie Verdeau in Paris and the Voice Gallery in Marrakech in 2019. Photo by Dorothee Sarah.

Ella Bartlett (they/them) is an Iowan-born, New York-educated, Paris-based writer and translator. The recipient of the Gigantic Sequins Poetry Award of 2021, judged by Arisa White, Ella’s work has been published, among others, in Jet Fuel Review, decomP Magazine, Necessary Fiction, and Rust + Moth. Their debut translation, a collection of poetry by opera singer Elodie Kimmel, was published in May 2022. For more, follow @EllatheRewriter. Photo by Lea Volta Photographie.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE