Two in the street

as a finale he threw a chair into the middle of the dive,

he wanted to throw two, but they held him down.

it was a cheesy, faceless dive, a Pepsi-ad color eclectic poverty,

at dawn blue and shit colored flowers bloom at the edge of the city.

of course, they were standing on their two legs pushing each other the way they played with their dump-trucks, ragdolls and pillow cases in their childhood, and later with the thrown out clothes of their lovers.

but now they are in the Villonesque loathsomeness, ready to steal and destroy.

at night they eat the moon, fried eggs they say, it’s enough for them.

fuck reality but mix the moon with hard liquor.

street smelling incense, mint cigarette that they bite, tear and rip

they cannot compare the stars, become uneasy, start scratching,

the stars are scratched out pimples on our bodies they say, and calm down a bit.

they sit in a box at Gajdos’, feeling cold already gobbled the moon up, need something solid.

they stand up swaying like trees in the wind, they’re bony, their skins hang on them like stretched t-shirts, yet it’s starry they say then drop, their skin turns to urine and vomit like gooey substance.

they have their own table in their dreams, they’re free to take.

their blouse and shirts are ironed, their jeans are clean, their shoes are shining

there is a roof above their heads, simple small rooms and everyone minds their own business, things only they know, aren’t drunk, clinking their tall glasses

because there is some kind of holiday or other good happening or just because.

two persons in the street, both easily transplantable, lie on a kind of asphalt rug

going wild like grown children and know that they are only similes and metaphors.

they get up, cut the throat of reality, get disguised,

walk in blue and shit colored eclectic poverty, in the gypsy row, and then they put all of it in writing.

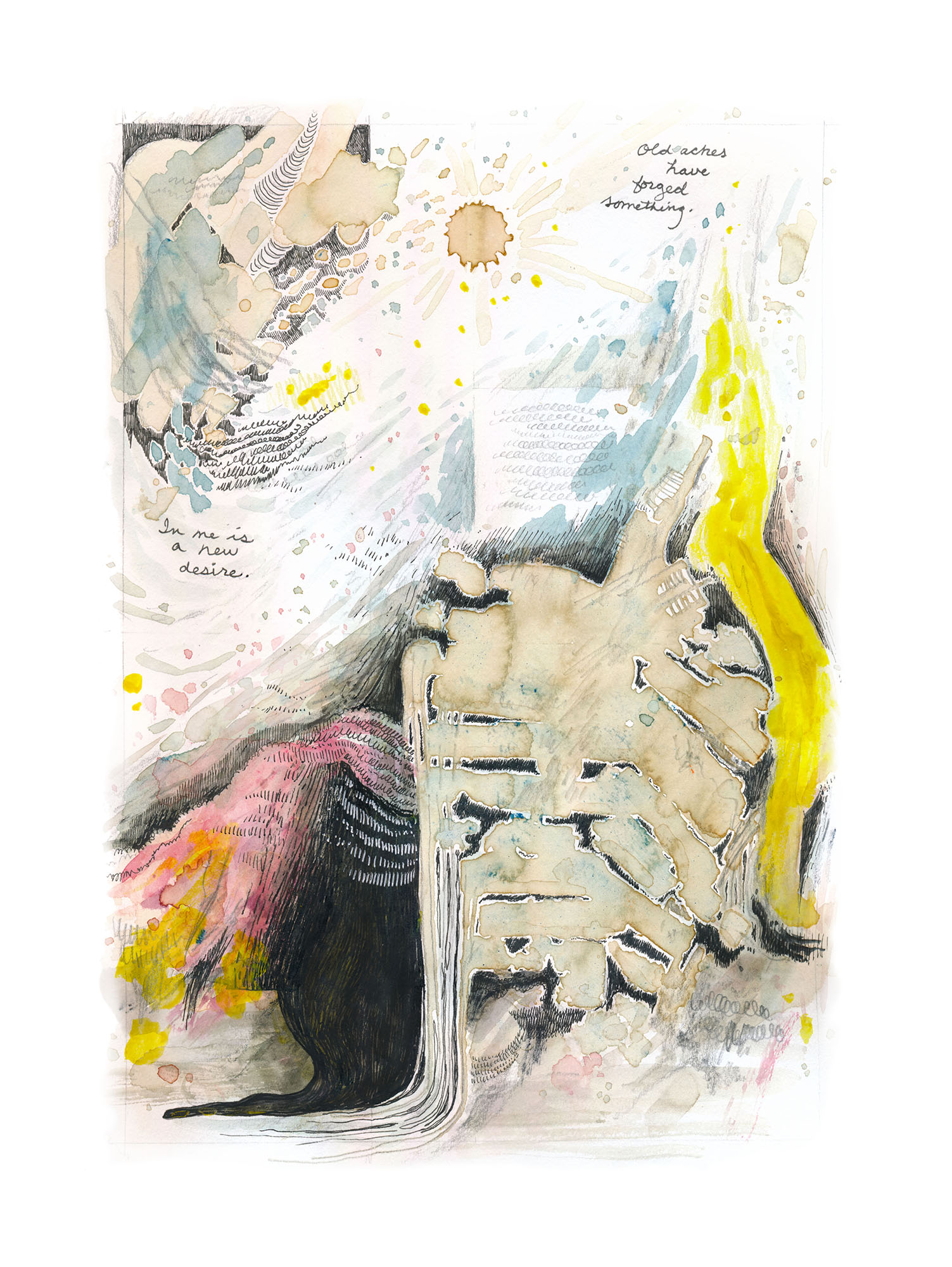

immortality

dad is a shell

mom is a fuzzy heart root

when the rain comes, we drench together

when the sun shines we are together

in the light

sometimes I bury them in the woods

to save them from trouble

I call them to hold hands and

whisper into each other’s ears

dad and mom are whispering

earth is guarding them

we practice resurrection

they come out of the ground

wash their bodies

dress up and go to work

they call me Sunday saying

lunch is ready for Wednesday

they ask if I have anything to eat

then I invite them to the woods again

they say it’s awkward for them

but they will do it if I want to

Translators’ note:

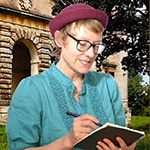

Zsuka Nagy’s idiosyncrasy is apparent in her free verse, where form is determined by the dynamics of strong emotions, lightened by a whimsical rhyme here and there. Her poems stand out for their bravery and vocabulary, even in a contemporary environment with fewer taboos, and for their unflinching take on the great themes: love, family, illness, poverty, rural life, old age, and death. A major motif in her work is the attention given to people living on the periphery of the mainstream. Her poems are at once intense and gentle, sometimes coarse, mixing everyday speech with lyrical imagery. Pigment, her third and most recent book of poetry, was published in 2018.

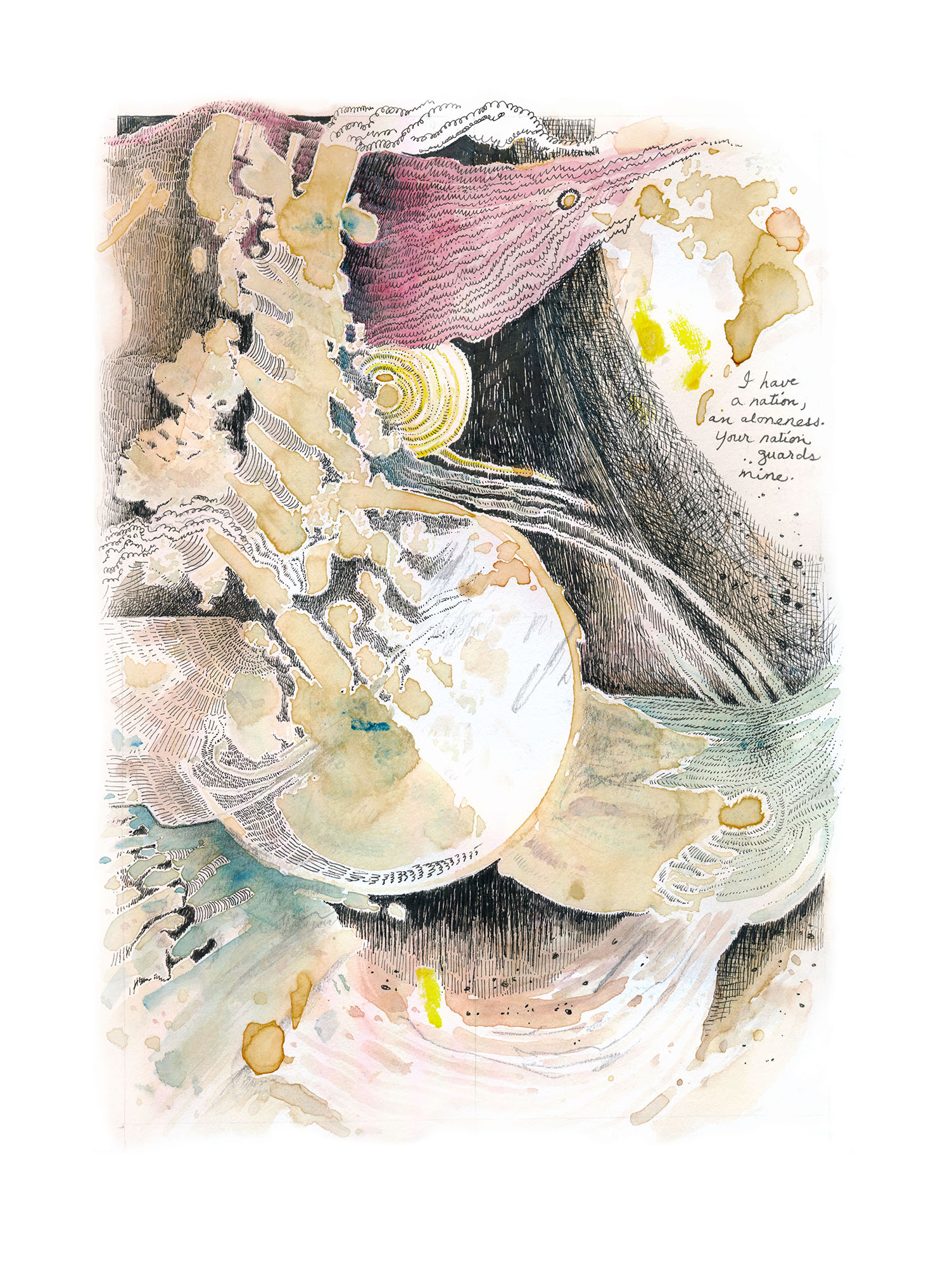

Terri Carrion was conceived in Venezuela and born in New York to a Galician mother and Cuban father. Her work has appeared and disappeared in print and online. She is co-founder of the global grassroots movement 100 Thousand Poets for Change.

Gabor G Gyukics, a poet and translator from Budapest, is the author of eleven books of original poetry; six in Hungarian, two in English, one in Arabic, one in Bulgarian, one in Czech. He is the translator of eleven books including A Transparent Lion, selected poetry of Attila József, and Swimming in the Ground: Contemporary Hungarian Poetry (in English, both with co-translator Michael Castro) and an anthology of North American Indigenous poets translated into Hungarian under the title Medvefelhő a város felett.

Zsuka Nagy was born in 1977 in Nyíregyháza, Hungary and is a poet, writer, teacher, and the author of four collections of poetry. She lives and works as a teacher in Nyíregyháza. She likes poetic images just as she likes riding her bicycle which she calls Rozi. She is the recipient of several prizes.

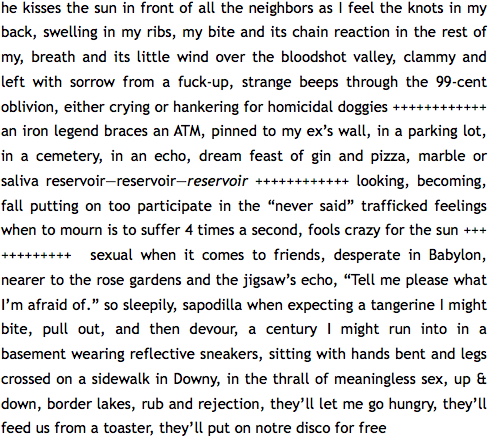

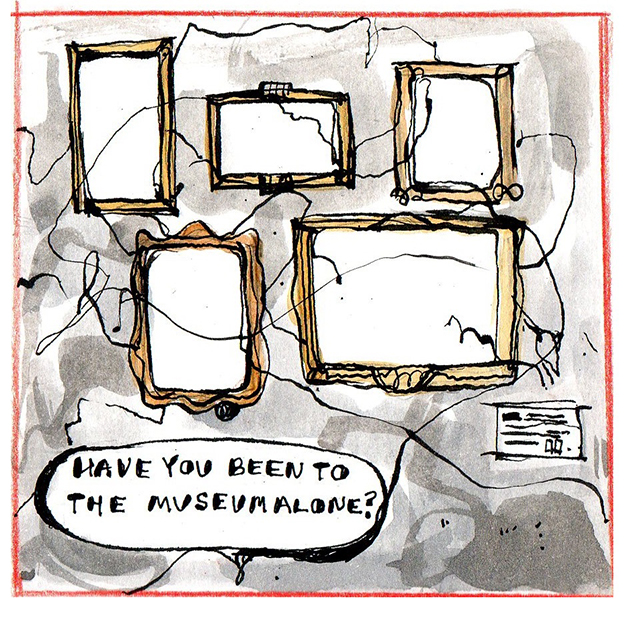

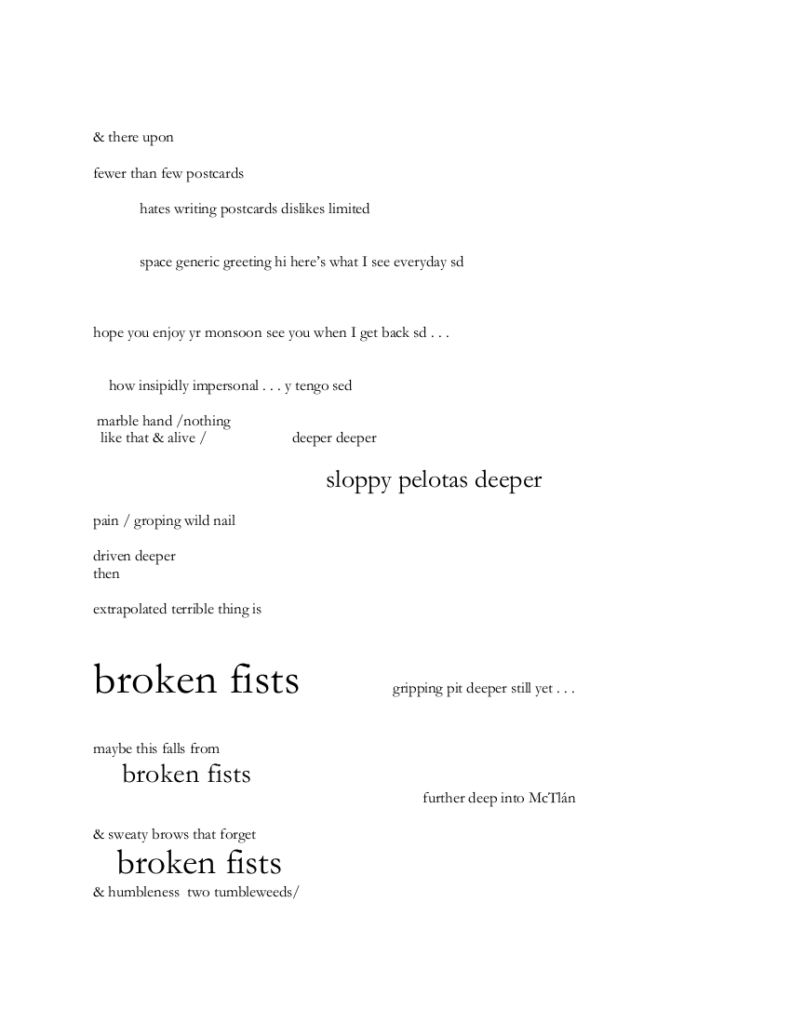

![Pancho EL PRIMERO / to La Marcaida / Sinaloa // think I smell you / taste yr eyes / dream yr brown hands / groping a map of Tetaroba / open my eyes / see yrs still closed / kiss yr lids w/ thoughts untied / yet only the deepness inside me knows-- / missing the smoothness of yr warm neck / bids me to forget me in you more / fingers opening as roses & sudden / images descending / countries reathing / winds rise / hear yr breath / you breathe: tight (& writhe) / exhale / & my stomach shakes / paint any monstrosities you want / jellybean / poets all the same / words no action / ¿ow to speak? / wish w/ pages of boulders // yes Pancho EL PRIMERO / to La Marcaida / owned by the State / decidedly chose to write // machines speak loudly / definitively // call me call me call me Pancho ordered himself to follow / his desiring destined bones / toward the nude whose back / [margin: La Malinche] / faced his front / entered her / vigorously pumped / dispatched / thoroughly woke her / though considering / nothing else / she woked / turned her glance-- / seemingly expressed a kiss // Pancho dismissed this because a priori his breath / reeked open-mouth sleep / even worse as he sleeps w/ his mouth open // Pancho cd write / wrote/ read / sometimes instead / cloudpiles / hear train choo chaos desmadre / sun shines / clouds run / the blue blue blue / kind can't stand divided / MS letter holdings of Pancho Chastitellez estate / 19 Jun 2000 // Chaley to Pancho // see Olson: recognizing that writing & geometry are always entwined / connected // shapes of letters reflect cultural notions of spatiality / Euclidian space in our letters we inherit mostly from Greece by way of Rome / don't write boustrophedon / nor hieroglyphically / y liverty y susto for algunos // el conquistador es la figura que domina la historia de los años iniciales del contacto hispano-indigena/ y el conflicto dominante es el desequilibrio de la Antigua sociedad prehispánica sometida a un NUEVO ESTADO de cosass-- // PHYSICAL ENJOYMENT Tío / ¡Ay! reason Chastiteyes: / both reality & process how to operate / yes // nothin I cd be / trope / creature from second stage of-- / no more than s-some creature crowing / over own triumph over incoherence // heard this from una ruca cryin / cryin / cryin: // que ya te crees tanto . . . tú eres de Amurika / ya sabes hablar ingles y todo eso // think abt Quetzalcoatl / my true conquistador / is that it helps me / take my mind / off things by / doin something w/ me / sometimes my sweet conquistador / promises that we will do something / & then we don't do it / my gentle conquistador makes fun of me / in ways that I don't like / I wish my darling conquistador wuz different / O BUT WHEN I AM . . . / when I am w/ my adequate conquistador / I feel disappointed / & when I am w/ my antigovernment conquistador / I feel ignored / & when I am w/ my reformed conquistador / I feel bored / & when I am w/ my symbolic conquistador / I feel mad / & I feel that I can't trust my habitual conquistador / w/ secrets b/c I'm afraid my feigning conquistador / wd tell my parent/guardian / & when my abnormal conquistador / gives me advice / my soft conquistador makes me feel / kind of stupid & ashamed / I wish my parliamentary conquistador / asked me more abt what I think / I wish my necessary conquistador / knew me better / I wish my loathsome conquistador / spent more time / w/ me](https://anmly.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Pancho-El-Primero.png)

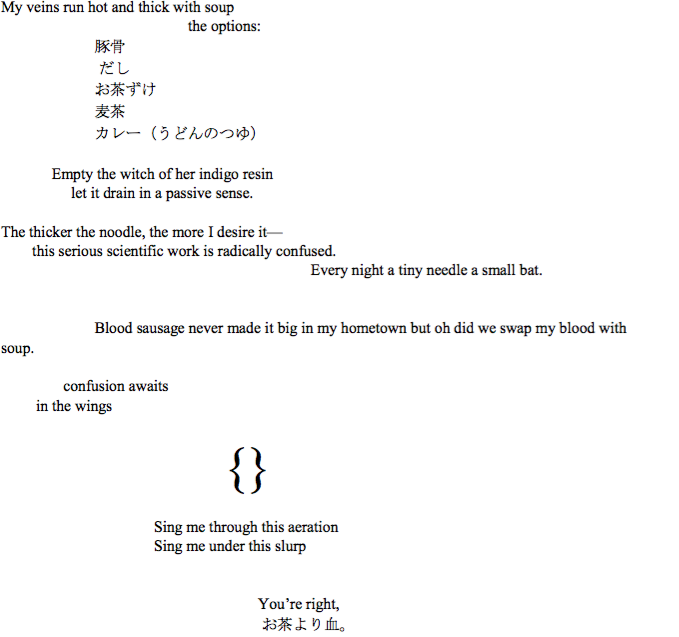

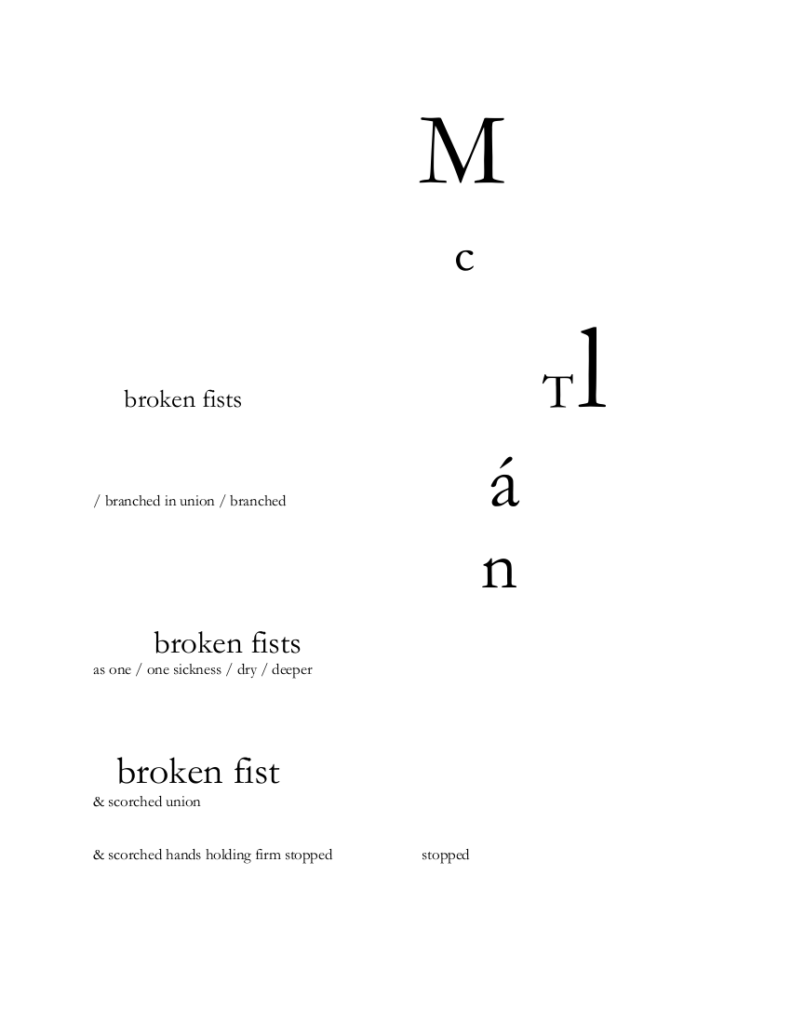

![ENTER CAVE | | . . . in the beginning was the DEAD . . . | | McTlán / al Norte / AZtlán | vivid [sic] desert / sand / heat / vacancy | “no eres betwixt or between cabrón | “brace yrself coz I’m the Mex next to más | “& images flicker & pass pos: | “mucho maas deeper pues . . . | “¿ye want carnitas ? / ye’d better respect my aGuad-loop ¿eh? | “¿ye don’t respect her? / & I’ll send ye right to yr ma . . . dray” |](https://anmly.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ENTER-CAVE_page_1-791x1024.png)

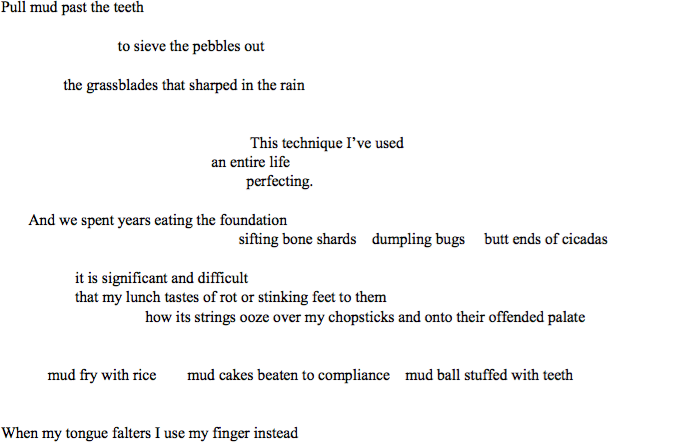

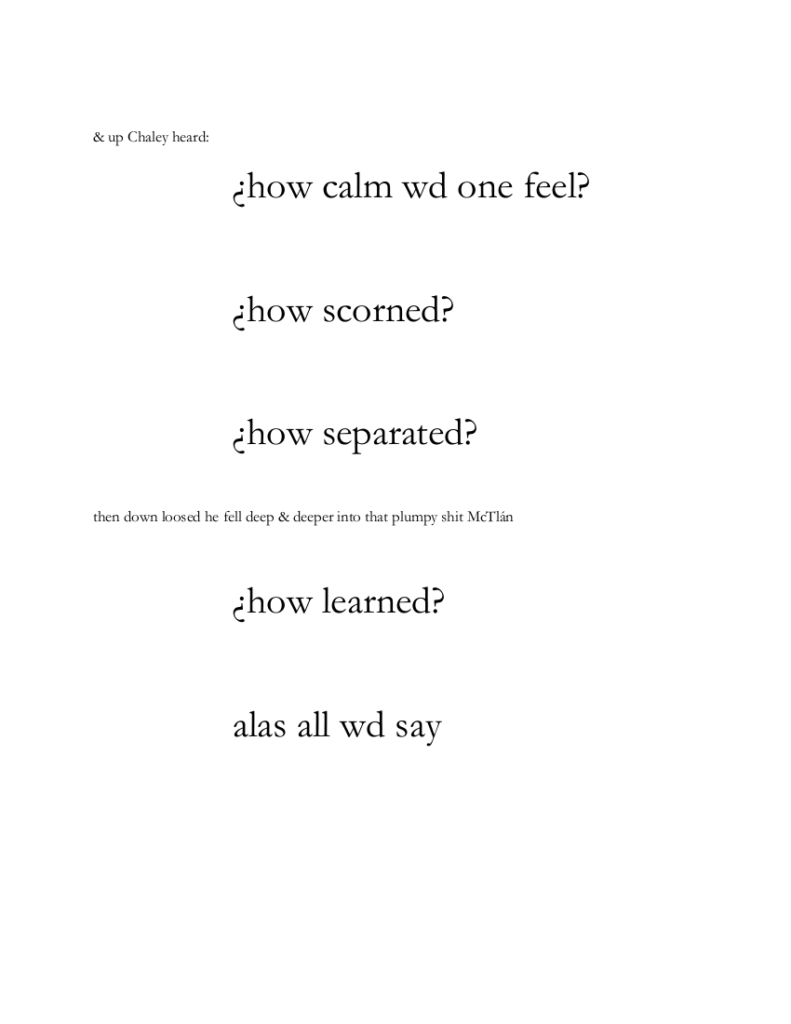

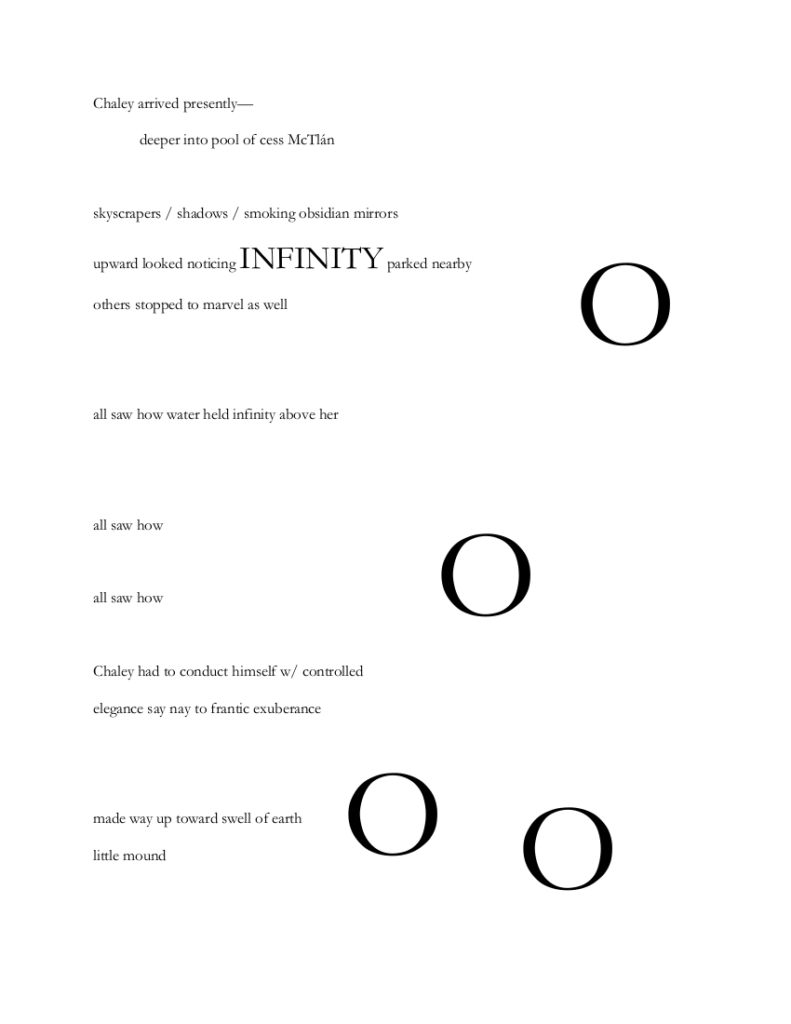

![into nothing | nothing [double struckthrough] | before arriving in | McTlán | aL | nORTE | AZtlán | dismay | dismay general no dismay O | O |](https://anmly.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ENTER-CAVE_page_6-791x1024.png)

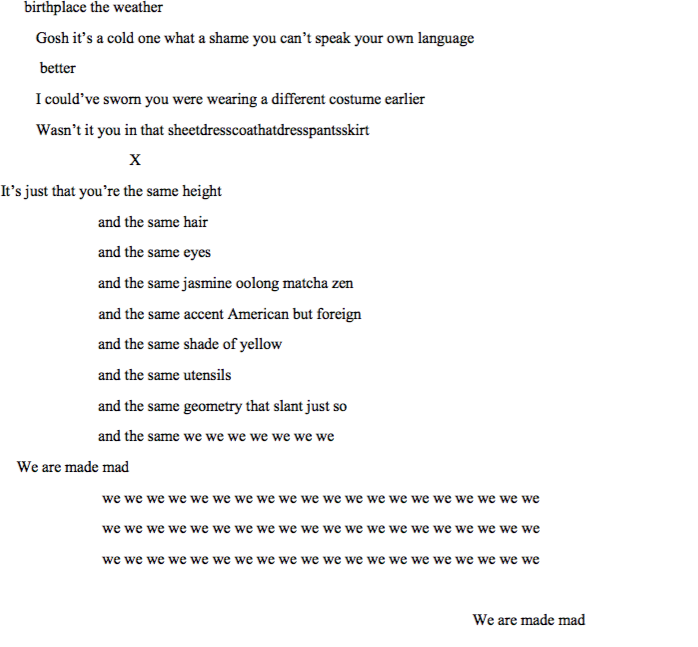

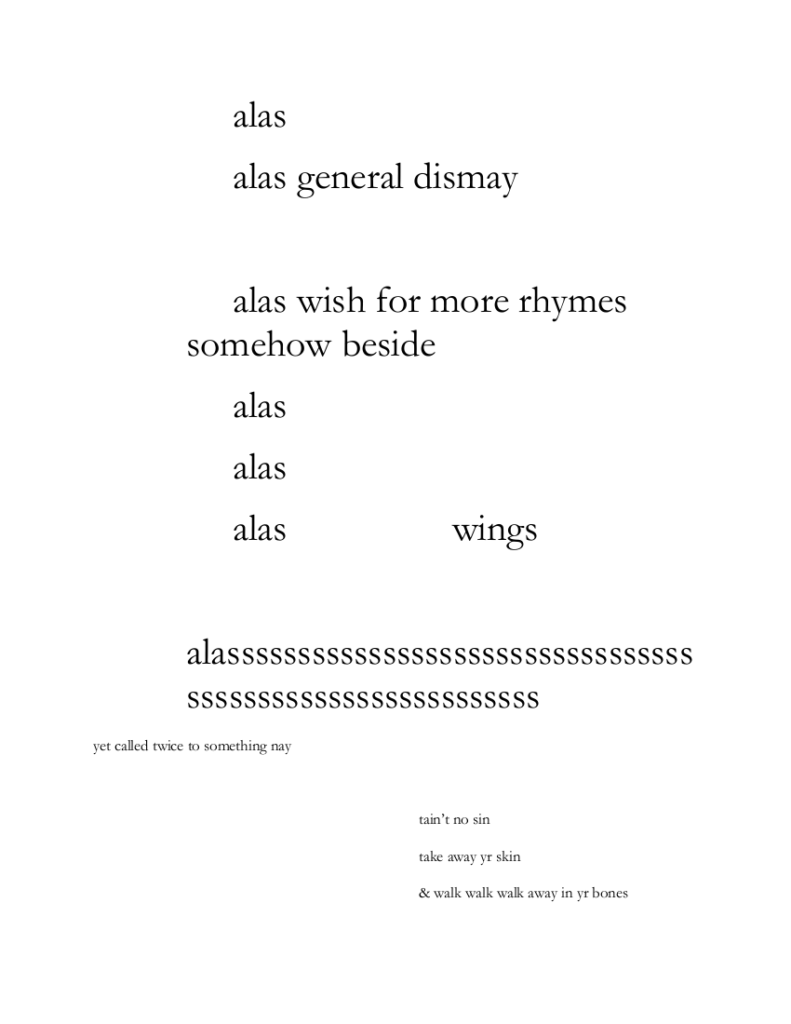

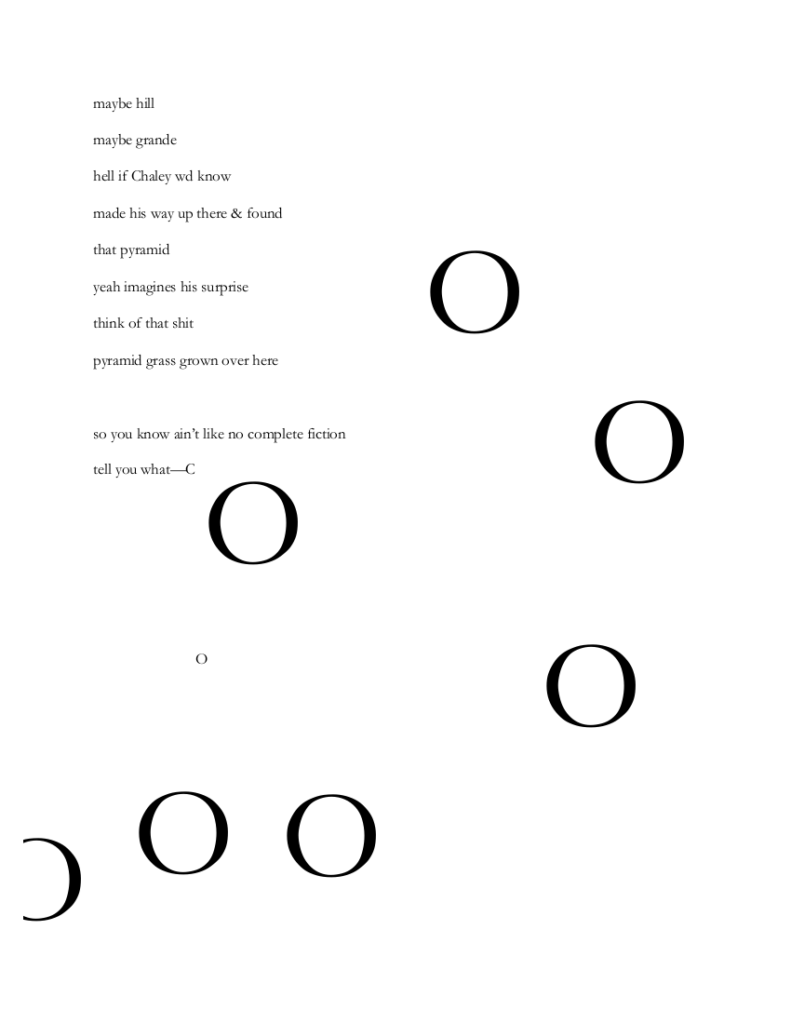

![OO | O | O | O [double struckthrough] | O | O O | O | O |](https://anmly.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ENTER-CAVE_page_9-791x1024.png)

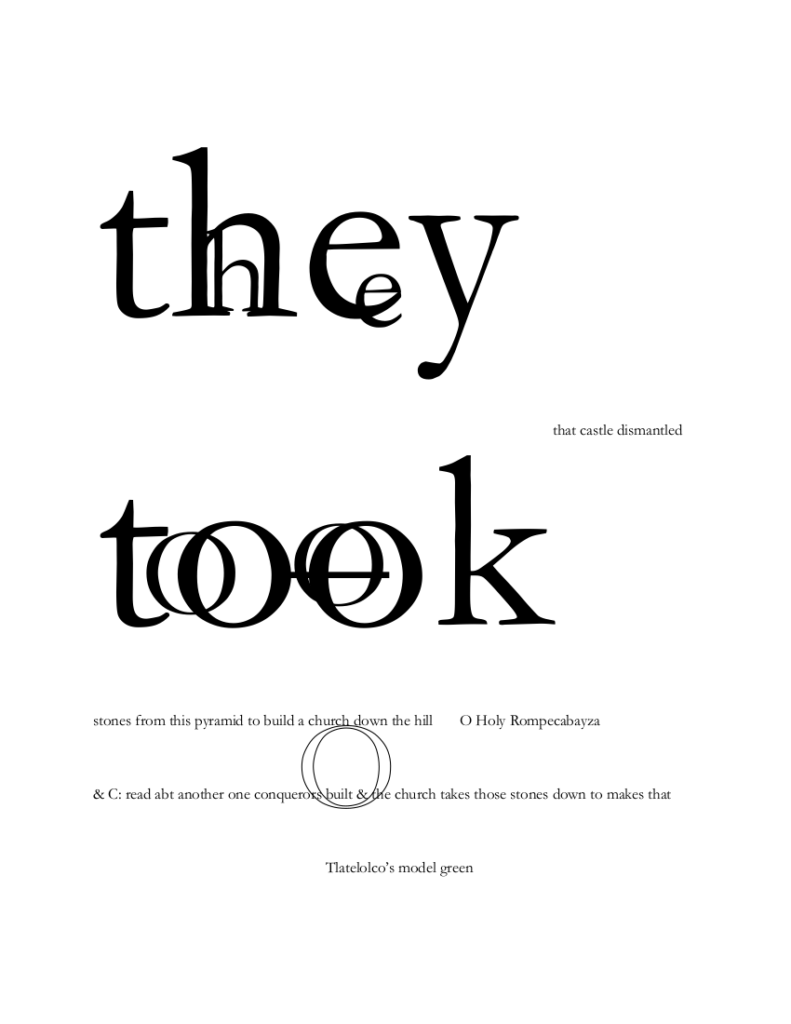

![O O | soundtrack & lesson this like | ¿asking for a goddamned lesson? | M c T l á n ’ s p l e a s u r e s | give me a lesson & we’re waiting—two demons platicando | ¿waiting for who? | looking at one another / away / | & A HUEVO GÜEY—away | fase uno: waiting to become / human dead / ¿zombies then? | fase dos: stacked ourselves w/ wit ¿what part | of illegal don’t ye understand beaner? | for these demons nothing but living dead exMexes | & indeed upon inspection w/ exes in their eyes | ¿we’re what? | waiting | simultaneous: | waiting to go [double struckthrough] | home [double struckthrough]](https://anmly.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ENTER-CAVE_page_11-791x1024.png)

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE