Idols

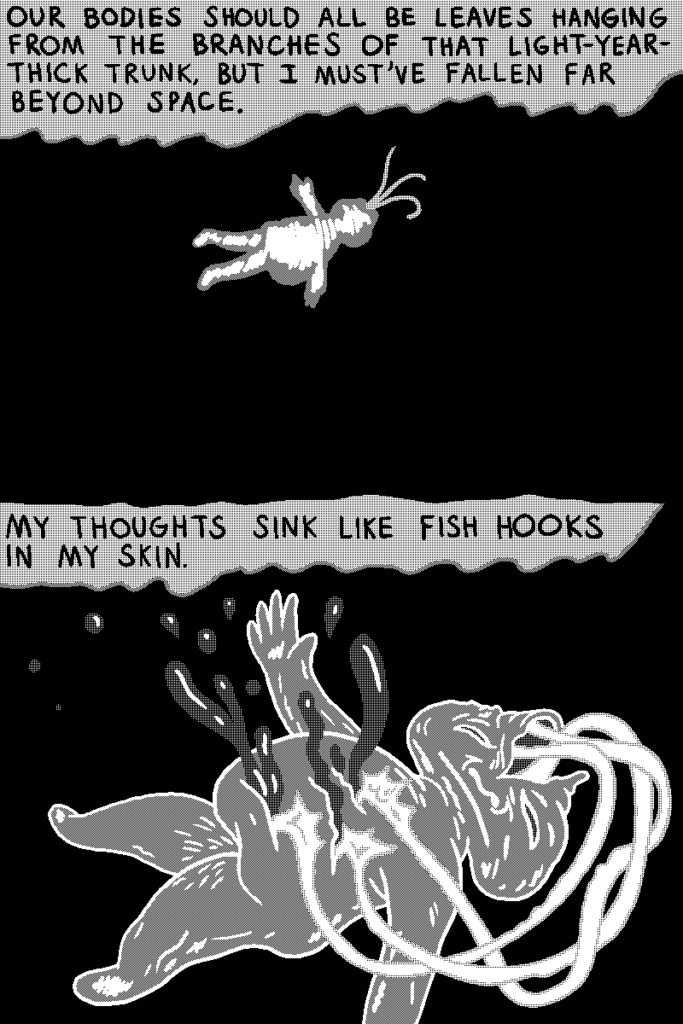

Perfect Blue (1997), a film by Satoshi Kon

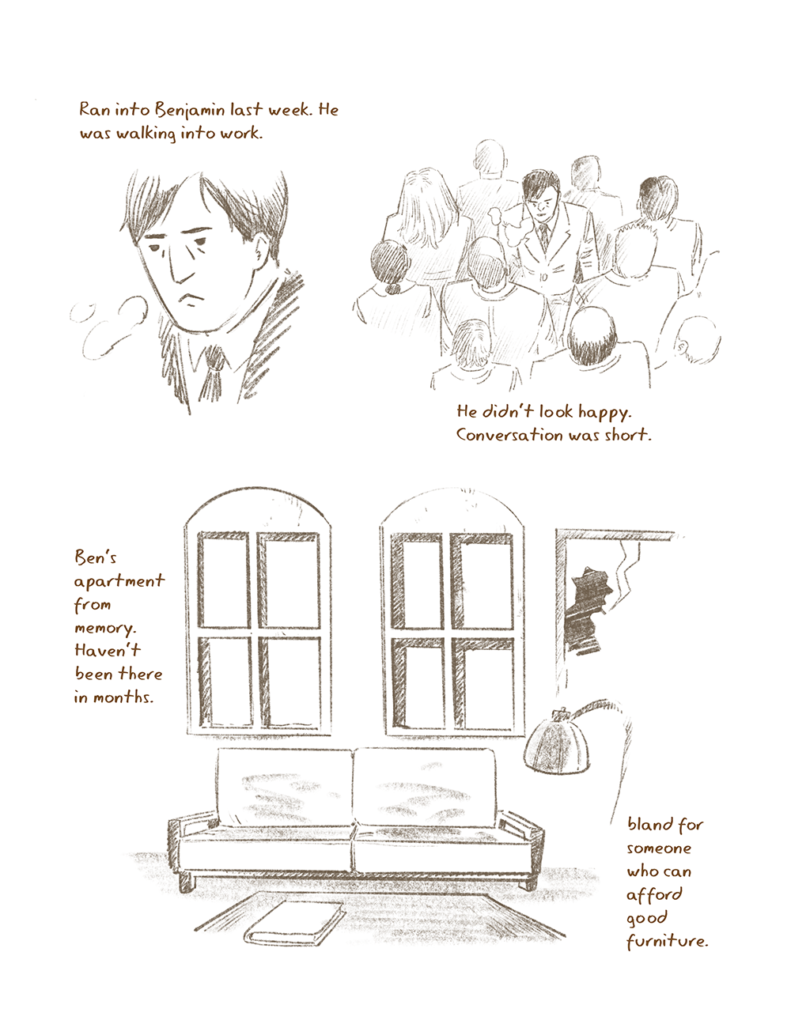

These women who perform as idols, who feel like friends, enter the stage. The white ribbons on their bare shoulders and the pink of their crinoline skirts flutter as they dance and sing.

These women who perform as idols are ballerinas— I mean, schoolgirls—I mean, Sailor Scouts—

Do they know that this audience of exclusively men—and me—have a soft spot for women who wear bows in their hair, who smile with enthusiasm?

These women who perform as girls dance in perfect unison, crooning their siren song: Look! Can you see her white wings? Those eyes gazing at you. That sweet voice, and those gentle hands. They exist only for you.

All the men are watching and some of the men are taking photos and some of the other men are holding camcorders, recording every breath and every twirl.

I’m no better than these sallow, indoor-skinned men—just more beautiful—After all, don’t I have an affinity for small hands too? Doesn’t the fire in my body long to know the fire in theirs too?

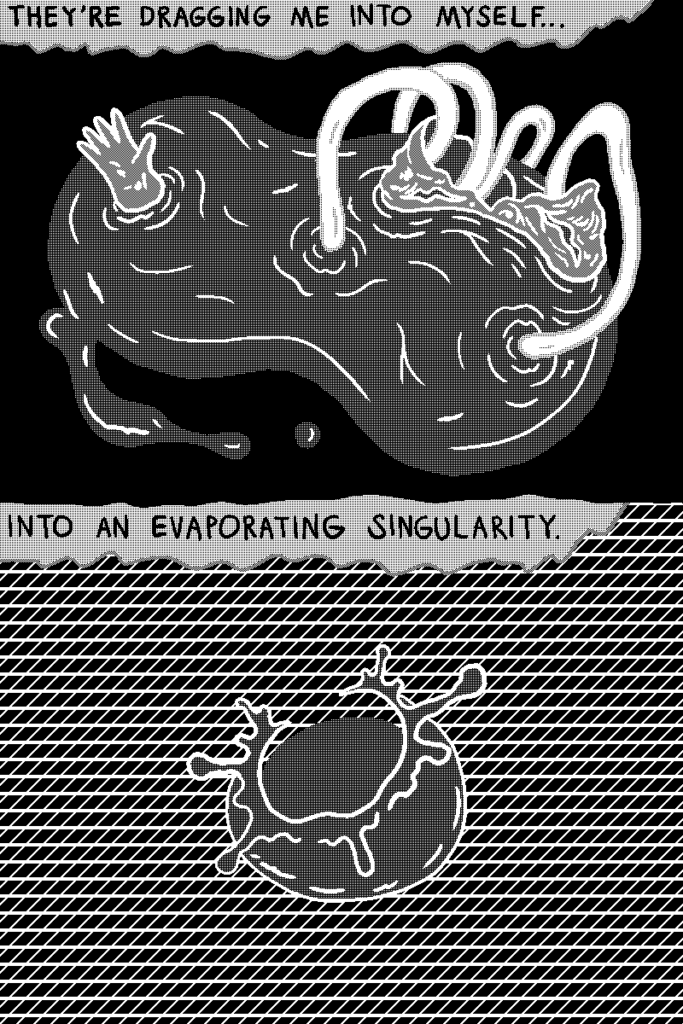

Simulation

Perfect Blue (1997), a film by Satoshi Kon

The actor says I’m sorry before the scene begins.

The actress smiles a dazzling smile and says It’s okay.

A camera crew surrounds them. The flashing lights are relentless.

The director yells Action and it begins. He towers over her. Her body flails.

The director yells Cut and it stops. He towers over her. Her body lays limp.

The director yells Action and it begins. He towers over her. Her body flails.

The director yells Cut and it stops. He towers over her. Her body lays limp.

The director yells Action and it begins. He towers over her. Her body flails.

The director yells Cut and it stops. He towers over her. Her body lays limp.

The director yells Action and it begins. He towers over her. Her body flails.

The director yells Cut and it stops. He towers over her. Her body lays limp.

The director yells Action and it begins. He towers over her. Her body flails.

The director yells Cut and it stops. He towers over her. Her body lays limp.

The director says It’s a wrap. She puts her clothes back on and goes home quietly.

At night, when she believes nobody’s watching, the actress cries over her dead fish still floating in the fish tank. She thought about the camera crew, her management team, the writers, the producers, the directors, the other actors. People always talk about speaking up as though it’s obvious. She couldn’t think about herself. She tears her soft white comforter apart. She curls into herself.

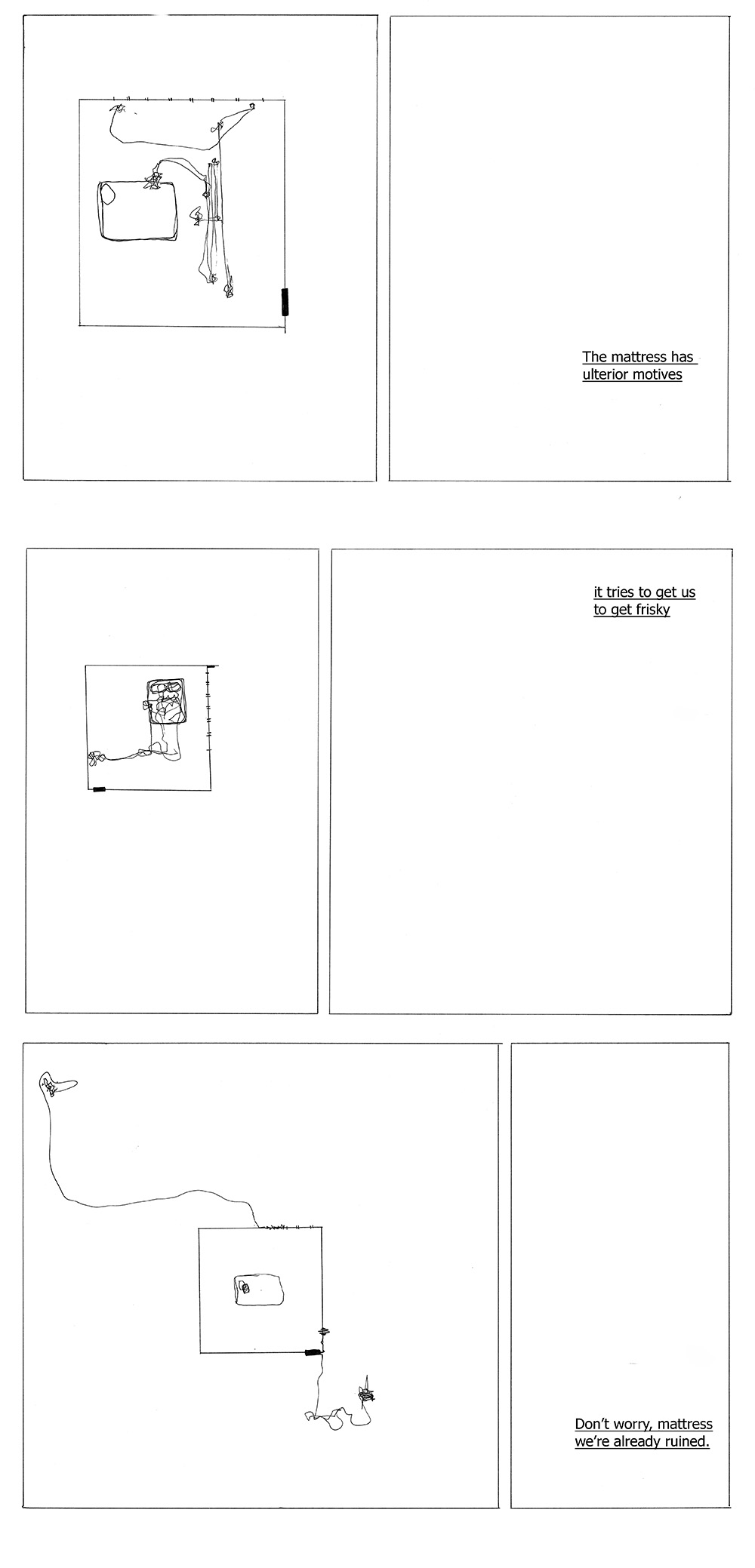

Crying Whilst Listening to 90s Cantopop

I take a Hong Kong Film Class thinking

I’ll meet someone like me

Instead, I meet a bunch of gwai lo

who want to fuck Faye Wong.

/ /

We watch 2046. Wong Faye plays

a broken robot train attendant—

Her functions have been exhausted

from overwork and thus, her emotional

expressions are often delayed.

Still, men love her—or at least, what she represents.

She stares at her reflection in the train window.

Her doe eyes. Imprinted onto my mind.

/ /

I sob through every movie that quarter,

even Rumble in the Bronx

which seems to confuse a classmate

though it doesn’t stop him from hitting on me.

What disturbs me the most is me

I’m flattered by his inquiry.

/ /

I look up reviews for Infernal Affairs

One of them says The Departed is superior,

because despite being a copy, at least it has soul.

/ /

On Youtube, I watch some Mandarin bitches

stumble their way through Leslie Cheung’s

“Love Of the Past” from A Better Tomorrow

and I seethe with jealousy—My accent is perfect,

according to my mom, but I cannot read so I will never

Cheung K in the way that my ancestors want me to.

/ /

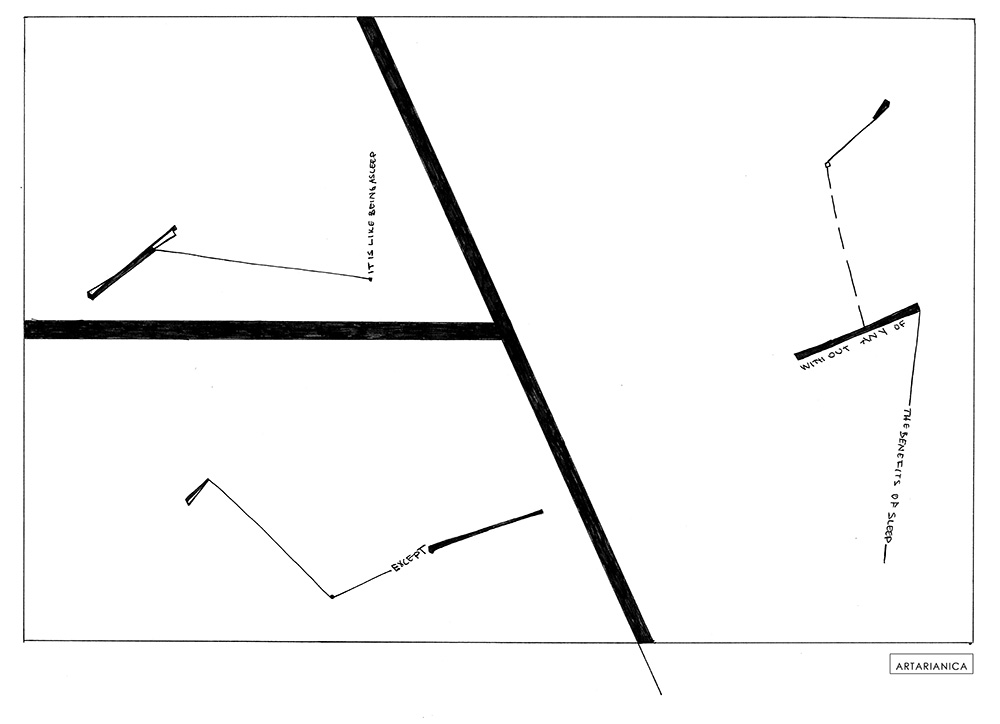

My favorite Wong Faye song is a Mandarin song.

It’s called 悶 which means bored or depressed.

悶 is 心 (heart) with 門 (door) surrounding it.

Depression or boredom is when something,

such as a door, has closed on your heart.

/ /

If Mandarin were skin

it’d be the milky white supple expanse

of a maiden’s midriff

Cantonese is more like

the frizzled plumage of a Silkie chicken

/ /

My research says one should sing to speak in Cantonese:

si ( → ) is poetry

si ( ↗ ) is history (or poop)

si ( → ) is try

si ( ↘ ) is time

si ( ↗ ) is market

si ( → ) is be

/ /

Everybody, including myself, forgets

that English is my Second Language.

“I didn’t learn English until I was five” feels like a lie.

/ /

My parents said we had Aaron Kwok’s

對你愛不完 on cassette and that I loved dancing to it

and that I kept dancing until one day I realized

people could see me and then I stopped.

Listening to 對你愛不完 now,

it sounds familiar

though I can’t tell if I’m unearthing a memory or if it’s just my desire to remember

projected onto a pop song that sounds familiar in the way that all pop songs do.

/ /

You can save space on Apple devices

by offloading memory. This means

deleting an app’s data whilst keeping

any documents or settings tied to it.

Cantonese has been offloaded from me

The texture of the language is still there

and not much else.

Alison Zheng (she/her)’s writing is published or forthcoming in The Margins (Asian American Writers’ Workshop), Black Warrior Review, Copper Nickel, and more. She is a MFA Candidate and Lawrence Ferlinghetti Fellow at University of San Francisco.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE