Changes

She parks her car and walks down the broken pavement, afraid her heels will catch in the cracks. The restaurant is round the next corner, a small, nondescript place on a side road in Mohandisseen. At the lamppost outside the entrance an old peasant man hums to himself, beside his warm batata cart, the waft of his roasted sweet potato fills the void of the chill night.

There’s a clock on the wall: 8:15; on time. The waiter smiles apologetically and asks her if she has a booking. None? There are no tables inside; there is a nice one here on the patio. Fine. It is cold though; could the waiter get a portable heater? Certainly. Would she like to order? Not now. She will wait. She is good at waiting.

The batata vendor is audible from the patio. He begins to sing an unfamiliar song. It sounds made up.

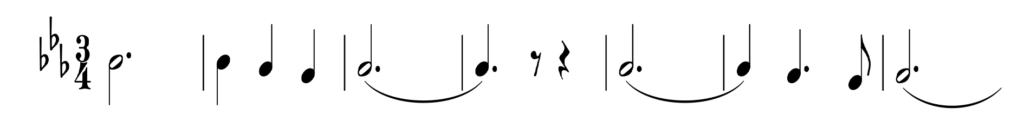

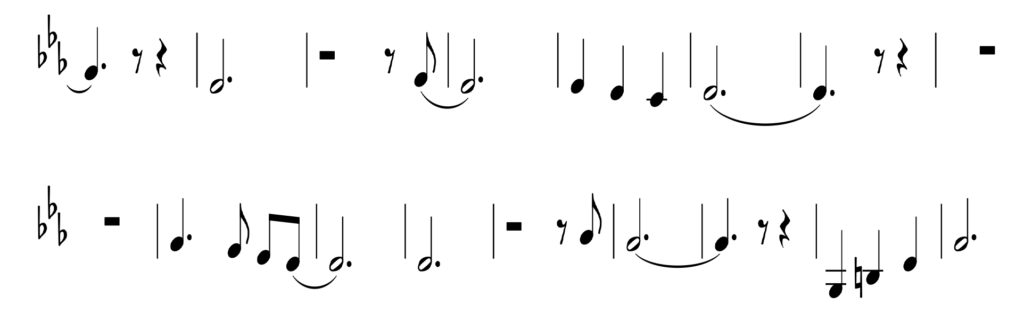

Oh, the ship in the storm yearns the port,

but the port is not what it seems

when the ship returns,

It will not be safe

For it will drown in its dreams

His voice is like scratchy plastic. Why doesn’t the restaurant manager tell him to clear off? He can’t be good for business. She wonders if she did the right thing coming. And why this vague place, an empty vessel, void of memories for them?

Finally he arrives, fifteen minutes later, a great chocolate trench coat carrying a man of purpose. He sweeps onto the patio with ease. He is not late, his footsteps say; he is never late.

He smiles and swoops down as if to kiss her, but instead only clutches her shoulder. He casts off his enormous coat and sits across from her, placing his many blinking, beeping phones on the table. He asks her if she has ordered. No, she was waiting for him. Ah, but she knows what he always ever eats, he reminds her. Well she thought he might like something different. He grimaces, like someone who has just tasted castor oil. Does he ever change his order?

The waiter comes. The man orders briskly for both of them: soup and crackers, salads and main course. Beverages later? They will only fill us up, won’t they, dear?

He links his fingers together and glances across at her. She looks lovely, he says. She gazes down at her reflection in a spoon. She did look very good, so ripe in beauty, the warmth of roast chestnuts on an open fire, stirring in her oval face.

The peasant with the batata cart leans against the patio railings. “Akhenaten! Akhenaten!” he yells. “What was he thinking? He must be insane to imagine he could bring change!”

The man grits his teeth. What, did she not find a table inside? This peasant will give them no peace. Waiter, can you tell him to move? I’m sorry sir, he doesn’t listen, but he never stays long. Then tell him to keep it down. Certainly, sir.

What were they talking about? She tells him nothing yet, so he asks her how she is. It is such a vast question. An ocean. She feels helpless before it. El-hamdulilla she decides to say. And the children? Growing used to their new neighborhood? Making friends? She nods. He jabs at his meat and edges closer. He is proud of her for coming today. He is proud she is willing to start afresh. So this is a new beginning? Yes, yes. It is never too late, is it? No, she says, never too late, as long as people are ready to make it work. Was he prepared for lasting changes? He chews. Well he came here, didn’t he? That proves something. And the other women? Nothing worth mentioning, he assures her; they weren’t even real. So was she real? Of course she was, she was real and she was permanent. A safety net. A safety net? Is that all? To catch him when he fell?

The batata man begins to rant. “Thought he had created a new empire! Tel el-Amarna. Homage to the God Aten, but no! But no!”

He frowns. To be a safety net is a great thing. He would be her safety net, too. So, would he move to their neighborhood, for the children’s sake? Ah but work—she knows how it is! It’s hard in this sprawling city to commute, not convenient for the breadwinner. She ought to move back, she and the children must return to their haven. But how? The children—

—They must sacrifice for the bigger picture.

His phones blink red, and he picks one up to read a message. There’s a meeting in a hotel nearby. It was unexpectedly confirmed, so he needs to get going soon. He would have to sacrifice dessert, but he would pay the cheque before he left. It’s a good thing he chose a restaurant so close or he would be late for his appointment.

“Akhenaton! Dead! A great heritage gone, all disappeared, as if it never happened. The House of Aten torn down. The more things change, the more they stay the same!”

The man rises. He is sorry, he says; it is so important he doesn’t miss this meeting. She looks up at the clock again: 9:15 exactly; hands outstretched, straining across the clock face, like an embrace between parting lovers.

They would meet again soon, he smiled, swiveling away.

“It’s a lie, a lie! Short-lived rebellion! Back to old ways, Aten forgotten!”

She sees him through the railings, flashing an exasperated look at the batata man. What a strange, babbling fool. He presses a five-pound note into the peasant’s palm. The peasant recoils, indignant. “No charity! My sweet potatoes cost money, but I give you my wisdom for free!”

Fatima El-Kalay is a short fiction and poetry writer who was born in Birmingham, UK, to Egyptian parents, but grew up north of the border in idyllic Scotland. She has a Master’s degree in creative writing, and has had short fiction published in Passionfruit (US) and Rowayat (Egypt). Her flash piece Snakepit was recently longlisted for the London Independent Story Prize (LISP). A story anthology The Stains on Her Lips, her collaborative project with two other Egyptian authors, Mariam Shouman, and the late Aida Nasr, is due for publication in summer 2018. She is currently working on her first poetry collection. In the past Fatima wrote healthcare articles for a major parenting magazine in Cairo, over a span of 10 years. Fatima is also a self-taught artist and a self-help coach. She lives in Cairo, Egypt with her husband and children.