A Spell to Invoke the White Dolphin

By Jeon Sam-hye, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur

They were nine years old, that age when the two of them could roll around the living room floor gorging on the Harry Potter series without their mother telling them they had to get to their after-school hagwon crammer.

Jinwoo had suddenly called out, “Hey, Kim Sunwoo.”

Sunwoo, who’d been reading Volume 2 of Book 4, answered, “I told you to call me nuna.”

While it was true they were fraternal twins born minutes apart, Sunwoo never thought of herself as anything less than an “older sister.” But Jinwoo would never call her nuna unless he wanted something from her.

“Sunwoo, what’s your happiest memory?”

“Happy” was a word they still weren’t quite familiar with. Sunwoo closed her book and said, “Why do you want to know?” Jinwoo pushed the volume he was reading towards his sister. “Look. There’s a spell that works only if you think of your happiest memory. So what’s your happiest memory?”

As Sunwoo mulled this over, Jinwoo answered his own question. “For me it was when we were six and we went to the amusement park and Dad bought us those Hot Wheels. We got the same Hot Wheels and we rolled them around in our bedroom and grandma got mad at us. Said we were leaving scratch marks.” Jinwoo snickered, but Sunwoo couldn’t laugh.

Because she had the same memory as her happiest, too.

The reason that was Sunwoo’s happiest memory was not because she got a shiny blue Hot Wheels car or because she went to an amusement park with her father. It was because that was the only time she could remember when she was allowed to have something that she didn’t have to share with her brother. Sunwoo couldn’t buy so much as a puff of cotton candy without her mother telling her to “share it with Jinwoo” when handing over the money. Whenever Sunwoo begged for toys like Hot Wheels or robots, the kind of toys Jinwoo got to play with, her mother and grandmother would put her down by saying, “you’re a girl,” and push her towards dolls or playing house. Her father was the only person in the house who didn’t force a division of Sunwoo and Jinwoo into girl and boy. But, Sunwoo thought with a sigh, that’s not because Dad likes me better or he’s a feminist. Dad is too busy. He’s just too busy to discriminate between us. Sunwoo fortified herself in advance for the inevitable day when even her father would say to her, “Who do you think you are, you’re a girl.”

And if they both conjured up the same memory, what would happen in that spell? Would its power be halved and the spell rendered useless? If that’s how it worked, would she be forced to make yet another concession to Jinwoo?

“Hey Kim Sunwoo, I said, what is your happiest memory?”

At this urging, Sunwoo put on a wan smile. “Doing the Lucky Dip at the stationary store last week and winning an ice cream.”

A lie.

*

I’m glad we were born when we were. That’s what Sunwoo thought whenever she and her twin brother got into one of their “accidents.” She mused, If we were born decades, or even fifteen years ago, the two of us would’ve grown up being bullied as psychics, mentally unstable, or weirdos. We would’ve been put on TV to make a bit of money, or kidnapped into a circus to live out our lives in misery.

Once a writer in England made it known to the world that such powers as the twins had was actually something called “magic,” the two siblings felt they could breathe a little easier. Not that Sunwoo and Jinwoo’s parents, who had bought them the entire Harry Potter series, bothered to even flip open the cover of any of those books. Sunwoo and Jinwoo, on the other hand, pored over these passé bestsellers over and over to the point of memorizing entire passages. They were nine years old at the time. The Harry Potter series, for nine-year-olds, was a little too much to take in completely, but Sunwoo and Jinwoo had one clear takeaway from these books. And that single takeaway was more important than anything else in the series.

Sunwoo and Jinwoo were wizards.

Thanks to this knowledge, they spent each day waiting for their eleventh birthday, which fell on their fifth-grade year, in eager anticipation. Despite their little accidents such as unwittingly making objects float or trees wilt or walls crack, they could confidently put such mistakes behind them in the wait for their eleventh birthday. It helped that Sunwoo and Jinwoo’s birthday was in May, which was earlier than the month of September when the school year started in Britain. They memorized everything they could find on the Internet that had to do with Harry Potter, and spent the spring vacation of their fifth-grade year bickering over who would get to tear open the invitation when it came.

But because they weren’t living in Britain but in Korea, and in a city full of zealous helicopter moms (although perhaps not as zealous as those of the infamous Eight Schools District in Seoul), their daily lives differed greatly from those of the children in the books. When they came home from school, their grandmother would heat up a snack for them before they started off on their chain of hagwon: math, English, and even essay-writing. Because they were both so-so as students, their parents didn’t try to put them on the admissions track for competitive middle schools. But their parents were still swept up in the frantic mantras that pervaded their neighborhood—”Elementary School Grades Decide What College Your Child Is Accepted To!” or “Elementary Students Should Know the Pythagorean Theorem Like the Times Table!”—and Sunwoo and Jinwoo consequently became more familiar with the insides of their hagwon than with their own home. All the while biding their time until their birthday.

The Harry Potter series gathered dust alongside the self-help books for kids that their parents had bought them, books with titles like: A Twelve Year-Old Takes Charge of Life, I Can Get Into Exclusive High Schools!, or Conquering Princeton. But their hearts were already set on the school for wizards.

So they weren’t surprised when the young man in a neat suit, who looked like he sold insurance or student workbook subscriptions, came looking for them one day. Their birthday had passed a week earlier. No owl had come, but when they saw a white envelope peeking out of their mailbox, they could barely contain themselves with joy. Except Sunwoo, unlike Jinwoo, had a bad feeling that wouldn’t go away, even in the moment the man sat down at their kitchen table and took out a pamphlet.

*

Pretending to have made a mistake, the man slid the English-language pamphlet of that school to one side. Not forgetting to make sure, of course, that Sunwoo and Jinwoo’s mother had glimpsed the full-color photographs of the castle. He then brought out the Korean-language pamphlet, one that featured slogans like “An optimal English-only learning environment” and “A global learning experience.” The school had localized marketing down pat.

The man adjusted his thin horn-rimmed glasses and blithely cast his bait. “This is a study abroad program connected to Sunwoo and Jinwoo’s English hagwon. Seeing how your children are doing, I daresay they could benefit from a program such as this one.” His words were clear and articulate. Even his bit where he gave the slightly cramped apartment a brief once-over was perfect. Sunwoo and Jinwoo went to their room and pretended to do their homework as they hung on every word that slipped through the cracked-open door.

“Because this program isn’t just for, well, so-called rich kids. You see how it says they aim to provide a global learning experience? The school is in Britain, so it’s true there are a lot of British students. But they try to make a point of providing opportunities for children all over the world. Many students from around the world, regardless of whether they’re from an English-speaking country or not, attend our school under this program. This tradition of helping these disadvantaged but talented students passed down from Ms. Helga herself, who was no less than one of the founders of our school.”

“Ms. Helga” no doubt referred to the founder of the least impressive house among the school’s four. Sunwoo pressed down the tip of her pencil onto her math notebook and suppressed a giggle. Not even J. K. Rowling would’ve imagined such a scholarship track existed. Jinwoo had given up on the pretense of homework and was peering through the crack in the doorway. They heard their mother’s voice.

“I’m sure it’s a good opportunity for Sunwoo and Jinwoo but Britain is such a faraway country… and as for studying with children from other countries, I do wonder if that’s really the best for them…”

Cue the type of feigned indifference their mother rolled out whenever she was halfway convinced. Sunwoo sighed. Mother always thought herself a master at bargains. She knew how to seem receptive before pretending to retreat, a surefire way since time immemorial towards getting a better deal. But the man didn’t seem to be in a rush. Of course he was calm. He wasn’t an insurance or milk subscription salesman, he was a wizard.

“I understand your concern, but even in Britain there aren’t many dormitory schools offering full supervision for years one through seven. We also take considerable care to acclimate our students to global manners and the polite customs of England. This is why we insist on having our students room with housemates throughout their years at our school.”

The man tapped his finger on the pamphlet photo of smiling Asian and white eleven-year-olds. “Your children are in grade five. If they were smart enough for the exclusive middle and high schools, their talent would be obvious by now. And if they’re not going to make it here, anyone can see that they might as well go to England and learn the Queen’s English. You do know that British English and American English are quite different?”

As if he had just remembered something, the man plowed on. “According to a recent study, a child’s synapses around the age of eleven are set to the language that they most often use. This is why our school’s entrance age happens to be eleven. Children who are younger need the care of their parents more than anything else. But once their synapses are set, well… there would be no point in having the children go through an English dormitory life.”

The man smoothly lifted the cup of juice on the table before him and took a sip. “In other words, this is not only the best chance your children have, it is their last. But of course, nothing matters more than the motivation of the individual student and the judgment of their parents. Because no one understands a child better than his mother.”

Their mother seemed to hesitate before calling for Sunwoo and Jinwoo. “Sunwoo, Jinwoo. Could you come out here, please?”

Her voice was unusually pleasant. Jinwoo jumped out of the room, but Sunwoo rose slowly. She already knew. Her mother sounded pleasant when she was happy, but also when she wanted one of them to give something up for the other. In their family’s three-bedroom rental apartment, Sunwoo and Jinwoo shared a room, but it was already agreed upon that once they entered middle school, Jinwoo would have his own room and Sunwoo would have to share with their grandmother. She thought, If the main character of Harry Potter had been a girl, Mom and Dad never would’ve bought us the entire series. Sunwoo dragged her heavy feet and sat down at the table. The man gave her a wink. That’s not going to help either of us, she thought. She bowed her head low.

“So,” said their mother, “I’ve been listening to what this gentleman had to say, and I do think this will be a good opportunity for you. Studying abroad isn’t cheap, but even a household like ours…”—their mother’s eyes quickly scanned them both—”… can afford to send at least one of you. It’s not going to be easy going back and forth between Korea and England. It’ll be pretty difficult, actually. But if you still want to go, I’ll let you go.”

Forget about it. You don’t know what it’s like, mother, but the school is another ten-hour train ride from London into the wilds of Scotland. I don’t want to endure seven years of British food. Sunwoo deliberately steeled herself against the idea. Her grades were slightly higher than Jinwoo’s. Like their grandmother said, they were “not high enough to hurt Jinwoo’s pride but just enough for the runt to eke by.” Before Sunwoo could even open her mouth, Jinwoo shouted, “I’m going!”

“Oh my, I guess that settles it for you, Jinwoo.”

Mother gave Sunwoo a look, one that said, And what about you? Sunwoo fixed her gaze down on the rings of condensation left by the man’s cold juice glass, and slowly said, “I don’t really want to go… I don’t want to say goodbye to my friends, and I don’t want to be away from you and Dad, either.” Don’t want. Of course she wanted it. No matter how much she hated something, how could she hate something more than to lose the opportunity to become a wizard? But Sunwoo forced herself to smile. Just like always. Trying to hypnotize herself into thinking that she probably wasn’t missing much, anyway. Struggling to tell herself, that place was always meant for Jinwoo, anyway.

If anything, it was the man who seemed disconcerted at this turn of events. “But we are more than ready to accept both students…”

“No, I really don’t want to go.” Sunwoo got up. “Mother, I forgot I had an extra class at math hagwon. Can I go?”

“Tsch, it wouldn’t do for a girl to be so careless. Fine, don’t be late.”

Sunwoo’s heart was heavy as she returned to her room and packed up for an extra math class that didn’t exist. The man tried to meet her eye, but Sunwoo refused to even look in his direction. She only concentrated on being glad. Now that she wasn’t going to learn magic, she wouldn’t have to hear things like, Why don’t you let Jinwoo have your happiest memory.

*

Once Jinwoo left, the house was quiet. Mother and grandmother constantly worried over Jinwoo’s health. But Sunwoo wasn’t lonely. For the five years that passed since he left, she practiced magic in her room all by herself. Things like half-heartedly making things levitate or flipping cards without touching them. They said wizards who were minors were not allowed to use magic outside of school, but how were they going to go after someone who had never been their student? All the way here in Korea, no less.

There was another good thing. Two years ago, fooling around alone with magic on the playground, someone had suddenly appeared behind her and become her friend.

This was Sao. A friend she didn’t have to share with Jinwoo.

*

“You too, huh?”

Sunwoo was making two pebbles levitate and bump into each other when a wry voice came over from behind her shoulder. A voice from a somewhat exotic face, with slightly darker skin. Sunwoo realized it almost as soon as she turned around. A mixed-race kid. Southeast Asian? Without invitation, the boy came over and plopped down on the empty swing next to hers. He snatched away her floating pebbles and tossed them in the air, catching them and tossing them up again. “Isn’t it the school year in Britain right now? Were you expelled?”

“No, I never entered. We don’t have the money.”

“How mature of you.”

An eighth grader. He had the same jokey way of talking like the boys in Sunwoo’s middle school, which made her smile. He had his regulation name tag pinned to his uniform jacket. “Sao.” A foreign name, but his surname was… oh, it was Ha. Ha Sao. What a name. Sensing a friend, she began telling him things he didn’t even ask her about. Because his saying, “You too, huh?” meant he was also a wizard or something similar.

“I’m a twin. I didn’t go, just my twin brother. He’s been over there for the past three years.”

“Doesn’t he ever come home? He just stays there?”

“I guess. I know he visits London with his friends sometimes, he posts pictures on Facebook.”

“Wait, did you say you ‘didn’t go’ or ‘couldn’t go’?” Sao frowned. “So you’re also a wizard but they only sent your brother?”

Sunwoo nodded.

Sao was annoyed. “I know this is the first time we’ve met and all, but I think your family has a really shitty sexual discrimination problem.” He threw his head back and laughed.

Sexual discrimination. How different those words felt, coming from a mixed-race boy. Trying to hide her blushing, she turned the tables on him. “And you?”

*

Sao was born to a Vietnamese mother and Korean father. His family used to live in the country but they had sold off their property as soon as his grandparents had passed, and came up to the city. Sao’s father’s business was doing better than expected.

“But hey, that Weasley guy in the Harry Potter books? They’re super poor but they sent like five kids to that school. It’s stupid that you guys can’t do that with just two.”

“Please. They have a big house with a garden, right? And their father is a civil servant at the Ministry of Magic? They’re not ordinary people like us. My dad can lose his job at any moment and we live in fear of our landlord raising the rent. Or if the Weasleys are ordinary, they’re British ordinary.”

Sao was possibly resentful of having to live in Korea. He seemed fine with it at first, but if Sunwoo showed any sign of regret when they talked of the school of magic, he’d get angry for her. It was the first time someone was completely on her side. But it was strange and a bit uncomfortable having someone be angry in her stead. So Sunwoo always tried to finish off with a joke.

“If I’d gone too, you would be super lonely. I mean, do you think there’s another wizard in this neighborhood?”

“Eh. The girl’s got a point.” Sao scratched the back of his head.

Sunwoo smiled. “You mama’s boy. You’re the one who’s staying behind because you didn’t want to leave your mom all alone.”

“Can’t you say I’m the epitome of filial piety instead?”

*

Sao was—there was no way around it—a problem student. Along with his dark skin, his hair was always waxed to the hilt. He told her, his expression alternating between embarrassment and pride, that he was bullied in school when he was younger for being small, and that when he moved out of the provinces he had wanted to transform himself into a completely different person, and so became mean. His eyebrows, which were normally scrunched from his making an intimidating expression, would gently relax when he was with Sunwoo, something that she never failed to think was cute.

“Oh, there’s actually one really good thing. Since Jinwoo left, I get to have my own room. If Jinwoo was in Korea with us, I’d have to share a room with my grandmother and he would get a room to himself.”

“Your own room, huh. Well that’s just dandy, Pollyanna.”

Sao was called a chink in school. Despite his protests that Vietnam was an entirely different country from China, the students still called him a chink. Why is that, he would mutter, was it because they were both Communist? Were the North Koreans chinks, too, and the Cubans as well? What a bunch of idiots. As Sao went on and on, Sunwoo lifted some fallen leaves with magic and piled them on his head. Two years had passed since they had first met, and he was now a head taller than her. Sunwoo was beginning to shy away from playfully hitting Sao on the head. The touch of the leaves stood in for her hand. Sao grinned, and willed the leaves to fall into his outstretched palm.

*

“I hate vacation. No cafeteria food,” Sao complained, leaning over his book. It was August, the middle of summer. Sunwoo and Sao, now sixteen, were both high school students. The sight of a Vietnamese mixed-race kid and a Korean girl studying together in a library was an odd sight for many. Especially when the foreign-looking boy spoke fluent Korean. Sunwoo glanced around her and wrote something down in her notebook.

—You actually like cafeteria food?

Sunwoo and Sao went to different high schools. She had no idea why he would want his cafeteria lunches. Sao gazed at Sunwoo’s question for a while and sighed. He scrawled his answer.

—You know it’s my mom who’s the wizard, not Dad. Maybe living in a dormitory for seven years eating nothing but British food takes away your sense of taste. Even the worst cafeteria food tastes better than my mom’s cooking.

Sunwoo tried not to laugh. Sao’s gaze moved to the top of Sunwoo’s head.

—Is British food really that bad?

Sao filled in the blank space underneath Sunwoo’s neat handwriting.

—They boil shit. They just boil everything. They boil it forever. The end. All the Vietnamese food my mom makes is like that so I thought it was a Vietnamese thing. Wrong! It’s a British thing. The Vietnamese food you get in restaurants is delicious.

“I’m hungry,” mumbled Sunwoo, having read over the notebook page full of food talk. Sao twisted his lips and scribbled another line on the page.

—Wanna get some Vietnamese? I know a good place.

Sunwoo shook her head and wrote her answer.

—If my family knew I was having dinner with you, they’d freak out. I mean…

She stopped writing. Her mother had said to her, “It’s bad enough the neighbors talk about you going around with some boy, but did it have to be that Vietnamese mutt?” Surely Sao didn’t need to know about all that.

—Sure. Whatever.

Sao wrote this out in a careless scrawl and went back to reading his supplementary textbook. He gave her a friendly kick underneath the table as if to tell her, “You don’t have to say a thing.”

*

Weird. To wizards, we’re all the same muggles. Your father who married your mother who came from Vietnam, my mother and father and grandmother who still believe patriarchy is God’s own truth. But to muggles, me the wizard, you the mixed-race wizard, and your mother the Vietnamese wizard seem totally odd to them. It’s funny how the slightest change in perspective makes everything look different. That’s one thing I regret not having sometimes; if we were at that school, we’d just be students.

*

Two days after this abrupt end to their conversation, the two found themselves riding on the subway to downtown Seoul. Sao had gone on and on about Vietnamese food, promising Sunwoo he knew a good restaurant. Look, if we go downtown, no one would know who we are. I’d just be another foreign tourist in Myeongdong, right? They love me there more than they love Koreans, right? Sunwoo gave in to Sao’s nagging. The Vietnamese food Sao bought her was ordinary pho and fried rice, the kind they already had in their own neighborhood, but they ate through it while chattering excitedly, and later went walking around in the city crowds. Even when Sao ran straight for the bathroom after taking a curious bite of the cilantro that the waiter, probably thinking Sao was a Vietnamese tourist, had given him a heapful of, Sunwoo felt it was all part of the great day she was having. When a fuming Sao came back after having rinsed out his mouth, she couldn’t help but burst into laughter.

And just like Sao mentioned, no one looked at them strangely in Myeongdong.

“Sometimes I’d have really bad days at school where the kids go too far. I’d go home, change out of my uniform, and come here. I’d go to Myeongdong Cathedral or the Chinese school. My mom speaks Vietnamese and a bit of Mandarin so I can speak a little of both. I can talk to the Chinese kids here. It’s fun. I feel better. Here I’m not a chink, I’m just Sao.”

“Do you ever feel like you want to live in Vietnam?”

Sao shook his head. “They’ll just call me a Korean mutt, probably. I’ve never thought about it. That’s my mom’s country, not mine.”

“I guess you’re mixed-race through and through.”

Sao poked Sunwoo’s side with his elbow. “Yeah, no kidding. I’m a mudblood when it comes to the wizarding world, too. It’s my destiny. Bow down, good sir, bow down.”

The sun began to set. Sunwoo began thinking they ought to be heading back, but she hesitated. She wanted to wrap herself in the anonymity of those crowded streets for just a bit longer.

Then Sao said, “I don’t feel like going home yet. We don’t come downtown every day.”

“It’s just half an hour by subway, it’s not another country or anything.”

Sao pouted. “You want to go home?”

“No.”

The two looked at a map and picked out places they might go. They ended up at the base of the N-Tower at Namsan Mountain Park, but made a face when they saw how expensive the entrance fee was. Instead, they each got an ice cream and started walking around the park.

“It’s so humid,” said Sunwoo. “So humid it makes you wonder if there’s a spell for getting rid of humidity.”

“My mom says Vietnam is much more hot and humid. She loves this kind of weather, she calls it ‘mild.'”

“Well that’s just dandy, Pollyanna.” Sunwoo found herself repeating Sao before she had realized it. “I like the idea of tropical downpours because at least things cool down. But props to your mom for enjoying that kind of weather.”

“Oh. About that.” Sao took another bite of his ice cream. “My mom hates rain.”

*

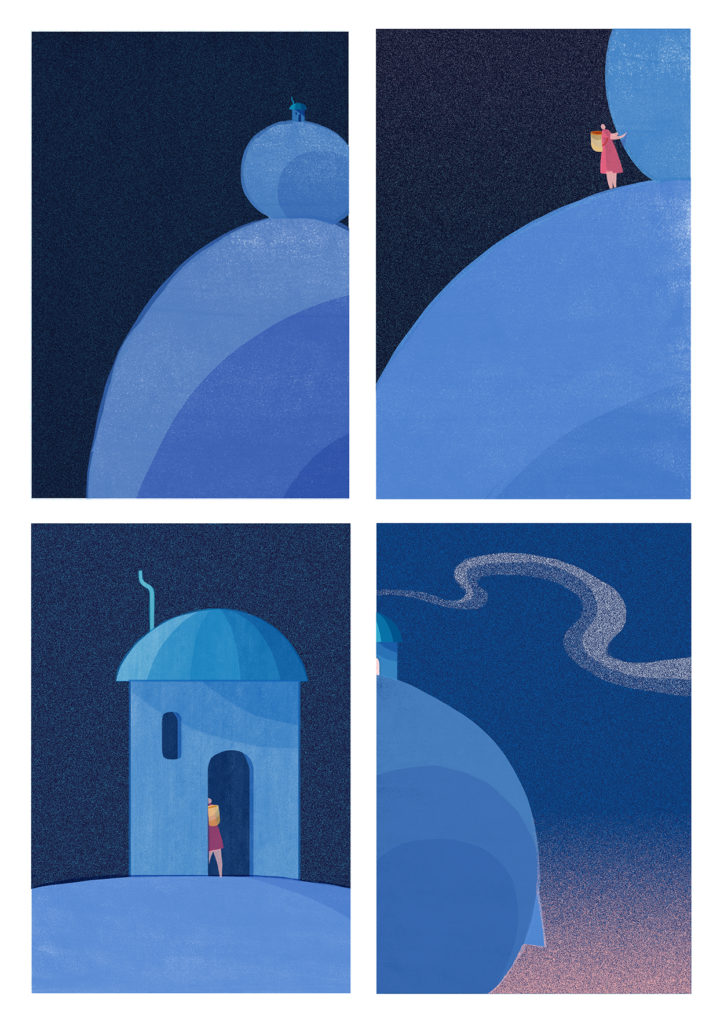

The two watched the streetlamps in the distance start coming on. They slowed their steps. The path down the mountain was getting steeper.

“When the lights start coming on like that,” said Sunwoo, “it always makes me wish for something.”

Sao looked down at Sunwoo and met her gaze. Because of the sudden appearance of his face in the dimming light, Sunwoo’s pupils dilated wide.

Sao narrowed his eyes. “Wish for what?”

“That I want to bash your face in. Seriously. Go away.”

Sunwoo giggled as she took a step back, and Sao snickered with her.

“Kidding,” said Sunwoo. Her voice settled down a bit. “OK. What I wish is… I wish I got to learn this one particular spell.” Maybe as compensation for giving up wizarding school.

“Ah.” Sao nodded. “Me too. But it’s not when the streetlamps come on. It’s some other time.”

“Like when?”

Sao grinned shyly, which didn’t seem to fit with his imposing frame.

“When my mom has nightmares.”

Being a wizard, his mother could’ve worked for the Ministry of Magic after graduation, but she decided to return to Vietnam instead. A month before graduating, Vietnam was hit by a heavy tropical storm, and Sao’s mother’s family was lost in the resulting flood. Lamenting that not even magic could bring back the ones she loved, Sao’s mother decided to return to the country where at least she had memories of her family.

“On days when it rains, my mom looks like she’s about to cry and laugh at the same time. I guess it makes her think of Vietnam and her house and family that were lost in the flood. She gets nightmares on days like that.”

Sunwoo took another bite of her ice cream and nodded. So this was why Sao was so eager to rush home on days when it rained.

She said, “You know that moment right before the streetlamps switch on. That’s the darkest moment of the day. My mom and my grandma both took Jinwoo’s side. And Dad was so busy I never thought of him as being there for me. So when everything goes dark and I’m facing a long night ahead before the sun comes up, I just wish that something, whatever it may be, would keep me safe.”

A vulnerability for a vulnerability. Sunwoo had never spoken of this to anyone before. Sao placed his hand on the top of Sunwoo’s head.

“Don’t be sad. We’re doing fine without magic. Both of us.”

“I know. But still.” We’ll never get to learn magic properly, anyway. Waving a wand and casting spells is so difficult that it takes seven whole years to learn. But if we were allowed to learn one spell, just one little spell… if only they granted us that one consolation.

The fact that they never will only makes me yearn for it more.

Sao broke the silence. “I wonder if the spell you want to learn is the same as the one I want to learn.”

Sunwoo answered, “Probably.”

Not the one that makes people laugh, not the one that disarms weapons, and none of the ones that do harm. But the one that doesn’t hurt anyone else. The one that protects me.

“Expecto patronum.”

As soon as they said it at the same time, the streetlamp right above them lit up.

“Eh?”

“Wow!”

Forgetting about their dripping ice cream, the two stared at the lit-up streetlamp. Even though bugs immediately swarmed around it and the ice cream was making their hands sticky, they couldn’t help but burst out laughing, a laugh like a switched-on light bulb.

“I didn’t know that was the spell for turning on the lights!”

“Damn, I mean, my patronus is a streetlamp? Does it fly around and everything? Wow. That’s so funny.”

The two kept laughing until all the other streetlamps around them had lit up.

Sao held out his hand. “Let’s go. It’s light now.”

“OK.”

“We’ve gotta get home.”

“We should. But not so fast.”

And as if she did so every day, Sunwoo took Sao’s hand.

She thought, this just might be a place where magic happened.

*

“Does your mother use magic?” asked Sunwoo as they slowly made their way down the mountain.

“Only when Dad’s not around. I mean, Dad doesn’t know Mom’s a wizard.”

“What’s your mom’s patronus?”

Sao grinned. “It’s funny. A white dolphin.”

“A white dolphin?”

“I mean, it’s a spectral thing, so it’s going to look white whatever it is. But it’s a ‘white dolphin.’ She says so.”

“Are there lots of white dolphins in Vietnam?” But it wasn’t a matter of calling forth an animal you were familiar with, Sunwoo tried to recall. It had been so long since she’d read any Harry Potter. She’d stuffed the books deep into a drawer and never opened it. She didn’t want to envy the kids who were going to that school.

Sao grinned again. “That’s the funny part. I think they live in the Arctic.”

“But I thought your mom was Vietnamese?”

“Right? Forget about the North Pole, the lady has never been to Northern Vietnam, so why the Hell would her patronus be…”

*

“There’s something I have in common with my mom. She never says so out loud, but I think she finds life hard in Korea, too. But she can’t go back to Vietnam. She has no family there, and she’s tied down by her teenage son.

“I told you why I couldn’t go to that school. You made fun of me for being a mama’s boy.

“Well, maybe I am a mama’s boy.

“I wanted to stand it. If I’d gone to that school, I would’ve become an ordinary student, just like you said. Nobody would’ve looked at me like I was a freak, nobody would’ve made fun of my skin color. But back then when I made the decision, leaving felt like running away and ditching my mom.

“Whenever I came home from a fight, I saw the guilt in her eyes. But I would rather she felt guilty than me just ditching her here.

“I know my mom knows her white dolphin isn’t like a real white dolphin. She’s never seen a white dolphin in her life. But since my mom believes it is… that’s what it is. A white dolphin. Because if you don’t believe it, you’ll never be able to use the magic.”

*

“I wonder what my patronus is,” said Sunwoo when they had almost reached the foot of Namsan Mountain.

Sao pretended to think deeply on it, rubbing the back of his neck and chin. “A dog?”

“What?”

“When I put out my hand back there, you put your paw in it. Just like a doggie. I wonder if your patronus is like, a really brave and valiant dog.”

“How dare you treat a high school girl this way? Do you want to end up as a skeleton buried in Namsan Mountain, Ha Sao?”

“Hey, never speak my full name. It’s embarrassing.”

Even as they playfully batted at each other, the two never let go of their hands as they mixed back into the crowds. To the place where no one looked at Sao strangely and no one nagged at Sunwoo about her life.

*

I wish it were a white dolphin.

A white dolphin is probably a weirdo among dolphins. A hermit of the Arctic, white all over.

But they’re pretty. Seriously, a white dolphin! Swimming alone in the cold, cold sea. Enduring the freezing winters as they come.

*

In the crowds, Sunwoo gave Sao’s hand a squeeze. Sao looked down at Sunwoo. Sunwoo extended Sao’s index finger and gripped it.

“Expecto patronum,” they muttered at the same time.

Let’s wait. Maybe a white dolphin will appear. Sunwoo, looking straight ahead, feeling the flow of the people around them, asked Sao a question. “What memory were you using just now?”

“You know, that thing that just happened. The streetlamp coming on.”

“Aha.” Sunwoo nodded.

“And that idiot grin you had when you were looking up at it,” Sao added.

Sunwoo’s face went red. “Hey!” she shouted, holding up a threatening hand. Sao, grinning, obligingly offered his shoulder. As she repeatedly slapped Sao’s shoulder, she kept murmuring to herself. Actually, I used the same memory. But the smiling face I saw wasn’t mine. It was yours, Sao. Which means we can both use this memory. The thought made Sunwoo stop hitting him. It was true. Sunwoo would remember Sao underneath the streetlamp, and Sao, Sunwoo.

In other words, we’re waiting for the appearance of two white dolphins.

They stopped in their tracks, grinning at each other. They turned to stare ahead. Above the waves of people before them was a huge white cloud rising to cover the twilight sky. It so resembled a beautiful white dolphin leaping over the Arctic surf that the two reached for each other’s hands at the same time.

Jeon Sam-hye was born and raised in Korea. She studied fiction writing in college. Lately she has been preoccupied with the stories of “those who were clearly there, in that moment.” She has published two books, the novel International Date Line (Munhakdongnae, 2011) and the short-story collection Boy Girl Revolution (Munhakdongnae, 2015). She has also contributed to numerous literary anthologies. Her Twitter handle is @co_evolution_.

Anton Hur was born in Stockholm and currently resides in Seoul. His translations of Korean literature have appeared in Words Without Borders, Asymptote Journal, Slice Magazine, and others. He is the recipient of a PEN Translates award from English PEN, a Daesan Foundation literary translation grant, and multiple LTI Korea translation grants. He teaches writing at Ewha University’s Graduate School for Translation and Interpretation.