Black Lives Don’t Matter, Black Bodies Do.

When I was thirteen years old, I wore a white blouse and black skirt to school for the junior high band concert. I went to my home room teacher to ask what time I needed to be in the gym. I wanted to make sure I was checked in to class before I left early. I didn’t want to get into trouble. The teacher, a blonde mid-forties white male watched as I walked toward him. When I went to open my mouth he stopped me and said, “Don’t come any closer. If you were eighteen, look out.” I laughed uncomfortably and kept walking towards him. He said it again with the additional, “I’m serious.” My body stiffened.

Walking to the bus stop in high school I see a car driving down the street. It is a car load of white youth, male, yelling out their window. It took a moment to realize they were yelling at me — the distortion through the wind, “N-I-G-G-E-R-R-R-R!” My body stiffened. My stomach dropped.

I’m at a gay bar in Detroit with a white lover. She’s trying to impress me by taking me to all the hot spots in town. She asks a white gay male where the after-hours spot is. He retorts in the snarky stereotypical accent of his ilk, “There’s a place on the other side of town if you don’t mind too many black people.” He turns and notices that I am with her and simply says, “Oh.” An old rage bubbled up in my body.

Last week I am standing in line at Whole Foods. I am waiting while two transactions are occurring. The white man behind me says, “Are you going to move up?” I turn around and say, “No.” I tell him I am waiting for the two people ahead of me to finish. It’s my turn to purchase my items and the white man follows behind me. He moves my cart to put his items on the counter. I grab my cart and tell him loudly to be patient and wait until I am complete with my transaction. He moves back and tells the woman behind him, “You should move back. It’s safer there.” The new old rage returns and I am reminded of my function — to know my place; to move when a white man tells me to. If I resist, I am the problem. The young white man aiding me with my purchase is stunned. He doesn’t know what to do — he remains silent.

Black lives don’t matter. Black bodies do.

This is a concern informed by our current understanding of intersectionality — the impact of the black body. Skin color, body size and shape, hair texture, how white and straight our teeth are, the color of our eyes, our genders, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, the sound of our voices and class perception within our black bodies impacts the multiplicity of responses we receive living while black. Where we are, who we are with, what we are doing (or not doing) with our black bodies, what words are coming out of our black mouths all have meaning and consequence within settler colonialism.

We do not have lives. We have functions.

The function of my teenage body is to prepare itself for the pleasure of a white male. My young female black body was practice for young white men to learn and occupy their superior place in white culture. My queer black body should not take up too much space; there is a limit to how many black queer bodies can be in one place — lest there will be consequence. My middle-aged black body needed to move in alignment with the speed a white male desired.

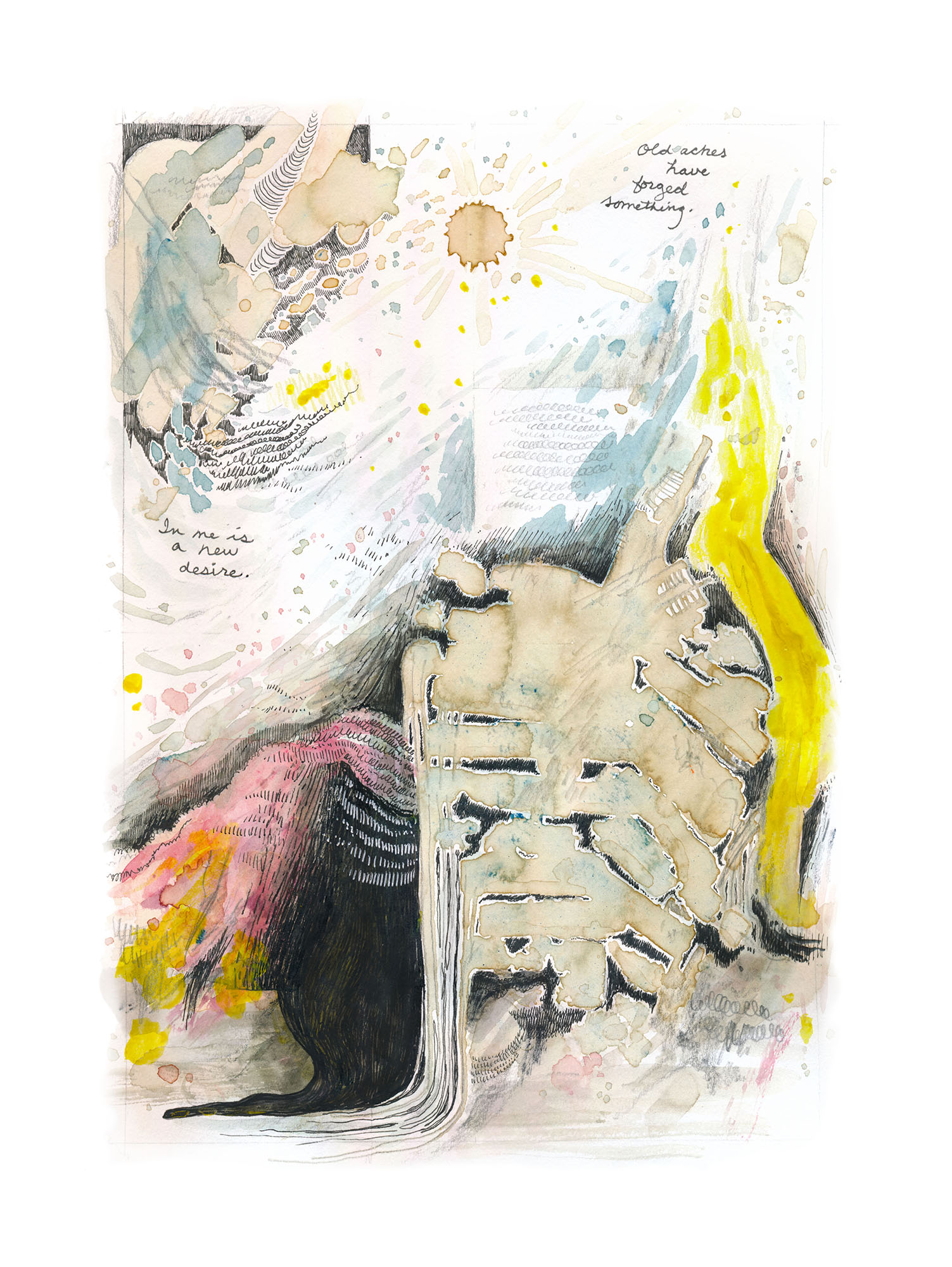

Under settler colonialism, under occupation, “mattering” is of no significance. It does not resonate within empire. How I feel, who I love, what I am dreaming of does not matter. What’s important is how I control my black feelings; my black thoughts and my dangerous black desire in relationship to the function assigned me by white culture.

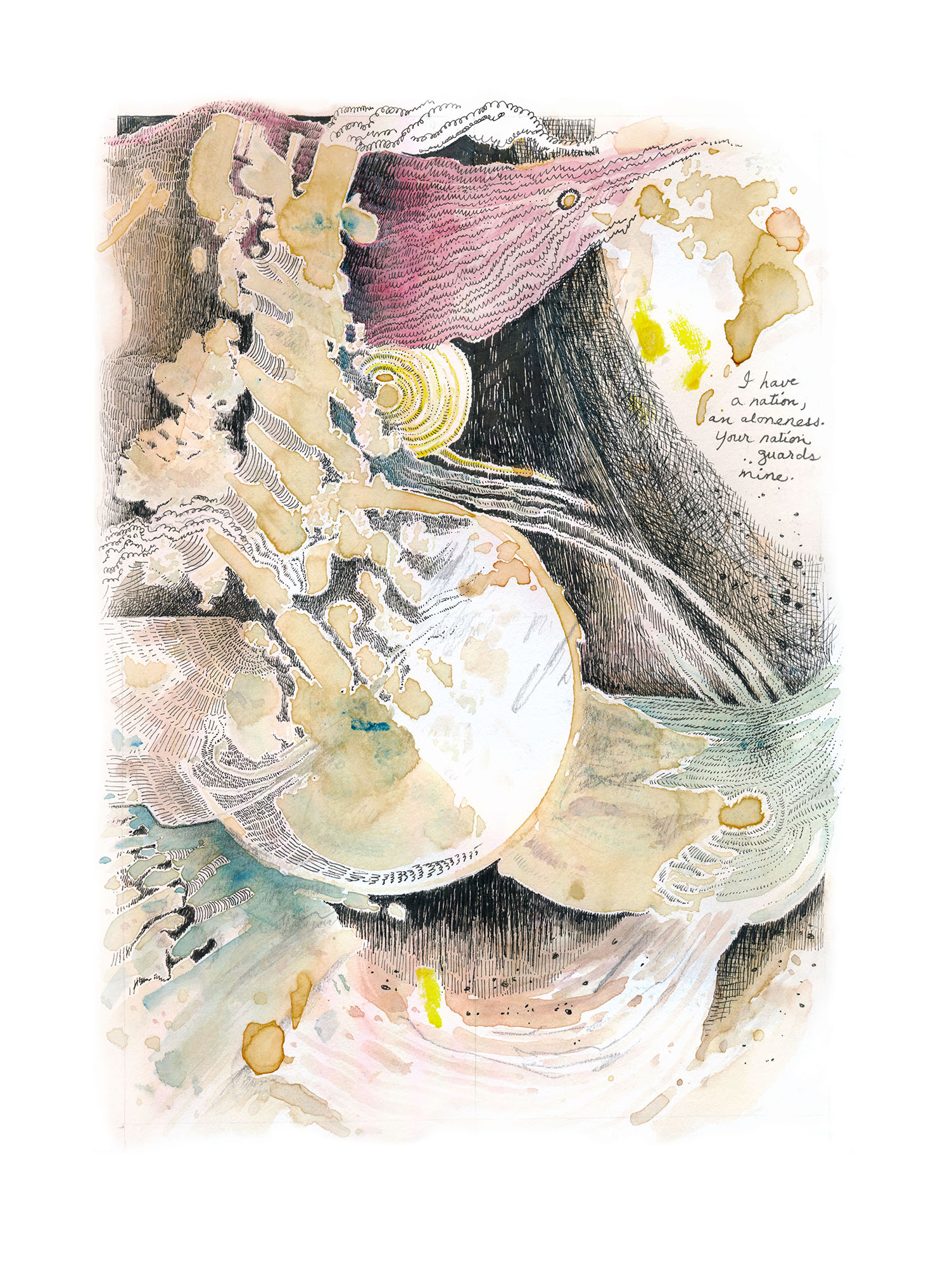

The issue of the sovereignty of black bodies is paramount. Currently we have the right to exist under particular circumstances. The “right” to be in your body. The “right” to breathe. The “right” to have a heart that beats. This does not exist. Black bodies pretend to “be.” In the wisdom of our hip hop elders, “Ain’t no future in your frontin’.”

The right to experiment, to play, to create for oneself and one’s own curiosity has become a right — not what it means to be a human being. We do not have the right to matter.

What we do have are the responsibilities to unravel the old yet very young system that has created these inhuman dynamics. We must understand the stories we tell with our bodies. We must acquire clarity regarding the gaps between who we know ourselves to be and what society sees. We must close this gap by being the foremost authority of our being. Self-mastery. This call is both in service of our sense of self and our membership to our communities (ancestors, family of origin, families of choice, our family across the Diaspora, our extended relations who also face similarly bound perceptions of who they are). Our capacity to be in solidarity is in direct alignment with our willingness to do our own work to be embodied in our truth. That is, the old adage that, “I must change myself before I can change the world” has no meaning if my capacity to know myself has been limited by racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, transphobia, ableism, my undocumented status, my history of violence, etc. It is not enough to understand structural oppression if we do not know the parts we play to perpetuate it.

ANCESTOR 1699. Margaret Copes was presented by the churchwardens of Hungers Parish, Northampton County, Virginia, on 29 December 1699 for having a “Maletto Barstard child”

Only a white male can choose to make a mulatto bastard child. The above is one of the oldest ancestors I can trace. I only found her due to the control of her body which was documented by a court of law.

DISTANT RELATIVE 2016. Jasmine “Abdullah” Richards, a Pasadena Black Lives Matter leader, was sentenced to ninety days in jail and three years probation for “attempted lynching.”

Jasmine interrupted a woman being arrested by the police. Jasmine perceived harm being done to this woman. Jasmine is a queer black woman with masculinity; some call this “masculine of center.” At the center are white heterosexual men (presumably Christian). Located on the margins of white culture, Jasmine’s black body should be used for a different purpose. Jasmine used their body to obstruct and interrupt oppression. By expressing who she actually is and following her conscience, Jasmine was punished and taunted with the charge of “attempted lynching.” The event of lynching which historically and overwhelmingly has been imposed on her kin.

Black bodies have a function under US settler colonialism — the use and abuse of our bodies. We can be worked to death, trafficked, bred, used for sport, mutilated, taunted, tokenized, marginalized, heckled, locked away and murdered. Sonia Sotomayor wrote a powerful dissent in 2016 of a Supreme Court decision that now allows evidence collected from an unlawful stop by police to be used lawfully. Her words speak to the past, present and potential future for the sovereignty of Indigenous, Black and brown bodies if we continue to choose not to engage in a particular kind of liberatory work. “Your body is subject to invasion while courts excuse the violation of your rights. It implies that you are not a citizen of a democracy but the subject of a carceral state, just waiting to be catalogued.” Your black body has been invaded down to its marrow; across space and time. We must birth ourselves — again.

BLOOD COUSINS June 12, 2016 2:02AM. 49 people are murdered in a gay bar on its Latin Night. All queer Latinx and Black.

These brown queer bodies were celebrating, acknowledging, seeing, loving each other; embracing who they are in the face of uncertain outcomes under occupation. They were doing what they were not supposed to be doing — engaging in acts of body sovereignty.

They were punished by Omar Mateen. In this culture, he is a man of color labeled “white” as a person with Middle Eastern ancestry. Like George Zimmerman, a Latino, functioning as proxy for the white heterosexist and racist patriarchy.

Enslavement controlled how we were able to use our black bodies and for whom. Jim Crow controlled where black bodies could eat, drink, live, learn and shop. These words are gone; the dynamics within slavery and Jim Crow still exist (e.g. homophobia, transphobia, police brutality, imprisonment, sexual violence, fat shaming, human trafficking, sports trading). The control of the agency of the black body still exists, is crucial to keeping this project of America turning. Miscegenation laws controlled who black bodies could make love to — some of these laws still exist on the books across various states.

Muhammad Ali’s body paid the price for rejecting the systems perception and attempt to control his black body. There is a cost.

Body sovereignty is the absence of so-called respectability politics — if I control my body in certain ways, I will be accepted. Body sovereignty is the absence of ingesting the system’s archetypal responses to our black bodies — a rejection of the need to matter. I AM. WE ARE.

The desire to matter versus a claiming of our sovereignty is a form of collusion; an asking of the system to acknowledge our function(s) here — this is not liberation. Body sovereignty is the new black. It is blackness without the historical on-going entanglement with white supremacy as a means to understand the self.

If we are constantly engaged in resisting how our black bodies are tampered with, the ability to discover the need to assert anything about ourselves becomes a difficult task. Asserting the sovereignty of our bodies is a gift for ourselves and the worlds we traverse. It is an investment in the future possibilities for our kin to live in the world free of a need to matter and embodying the understanding that their work while alive is to become.

The time is now to claim our body sovereignty; to listen to the knowledge within our bodies. The answers to our dilemmas live there. Oppression deliberately distracts us from accessing this critical information.

The space(s) we occupy daily are stolen. They do not belong to us; sovereign only to the Indigenous people of these lands. Our bodies are our only place of ownership, the work of decolonization — here and now.

— M. Carmen Lane

Revised 6/2/2020

M. Carmen Lane (Tuscarora, Mohawk, African-American) is a two:spirit artist and writer living in Cleveland, Ohio. Their poetry has been published in the Yellow Medicine Review, River Blood & Corn and Red Ink Magazine. Carmen contributed to the Lambda Literary nominated anthology Sovereign Erotics: A Collection of Two-Spirit Literatures. Their first collection of poetry is Calling Out After Slaughter (2015). www.mcarmenlane.com IG: @m_crmnlne.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE