SHADOWS IN A FOREST OF LANGUAGE

a zuihitsu

Chest a mortar for the pestle, stippled like marble. Miracles, the statues that appear soft. My name in the earth, my form wet and new. We give ourselves back to ourselves – I place my present atop my past like a salve. The bruising and swelling have waned. At night, I wring callouses from my hands.

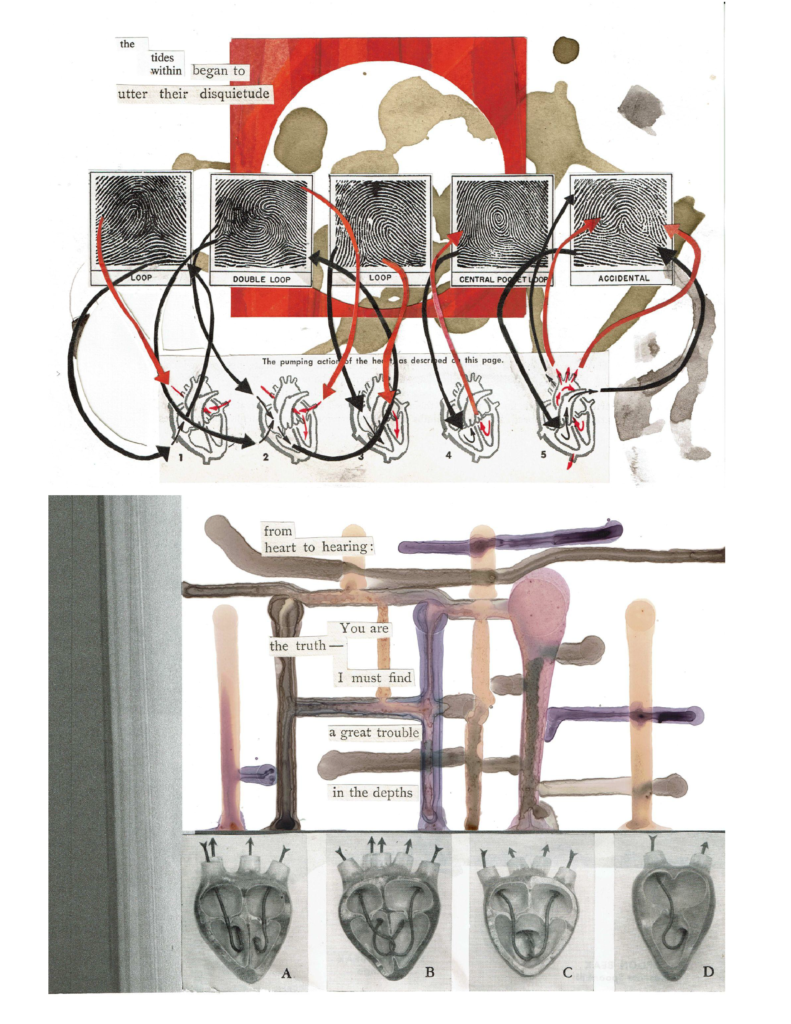

Trans bodybuilder & performance artist, Heather Cassils, Becoming An Image, Performance Still No. 1 & No. 4, National Theatre Studio, London

Binder a shadow I press to my skin with a soft bar of soap in the morning. At night, it is always molting season. I shed and say, “Ta da!” but don’t know which the trick is. I try scratching my back like my mom used to. My hands scamper like animal feet. My nails cross the lines left by the hem of the binder, and we cancel each other out.

The Saint Bernard catches Peter’s shadow between her teeth. It tastes like charcoal and hosiery. The Darling Mother pulls it out and hangs it up to dry on the laundry line outside. Shape of a scoundrel, the Darling Father says, but no one recognizes it. The shadow squirms, thrashes its thin arms, but stays pinned by the shoulders beside other creased outlines of men: dress shirts and overcoats. All the world asleep, silhouettes pressed between wool sheets and heavy bodies, this is the first night his shadow sleeps alone. Worlds away, Peter feels the English wind wander through his body, as if his skin were a silk robe, but he cannot tell the texture or temperature of the hands that reel him in, roll him up, keep him in the bedside drawer.

One winter, every stranger in Ohio takes me for your son. You correct them. The man shaking hands outside the chapel, the little girl in the elevator, the bowling alley owner dressing our soles soft enough for hardwood.

When we played Peter Pan, I was Wendy in the nightgown, down the railing. I buried knowing this. I wanted the myth of my body to stretch ahead and behind me— boy all along. These were the stories I heard others tell: I’d wear my mother’s dresses around the house when she went to Sunday service. / I’d pee standing up, aiming toward tree roots. / I’d walk shirtless, flat-chested, and proud on the beach. But the body has no origin point. Wendy is as much a slip-on as the underslip. When the full-time Peter left, I wore his green slippers everywhere, up and down the stairs that creaked like the buckled backbone of the house. Everyone knew the sound of my footsteps quietly coded daughter, coated green.

I sit my parents down at the kitchen table and tell them my name. Reintroduce the body they lent me. Tall tale in green slippers, ankles pouring out. The silhouette of a ship passes in the window. I read in the newspaper horoscopes on the table that the moon is void of course. Wandering between signs, there is meaning.

Through its drifting etymological history, shadow has referred to “a ghost” (mid 14c.), “a prefiguration” (late 14c.), “an imitation” (1960s), “anything unreal” (early-13c.), “the faintest trace” (1580s).

One night, I take a metal detector to my childhood bedroom. There must be something in the layers of dust, carpet, and floorboard. I set up an infrared camera. There is nothing on the tape but my own body. I pace the room with an EMF meter. The air wavers and shakes like heat, like there is something almost there. I stretch my arms in front of me, a gradient of skin touched and untouched by the moon.

From Michel Foucault’s essay, utopian body: “Utopia is a place outside all places, but it is a place where I will have a body without a body, a body that will be beautiful, limpid, transparent, luminous, speedy, colossal in its power, infinite in its duration. Untethered, invisible, protected—always transfigured.”

Mom texts me the names of the flowers in her garden: Coreopsis (grafted from her mother’s garden after she moved from her childhood home), hosta, iris, lamb’s ear (my favorite), heather (grafted from my father’s mother’s garden), sedum, sometimes portulaca (another from my mother’s mother), butterfly weed, blueberries, and chrysanthemums.

“But there are so many ways to be a woman,” my mother says.

Mint leaves split the zipper of my mother’s black purse. This is what our breath smells like after every meal, state lines and bridges between. At the same time, our mouths go clean.

Socrates in Cratylus considers, without taking a position, the possibility whether names are “conventional” or “natural,” that is, whether language is a system of arbitrary signs or whether words have an intrinsic relation to the things they signify.

The window is shut. Mom sits in the yellow bedroom. My body a stranger. My name a shadow on the underside of her tongue. Peter.

What does it mean to mourn those who are not gone? What does it mean to mourn that which never was?

“Peter Pan syndrome” is the psychological theory that DFAB gender non-conforming and transmasculine individuals desire a flat chest in order to deny the death of childhood.

In Second Skins: The Body Narrative of Transsexuality, Prosser writes that in 1980, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuscript of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) categorized “transsexualism” as Gender Identity Disorder, forcing trans people to “author a history of transgendered identification” in order to receive the proper diagnosis from a clinician to be approved for hormone therapy or surgery. “The diagnosis acts as a narrative filter, enabling some [trans people] to live out their story and thwarting others.” The doctor sentences you to life inside this body. The vessel ages, the shadow plays atop the asphalt, but you do not become.

Derived from Latin to mean “across, over, and beyond,” trans indicates motion. According to Susan Stryker, this means movement “across a socially-imposed boundary away from an unchosen starting place,” not necessarily toward a firm destination. It is the propulsion of the self towards a future we can only imagine.

From Foucault’s utopian body: “From that place, [the body,] as soon as my eyes are open, I can no longer escape. Not that I am nailed down by it, since after all I can not only move, shift, but I can also move it, shift it, change its place. The only thing is I cannot move without it. I cannot leave it there where it is, so that I, myself, may go elsewhere. I can go to the other end of the world; I can hide in the morning under the covers, make myself as small as possible. I can even let myself melt under the sun at the beach— it will always be there. Where I am. It is here, irreparably: it is never elsewhere. My body, it’s the opposite of a utopia: that which is never under different skies. It is the absolute place, the little fragment of space where I am, literally, embodied. My body, pitiless place. And what if by chance I lived with it, in a kind of worn familiarity, as with a shadow?”

Some transmasculine people resist being called a man. Boy is lighter, carefree, brimming with youth and charm. “Is this to avoid complicity with patriarchy and misogyny?” someone asks on a forum called empty closets. Yet boys can be just as complicit. Some transmasculine people recoil at being called a boy, not wanting to be infantilized, kept from growing up. Sometimes starting t feels like a beginning. Sometimes it feels like finally being able to keep living.

Shadow from the Old English sceadwian: “a screen or shield from attack.”

“This won’t heal you,” my mom says as my ribcage contracts.

My friend tells me of a “regendering” website. You send in your childhood pictures, tell them about yourself, and, after some digital manipulation, “receive a visual representation of how you felt inside the day that photo was taken.” Ta da! Like an aura reading, photographing the swell of captive energy. “This is not a science,” they say on the homepage.

On a long walk in Montana, Lena and I talk about starting t— I’m a month in and I’m worried about becoming unrecognizable to myself again— and they say testosterone only unlocks a future that is already inside you, a blueprint embedded down to the cells, the molecules. Months later, we see each other for the first time since then, we’re on a walk in California, and they say my voice is deeper, but still distinctly mine. We both think my face has changed, but can’t describe the difference. The future catches sunlight on my face.

From Foucault’s utopian body: “But to tell the truth… [my body], too, possesses some placeless places more profound, more obstinate even than the soul, than the tomb, than the enchantment of magicians. It has caves and its attics, it has its obscure abodes, its luminous beaches.”

I’m in New York again and today the doctor took measuring tape to my chest to map out how to make it flat, as flat as I’ve bound it for years, flatter even, how to make it look like it’s always been that way.

From André Bazin’s The Ontology of the Photographic Image: “The image of things is likewise the image of their duration, change mummified as it were… [Photography] produces an image that is a reality of nature, namely, a hallucination that is also a fact.”

Every day, the front page of my chest peels, and I press it flat into a notebook.

In 1904, a woman played the first Peter Pan. The director suggested a woman for the part largely due to child labor laws in England stating that minors under the age of fourteen couldn’t work after 9 p.m. The forever boy could not be a man, so a woman instead. It is called a breeches role when an actress appears in “male clothing.” In opera, when a role is sung by “the opposite sex,” it is called a travesty (from the Italian, travesti, disguised).

Nina Boucicault, 1904 & Veronica Lake, 1951

Peter stopped growing, and what happens when you stop growing? Do you have the same skin cells? Do you keep your baby teeth? I know his hair grows long in the winter. I haven’t seen him in years, but when I see him again, he will be the same as I left him. Sometimes you wish for this in a first love, a friend you no longer recognize, a cousin you used to play magic with, a daughter. Is Peter just the echo of his former self? Before his mother shut the window on him on his way out, left him floating, what was he becoming? When I see him again, he does not recognize me. The light that followed him for years is gone, and he doesn’t remember her name.

In Jewish folklore, demons assume the shape of men, but cast no shadow. No law follows them, no conscience grounds them. To stay disguised, they attach their shadows like tying their shoes. When the Darling children fall asleep in the sky, dropping like shot birds towards the sea, Peter laughs so hard he nearly forgets to cut the joke short. His shadow a kite flying alone in the sky. Tinker Bell, his small glowing soul, sticks out her tongue.

In Jungian psychology, “the shadow” is the unconscious, what is hidden and unknown. The ego does not see itself in the unconscious, as this is where the least desirable aspects tuck themselves away. My shadow a pool reflecting.

In Gender Outlaw: On Men, Woman, and the Rest of Us, Kate Bornstein describes the Third Space, an expanse outside the given dichotomy of male and female, outside the suffocating compartments of the binary where “the choice between two of something is not a choice at all, but rather the opportunity to subscribe to the value system which holds the two presented choices as mutually exclusive systems.” I see myself in and I see myself out from the Third Space. It is not just carving space between male and female. It is a space where male and female do not exist. The Third Space is breathing room. A space between, around, and beyond gender. An ambiguity fought for, dreamed of, journeyed to, arrived at, and lived in. A wildness.

From José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity: “Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality.”

Yet wilderness is a fantasy, as much as Neverland. It is a tool of forgetting. After the mass displacement of Indigenous peoples in the land currently occupied by the U.S., colonizers set fire to houses and food stores, inventing wilderness to feign the idea of “untouched,” Edenic land. The myth of “the New World” and its “virgin land” constructs a vision of emptiness and idleness in order to make room for the myth of the pilgrim. The shadows bend over backward.

In “The Colonial Origins of Conservation,” Stephen Corry writes of the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act in the conservation movement, how it legalized the eviction of Ahwahneechee people from the land— all except those who were forced to serve tourists, adorn racist costume, and perform caricatured dance and rituals that were not their own.

Neverland is a colony. Stepping out of the window in Kensington Gardens, Peter floats on his back like an otter over the city, past the second star to the right, to invent a utopia of perpetual war, eternal childhood, and ever-replaceable dead. According to Barrie, every child sees their own version of Neverland. It is where imaginings come true. “A lagoon with flamingoes flying over it” or “a flamingo with lagoons flying over it.” The lost boys flit over eagerly and form a militia at first light. Clad in skeleton leaves and cobwebs, the lost boys’ bodies are bodies of forgetting, rewilding over their own origins. Neverland, outside of spacetime, blunders on outside the colonial idea of progress. A still image of empire. The first bloody battle, over and over. Violence laid bare, violence of pure entertainment. A clock ticks inside a crocodile. Peter terrorizes, and time turns over again like pulling taffy.

From J. M. Barries’ Peter Pan: “In [Peter’s] absence, things are usually quiet on the island. The fairies take an hour longer in the morning, the beasts attend to their young, the r*dskins feed heavily for six days and nights, and when the pirates and lost boys meet, they merely bite their thumbs at each other. But with the coming of Peter, who hates lethargy, they are under way again: if you put your ear to the ground now, you would hear the whole island seething with life.”

John Locke’s theory of acquisition is the founding liberal law that states if one uses land “productively,” for profit, one is granted private ownership of the place by the grace of God. This theory underlaid the legal ruling for the forced displacement and genocide of millions of Indigenous people. When Peter returns to Neverland, in the absence of war, he sees idleness, lethargy. He makes it his again. The lost boys busy their hands with blood.

Fences jut out from the grass like white teeth. When the Darlings reach Neverland, the lost boys have built a house for Wendy: adornment of roses up the walls, knocker on the door, chimney atop. But flies come in through the windows and doors. Sparrows take apart the thatched roof straw by straw for their own nests. The seasons don’t change, the wind doesn’t let up, and eventually, at the turning point of the house becoming a project, a settlement, Peter abandons his fatherhood. He flees into the heart of Neverland, the safety of the neat binaries of war: good versus evil, self versus other. Meanwhile the rest finish what they started. The lost boys fly off, and on the other side of the second star, they morph and twist into men: lords and judges and office workers. Wendy becomes a mother somewhere else. Peter comes by sometimes to ask her and her daughters to clean the cottage. Neverland errs on without a past, without a future.

From Kyle Powys Whyte’s “White Allies, Let’s Be Honest About Decolonization”: “Allies must realize they are living in the environmental fantasies of their settler ancestors. Settler ancestors wanted today’s world… [F]or many Indigenous peoples in North America, we are already living in what our ancestors would have understood as dystopian or post-apocalyptic times.”

I sat at the top of the staircase and batted those green slippers back and forth. Embodying boyhood for me meant embodying white boyhood. I followed where I thought I saw my body. Was to slip on boy to step further into the lineage of those who strung up the binary in the first place? A transgression or submission?

Colonialism is not a shadow sewn to the feet. It is the pale feet. It is the colony that each day makes and remakes itself. Memoryless. A body intent on forgetting.

I sit and watch Peter somersault through the air and never get dizzy. The ivy sewn across his chest never crisps or browns. He sings high notes from the diaphragm when he wings over rooftops. His feet never fully touch the ground. I’m seven years old and he’s an idea in my back pocket like a faerie, he’s a small light I conceal in my small fist. He’s a whisper that goes: I could be boy, I could be. Poster child of children, there had to be something enviable too in his innocence without innocence, something truly boyish about it. By this I mean his untetheredness, his lack of responsibility or tie to anyone or anything, the fantasy of being a young white boy. But it only takes til the end of the play to realize the tragedy. Peter flies alone over his wilderness, his shadow straying behind in the wind, remembering everything.

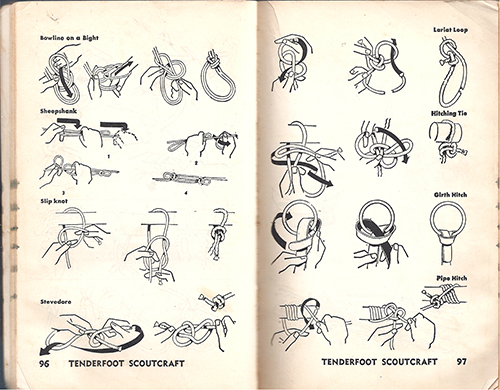

Is the formation of a thought the act of pulling a knot tight or unraveling it? Is the way out both the practice of knotting together and coming undone?

Knots & Hitches from Boy Scouts of America Handbook, The Handbook for Boys (1910)

From Google: Are shadows real? Are shadows made of atoms? Are shadows longer in winter or summer? Do shadows have color? Do shadows have weight?

Unmooring: the act of releasing all ropes and anchors from a vessel. I have dreams where I unmoor everything from its name and I leave my body for the time being. This is a fantasy. There are times I see myself stray toward Neverland. There is fluidity in gender, in my body, but at the same time I am tied to my materiality, the history I am embedded in, and what it demands of me.

Queerness is not white, cannot be assumed white, must not be controlled and regulated by whiteness. Queerness is a devotion, to ourselves, to one another, in friendship and solidarity. Sometimes our eyes slip into each other’s on the street. An eclipse— a glow visible at the edges.

We cast and throw our shadows. They run through a forest of language from which we’ll never find our way out. But we call our shadows in at night and find they are our bodies exactly, lovingly, even stretched, stout, visible or discrete. Yielding and unyielding. We soap and stitch the dark to our feet. When I bind my chest, my silhouette records the difference.

Fox Rinne is a trans poet living on occupied Lenape land. Their writing can be found in Baest, tagvverk, Jacobin, and more.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE