Funeralesque

The mourning was held at a deluxe parlor. The carpet so deep and new that any depression elicited by your step rebounded instantly underfoot. On an elevated dais below a two-story-tall projection of our savior, a clergy-member pronounced us remnants and witnesses. He was a small, discount thundercloud, his waving hands pudging over his tight-buttoned cuffs, his chest puffing and charging him three feet forward, then a leap back. Still, beneath him, faces glistened, overt with feeling. The things he said affected them like a wind tormenting a field of wheat. I’d seen videos of such fields. Never in person as they were not of this world. A man a few seats down from me gripped the back of a chair with both hands to keep upright. He was mouthing along to the minister. His wife next to him, dissolved in grief. I wondered who they were, what complex of relations and events bound them to the deceased.

I spotted Loren, mostly via his hair—he had completely changed it, styled and combed it quiet, so that it offset his posture of sorrowing. His face was different too. So different I hardly recognized him. But his hair was the same color, and as I scrutinized him a lick escaped the orderliness of his facade and touched the exact midpoint between his brows, indicating to me.

Hi, I called, sotto voce, when he passed my row on the way back to the reception area. But the man flicked a puzzled look at me and continued on, not breaking stride, like he didn’t know me.

Maybe I was wrong, and he didn’t.

At the front of the hall a wail went up, shot like a flare. If I looked up into the cloud of emotion above us that had amassed from this last hour of ceremony it would be spreading like a red and diffuse light. Raining flecks of her acid distress on my upturned cheeks. It was always a woman.

The man, Loren or not-Loren, came back. The lick of hair was pressed back into place. He took his place in the front row. He had gotten there before me, so I had placed myself two rows behind. Not wanting to complicate his fiction with the intrusion of my known face. I stared at his back. For a moment, his profile was visible as he looked behind himself. His eyes scanned the congregation. He was searching for someone. Someone he knew who knew the absence at the center of this event, who could draw him deeper into it. But had Loren ever sported a beauty mark just above his right cheekbone? Was he capable of smiling as painfully as that?

The woman was the deceased’s mother. I could’ve guessed. She was speaking. The savior rippled above us, disturbed by a psychic transmission from the netherworld or a frisson in the equipment. The mother’s back was to it, so she wasn’t aware. As she spoke, her whole body sagged, clinging, against the casket. Her voice was composed—it hardly shook—but her body betrayed her.

Ma would’ve hated to go like this. She would’ve squalled and kicked and berated us for even bringing up the idea. She never wanted anything to do with these public displays, the wreaths of plenty overhanging the slender box, the dead housed with all of their belongings. Better to go quietly. Just a few loved ones to tend to you. A plain stone sunk quietly into the pond.

After the mother, a procession of four or five people followed. They each bowed to the casket. Then spoke. But their words pinged off my consciousness like grains of sand. In trying not to think of Ma, I was thinking of her. It was a relief when they finally called me, too.

I worked my way over people’s laps on the way to the aisle. My speech was folded in a sweaty half-page clutched in my hand. I approached the man. He had moved into the seat right next to the aisle. In the moment of passing he looked up at me and I down at him. His expression was stripped by sorrow to its rudiments—slashes of eyes, mouth gripped so closely over its teeth it implied the entire outline of his skull. I knew I’d been wrong.

I mounted the steps. Up close, the apparition of the saint was far more lifelike. She wore necklaces of thorns around her long throat. Her expression was beatific and upward-aimed. She shone white and solid as candle wax. My neck prickled. I neared the casket. For a moment, because of how the others had bowed, had wept, had placed their bodies on that box, I expected to see the deceased’s material figure, his reupholstered and painted face with the lips sewn shut over an unquiet tongue. But the casket was empty like they told me it’d be.

There were many events like these. For people buried in blizzards, or swept away by hurricane winds. The elements were ruthless. But ice storms and winds were actually the merciful encounters. Better to be disappeared than savaged beyond recognition by fire, or have your face cooked underwater to the softness of stewed plums and picked off by fish.

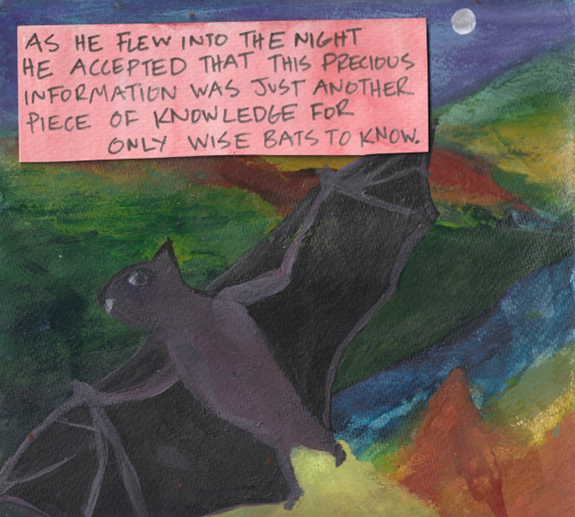

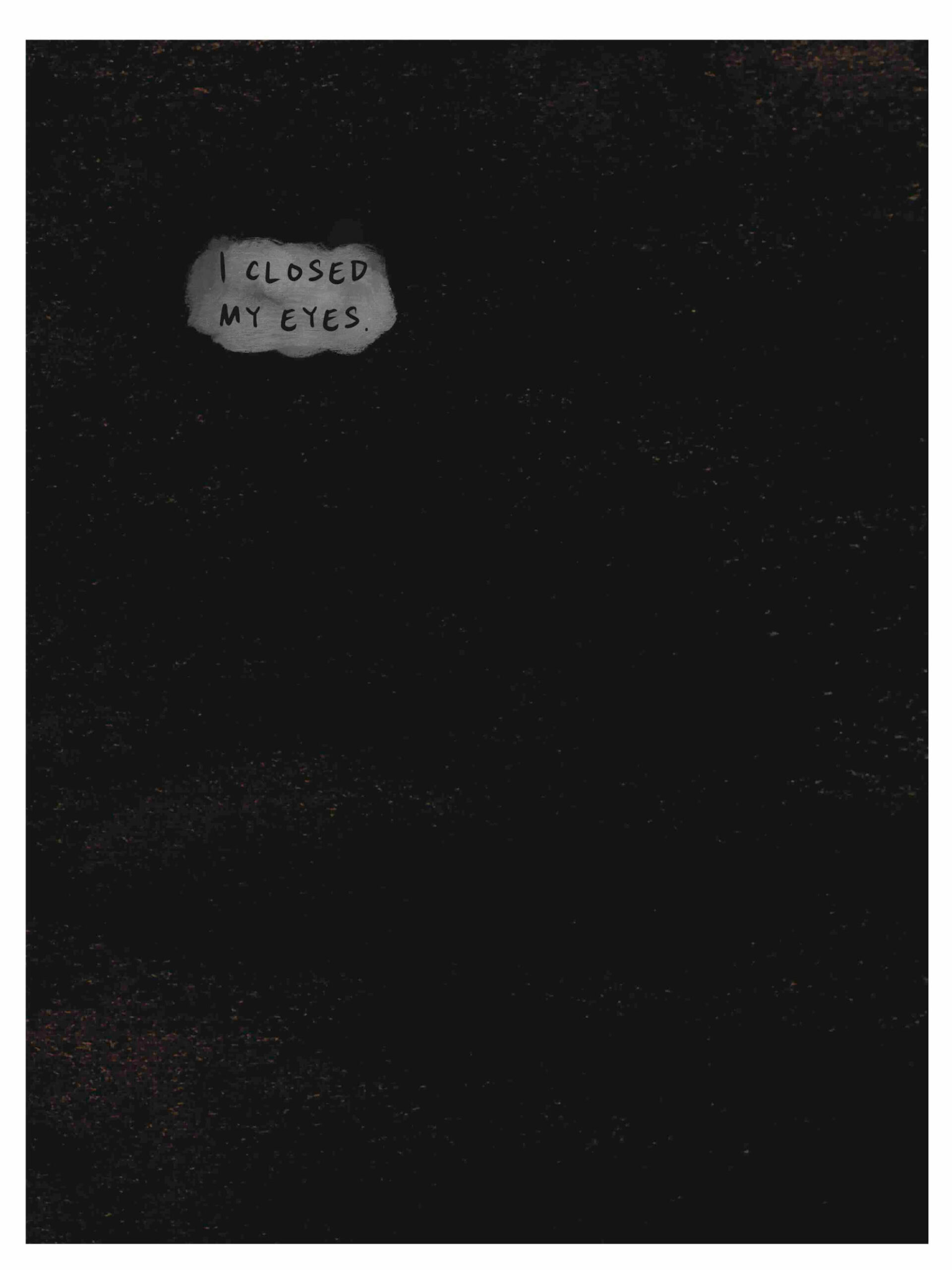

I put my head to the casket’s polished edge. Ma. Are you there? Hearing nothing, I rose and moved to the lectern. The bright lights burned my retinas like suns. My fingers jerky, ungreased, I unfolded my page of notes. I tried not to read from them. Funny how easily in Los Angeles I flew off-script, improvising wildly, never keeping to the exact letter of what the writers wanted me to say. Untethered by reality, I was freed to invent. But that was another person, another place. Today my eyes kept returning to my page. I was trying to describe how important this person had been to me. Her absence a crater miles wide in which nothing would grow. I was trying to impress on everyone out there how important a person, any person, is. How vital, so that when they ended, reality itself underwent a transformation, became thin and membranal, and it felt as if you could pass through walls and other people, clean and transparent as wind. Did you know, a producer of documentaries once told me, that we and everything around us are made up mostly of empty space? Emptiness was necessary to the construction of us and of the world. Long, tense spans between atoms, that swayed invisibly like bridges. But I didn’t know the words. How to say this. I hoped they mistook my confusion for grief, so convincing that I strangled and hiccupped.

*

I blinked and found myself marooned in a crowded, chopstick-clattering restaurant. It took me a moment to recognize the clouded glass windows with their peeling enamel of menus and specials, and the language of the conversation that rose and dipped around me, punctuated by bursts of laughter. Cantonese, the language Ma spoke, which Lee and I had inherited from her only in bits and phrases.

I remembered that prior to my arrival I had been walking aimlessly, looping the blocks, trying to shake off the day. Rehearsal, submergence, and re-emergence made the hours slender as seconds. Before me was a bowl of congee chunky with pieces of thousand-year egg. I must have ordered it. I got up to find a spoon, obediently as if at the direction of my past self.

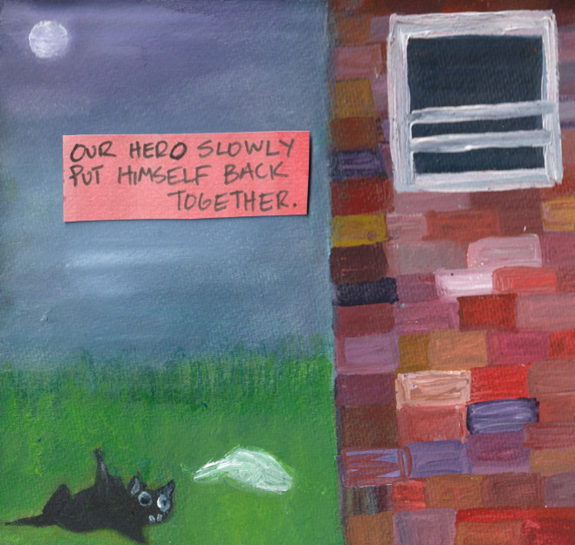

Analisa, in shoulder-brushing gold hoop earrings and black tights that cut off mid-calf, was mopping the floor behind the register, a phone tucked into the crook of her chin and shoulder. Her back was to me. It gave me a jolt. I didn’t want her to see me like this. Confused, intermittent—reconstituting myself. But before I could duck away, she pivoted mid-swab and saw me. The corner of her mouth quirked up and she gave a little wave. I smiled, but the attempt gripped my face in an odd way. I plucked a spoon from the bouquet at the counter and escaped back to my table.

No sooner had I reseated myself than the door opened in a tingle of bells. A band of teenaged boys tumbled in. They looked so young it hurt my eyes. Like boisterous puppy dogs they piled in at the table next to mine. They ordered, in a cascade of interruptions, from a teenaged girl worker wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with a mouthy slogan, who rolled her eyes at their pleas and cracks.

I noticed one of the boys was quiet. He didn’t joke with the girl but made his order politely, his face red as a beefy tomato, and though I could see nothing odd about this his friends all went absolutely silent, a silence loud with repressed and filthy commentary. The girl didn’t look at him, but it seemed her sarcasm softened, and she smiled down at her pad as she jotted his order.

After the girl server left, the boys’ attention veered. Two of them excused themselves for the restroom. One of the boys drummed on his overturned plastic bowl with two plastic spoons while ricocheting rhymes back and forth with his friend. Another three were having a contest with the jarred marinaded slices of chilis peppers that sat table-side, taking turns sucking as many spicy pepper seeds up their nostrils as they could muster. The last boy was sitting in the middle of all this, unspeaking, his face still red but a little less so, and I didn’t understand that it was happiness, pure happiness, that made him quiet, until the lights flickered, off, on, off again, and everyone looked up. For a moment I was afraid it was an outage, one of those abrupt unannounced black-outs that cut air to patients on breathing machines in the hospital and marooned us in a darkness that was outside of society. But then a wavering light was moving towards us in the dark restaurant, and as it approached I saw it was the two boys who had gone restroom-ward, ushering with them the girl worker, who was holding a big sheet cake on a tray, looking a little embarrassed, but also, delighted. The cake was made, I knew, from one of those cheap boxed mixes, but still, it was an impressive cake, topped with frosting and sprinkles and stuck higgledy-piggledy with colorful candles. They, that is, the delivery procession, came to a stop at the table, and the heckling and hooting boys quieted. The red-faced boy looked up at the girl he liked with touching solemnity and his face split into a smile. When he cut the cake, everyone started, badly and in mismatched cacophonous keys, to sing.

In the outages, the worst hit were the hospitals, the morgues, and the ice cream shops. Why did I think this, as I sat in the dark, listening to the celebration at the table right next to mine?

When the lights came back, the boys were eating their slices of cake with unguarded relish. The girl waitress and the red-faced boy were talking, haltingly, in undertones. She was shoving loose strands of hair behind her ears and he was looking at her then back at his hands then back at her again. I envied them their blundering earnestness.

And here was Analisa, approaching, wiping her sweat-shiny forehead with her forearm. The boys perked up under the weary daylight of her smile.

Steven, she said, waving her hands like a magician gathering her birds. You want a picture? I know your ma will. C’mon, sit together, I’ll take one.

She took one photo, then two more, of the girl waitress leaned in grinning, the boys pulling faces. But then they wanted a picture that included her too.

Analisa said, Hold on. And she cocked her head and said, Hey, V., can you help? She held out her phone. The table of boys looked at me for the first time, I think for the first time realizing I was there. For a moment I was confused, too, and uncertain if I was. What was this world that was right beyond the border of mine, rife with laughter, impervious to the deletions and blurrings of death? It seemed impossible that the two could occupy the same plane. In fact, when I took Analisa’s phone—humidly warm from her grip, decorated with small, cute stickers—and rose to position the picture, the photos I took were grainy and blue-hued, the smiles unnaturally bright as if transmitted from another dimension.

*

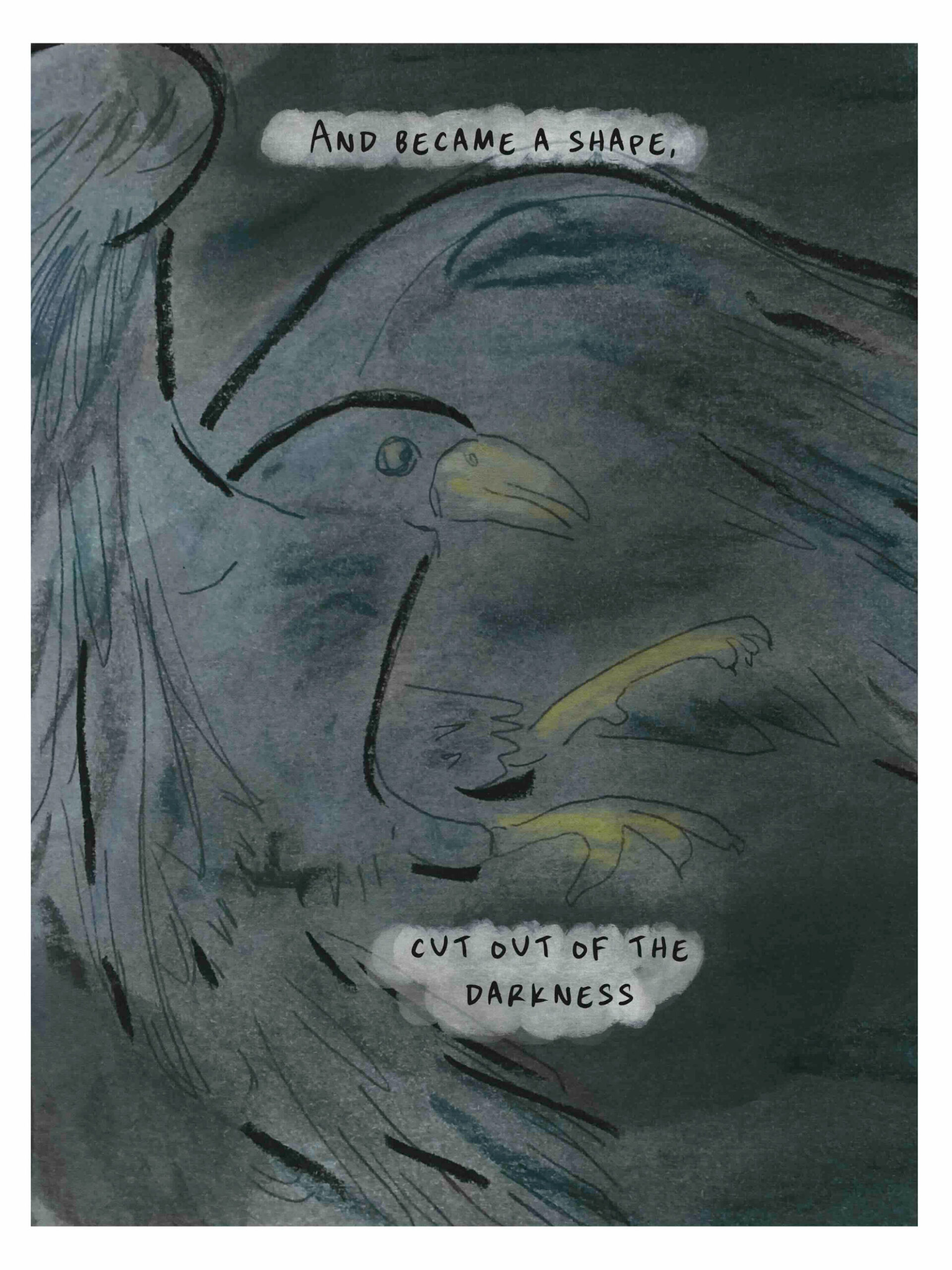

At this one, everyone was strangely chatty, like we had just met each other at a conference hosted at a resort and were trying to make friends. How did you know the deceased? She was my coworker; my god-aunt; my friend; my eclectic, intermittent neighbor who watered the tomatoes with a mineral-rich brew made from her own aged urine. She was descended from Mexican emigres, Hokkien refugees, Scottish traders—a medley-line of itinerants and adventurers and wanderers. She had a face like something cut into stone, but when she embraced you, you felt as soft and comforted as if you could lay your head on her shoulder and drift to sleep. She always laughed at my bad jokes and made me feel like she meant it. She was tough. She was a field biologist. She once broke her arm in a jungle, strapped it in a splint and carried it on her for four days, and on the fifth discovered the last colony of an elusive species of frog, whose skin secreted the answer to the riddle of a particularly ravenous cancer. We always used to joke that in the dystopian, bombed-out future she alone would remain alive, tearing squirrel jerky with her teeth, sewing menstrual pads out of thread and wads of moss. How did she not make it? She was wily, implacable. She wrote a one-hundred-and-sixty-page dissertation living in a yurt in the high desert while high on tranquilizers. She climbed a mountain to take a condensation sample from a shy cloud. She could do anything. She was my wife.

No one said: She was my mother. A small relief. I couldn’t have tolerated meeting another like me. Orphanages were difficult places, mirrors quaking at each other, provoking fists to splinter the sight of one’s own pain multiplying into infinity.

How did you know her? I was asked.

I said: A treatment I received when ill was developed from her long and persistent research into chromosomal antiquities. I am alive because of her.

Wow.

Yes.

Did you ever meet her? When she was alive.

No, I said. But I thought I would come meet her now.

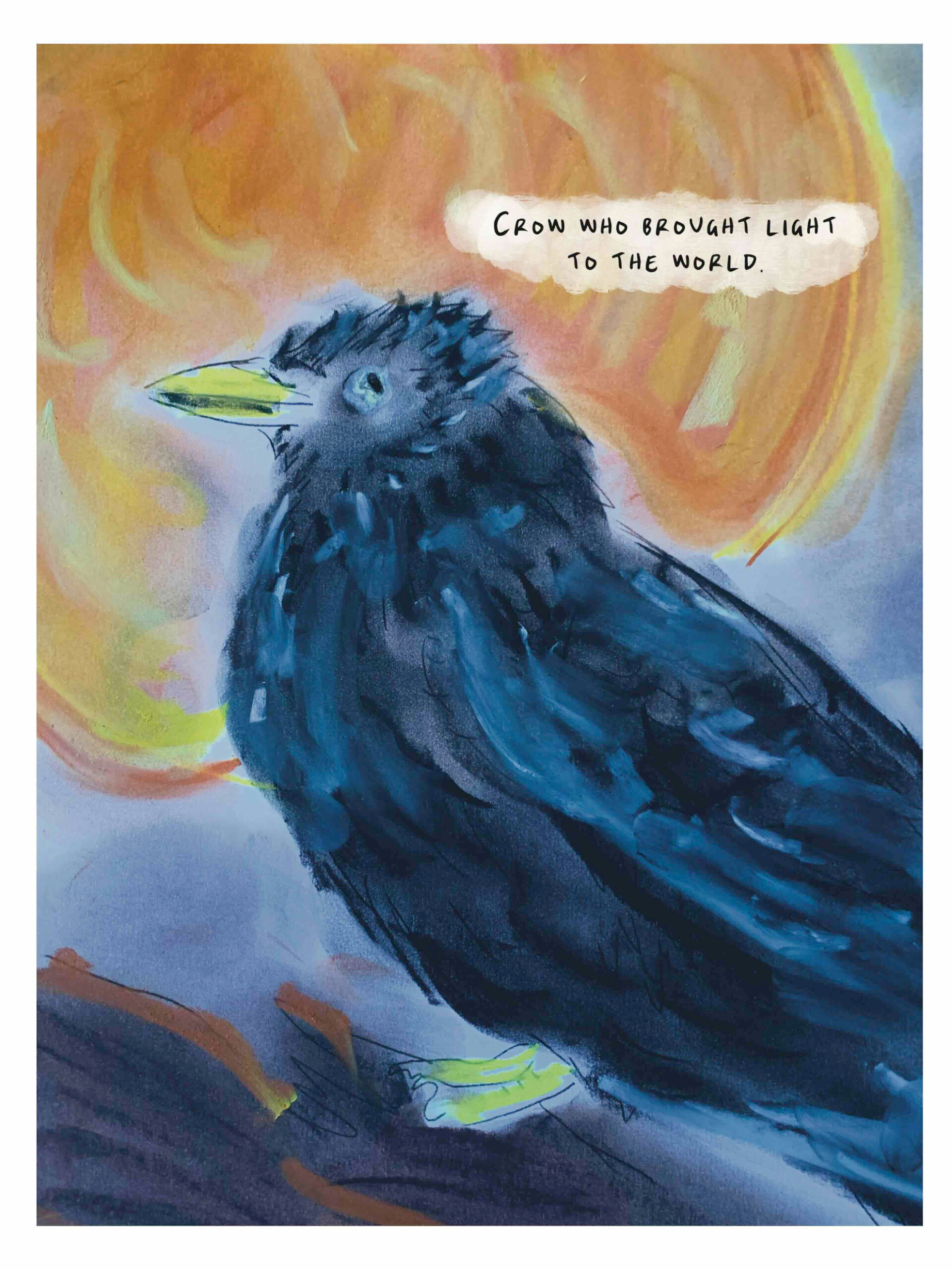

And that was what it was like. The person a composite of anecdotes, of words attempting to conjure her anew. Each person here kept a piece of her. If I spoke to enough of them I could see her. I kept speaking, and listening. And out of the edges of my eyes, she came closer. I saw her flinty stare, her unmovable conviction: However ravaged the world, it remained worthy of being saved.

Who was this woman to me? Someone in whom a thought had begun, gained detail and clarity, surfaced into the world, acted through others, deployed analyses, mechanisms and productions, and, years later, caused the preservation of my life. Didn’t we all owe someone in this way? Every medicine invented and taken, every kindness performed and received, every intervention, every act of care, every life-giving touch, began first as a thought in the mind of another.

I did not say she was my mother. Though I don’t know why, the thought played at the edge of my mind, like a child along a border of wire.

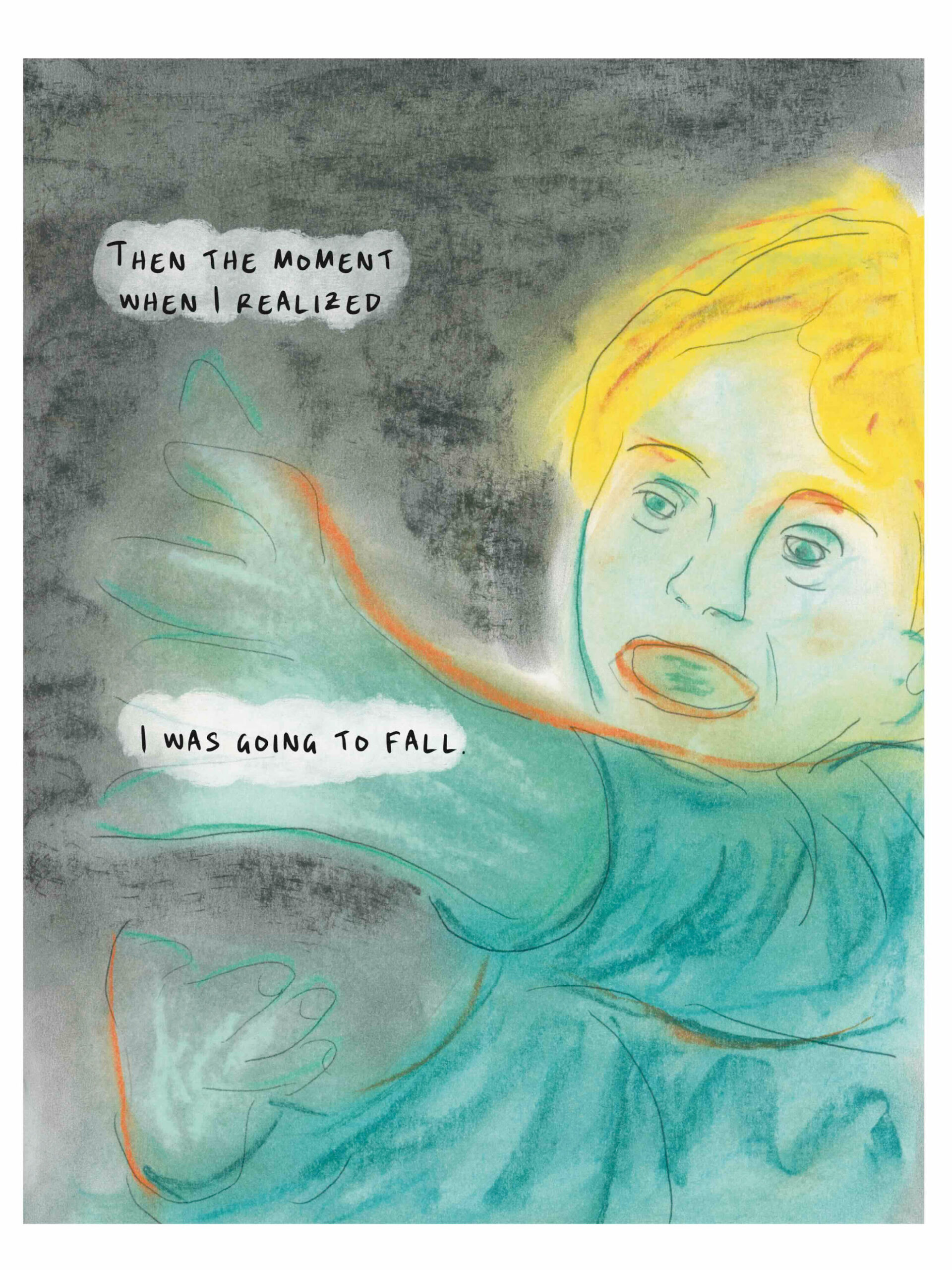

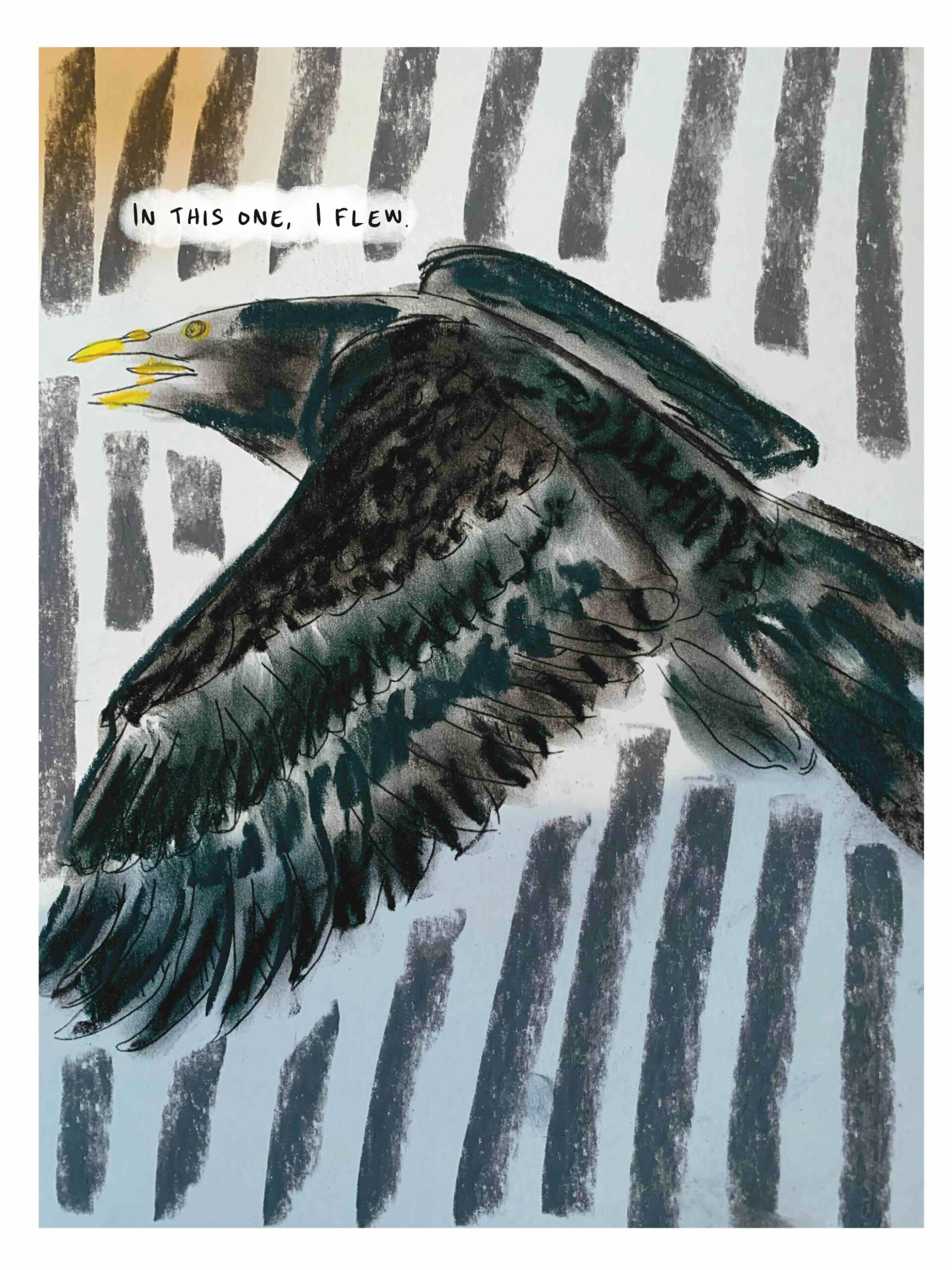

In the middle of the service the wind picked up. At first I thought it was just a squall. It was not the season for anything more. But someone ran for the double doors and shoved a long bar down, barricading it. Another ushered attendees away from the windows, herding them into the aisles, where they stood, crowded together. The speaker stopped speaking. I remained in my seat, right next to the aisle, surrounded by the agitated attendees. In silence, through the same windows which we had been hurriedly conducted away from, we all watched the world outside. A muffled movie. The trees jacked and thrashed. Parked cars rocked on their wheels. A broken-winged umbrella chased itself down the street, followed by a dragging deck chair, which at the last minute lifted and rammed a window-front. The speed increased. Clouds of birds, trashed television monitors, shopping carts, runaway racks of discount clothing whipped through the streets, light as blown foam.

Then a booming impact shook the roof. The people who held the pieces of my mother scattered. They raced for the doorways, where the structure might hold up. I didn’t move from my seat because, at first, I didn’t believe this was happening. I looked up and then away, wiping; tinging grit had drifted down into my eyes, shaken loose by the crash. But no hole appeared in the roof. Whatever had crashed was not intent on entrance.

Nevertheless I rose, and—my self-preservation instincts now so sluggish I could hardly believe I had once run nine miles in a day to outwit a wildfire—moved slowly to the edges of the room.

The walls rattled like panes of glass, then stilled. The wind canyon outside did too. The roof reverted to its solid state again. While a few of the attendees went out to investigate and report any damage to authorities, the rest of us remained standing, uncertain.

Then someone spoke. It was the husband of my mother. Was it not important to persist? he said. The wind had stopped. The roof continued to stand. She would not have wanted us to discontinue the service.

I looked up again. It was true. The roof was still. No grit drifted down to dot my forehead or catch in my lashes.

The husband climbed the stage and faced us. His face was impassive. His voice, shaken at first, had gained a solidity and evenness that calmed me slightly. He said: We will tell stories of her. In this way she may remain alive for another day.

I wondered what had fallen on the roof. A great oak stories tall. Pieces of another building. Perhaps the wind had picked up a car, carried it for miles, then dropped it on top of us as a forgetful child does a toy.

Who would like to speak? the husband said, looking over us, the crowd.

The people who carried the pieces of my mother murmured. A few of them slowly took their seats while others continued standing, looking shocked, or frightened, or confused. Still others gathered their things. It was dangerous, I heard them murmuring, it would be better to leave. We can arrange another commemoration, at a more convenient time. And more and more of them bent to retrieve their purses from the floor, their coats from the seats, and they shook hands and embraced as they headed for the exit, out into the world, where the wind had laid down quietly in the streets after exhausting its great emotion. They took the pieces of my mother they carried with them and they walked out and away.

There were just ten or twelve of us now. I wanted to chase yelling after the ones who’d left, but instead I sat slowly in a chair.

The others began speaking again. Softly, their voices rose. Once she survived three days by herself in the High Sierra in a snowstorm. Once she built me a small shed on the hill behind my house that I could sleep in with my children when the flood swamped the house, bursting out of drainpipes and overflowing the tub. She liked to collect seeds and specimens. She could grow a garden to feed a party from some dried pods. She taught the people she loved how to cut wood and carry water, how to set a splint and read how moss grows, and even more than that, she taught us how to think and how to feel, and how to protect how we thought and felt not only from the wildfires and hurricanes and torrential winds, but from all the savages, depredations and losses of living, so that we could continue on in our small and incremental ways. What did she teach you? Who was she to you? What did you learn from this person who was so important to us?

They were looking at me. I was the last one to not have spoken.

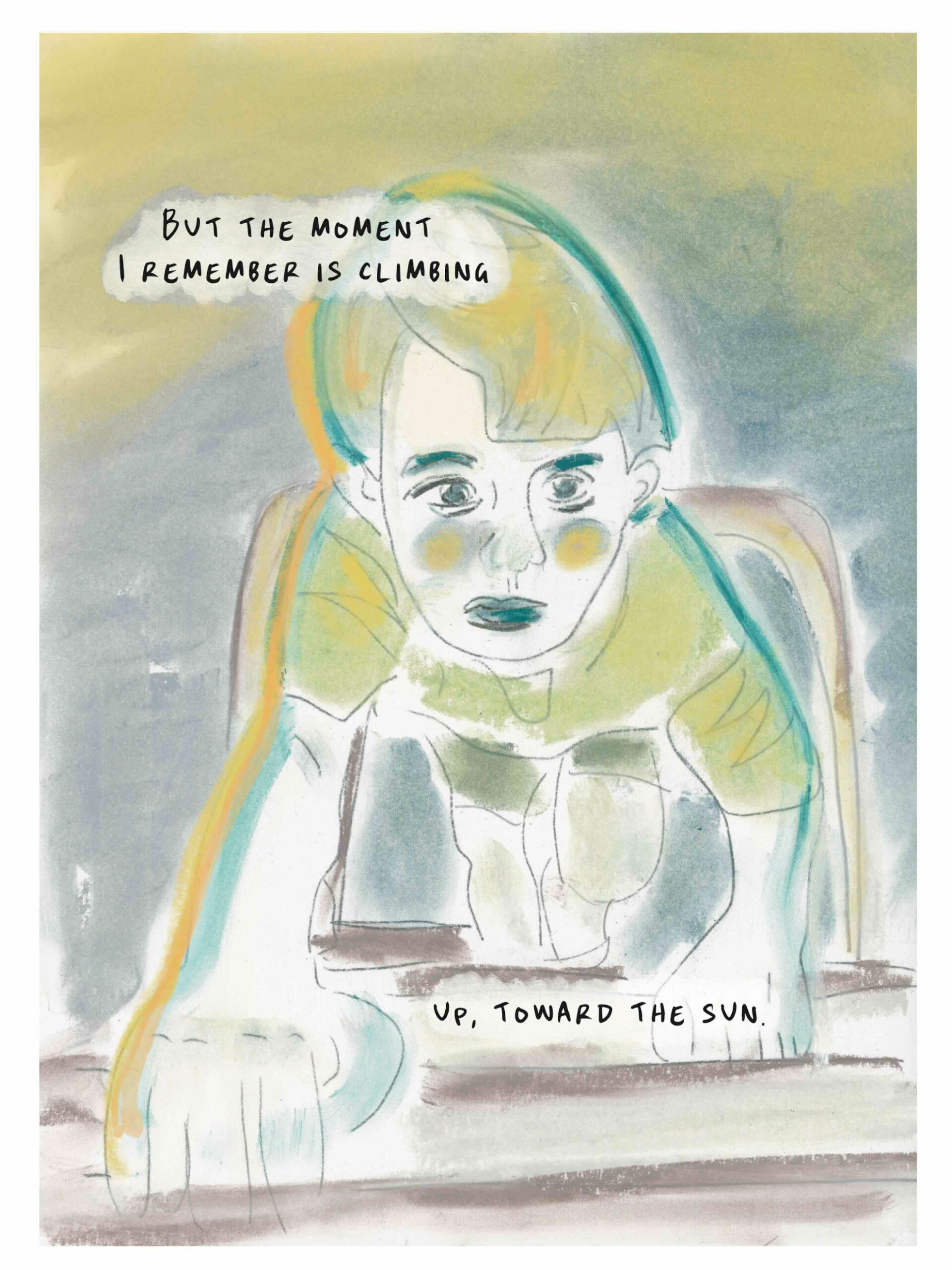

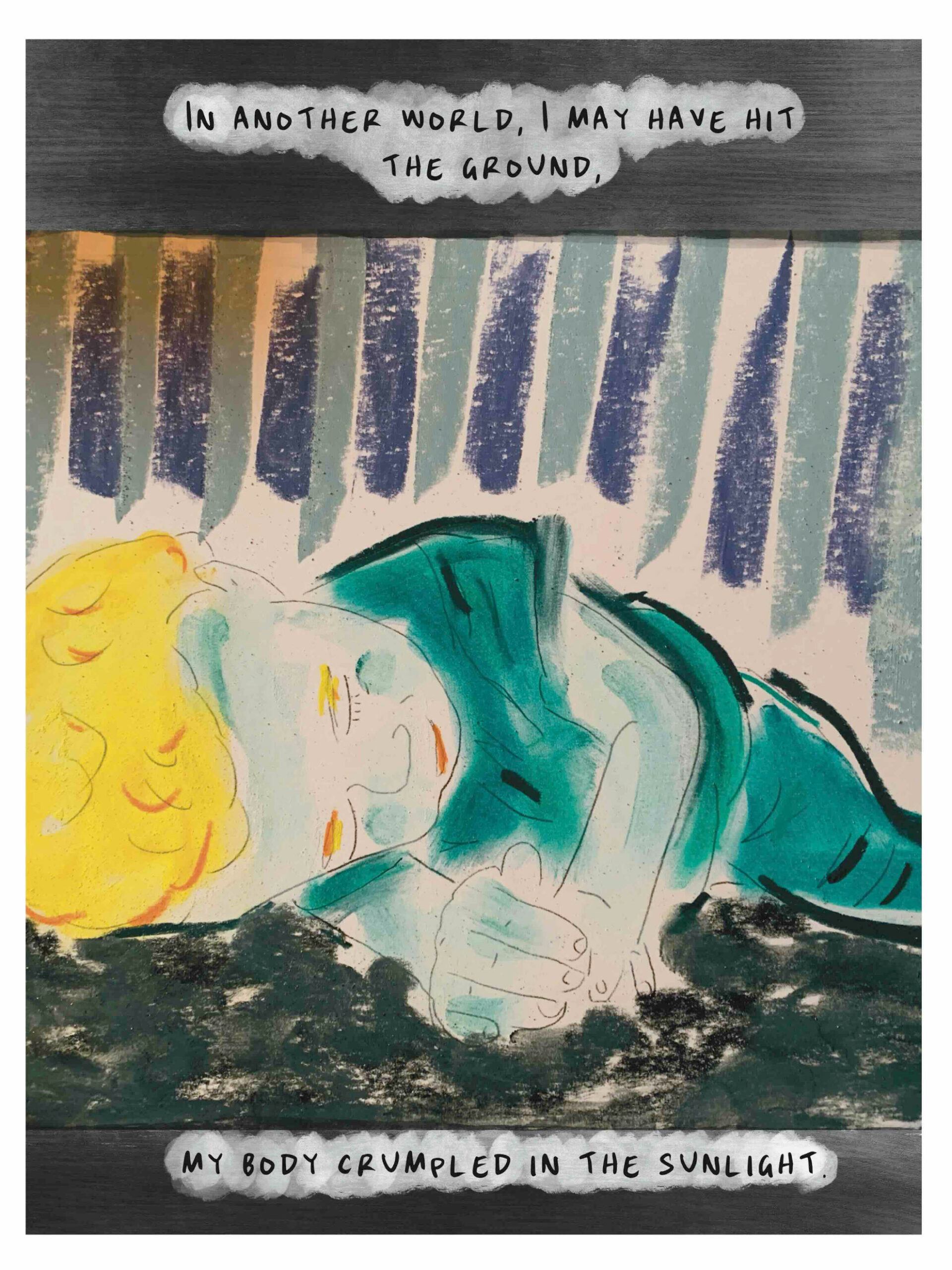

Who was she to me? She was my mother. She carried me for thirty-four weeks in her own body. I was formed from her blood and muscle. For years, she fed me and washed me, carried me on her back and taught me to speak. Whenever I fell, she helped me stand again. Whenever I lost my way, she helped me find a path back to it. She talked to me when no one else would. When I grew old enough to leave home, she watched me go into the rest of my life. When I looked back, she was always there. Until, one day, she wasn’t.

As I faced the mourners of the deceased woman, my face was wet. They were complete strangers to me, I had never met a single one of them until today, but in grief, their expressions were just like mine. I said: She was my mother in the way that all of us are to each other. She saved my life.

Danica Li is an employment and civil rights lawyer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her writing has been published or is forthcoming in the Missouri Review, the Iowa Review, December Magazine, Southeast Review, Cream City Review, Lit Pub, and the California Law Review, has appeared in Best American Short Stories 2023, and has been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize. The first writing prize she ever won was for a short story about unicorns in the fourth grade. Find her at danicaxli.com.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE