Д as in Homecoming

For my friends (and neighbors) in Iowa:

Ben, Anya, Hope, Laura, Echo, Sarah, Jennifer, Abby, Keenan,

Nils, Dallin, Derick, Tyler, Brittney, Allana, and Becca,

with love and gratitude

“Weary or bitter or bewildered as we may be,

God is faithful. He lets us wander so we will know

what it means to come home.” —Marilynne Robinson, Home

“There were several roads near by, but it did not take her long to find the one paved with yellow bricks. Within a short time she was walking briskly toward the Emerald City, her silver shoes tinkling merrily on the hard, yellow road-bed. The sun shone bright and the birds sang sweetly, and Dorothy did not feel nearly so bad as you might think a little girl would who had been suddenly whisked away from her own country and set down in the midst of a strange land.” —L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

I’ve never been to Iowa before, and yet something about the place feels like home as soon as I set foot outside the air-conditioned Cedar Rapids Airport and a hot wave of humid Midwestern August air slams into me. The feeling is simultaneously comforting and unsettling, as déjà vus usually are.

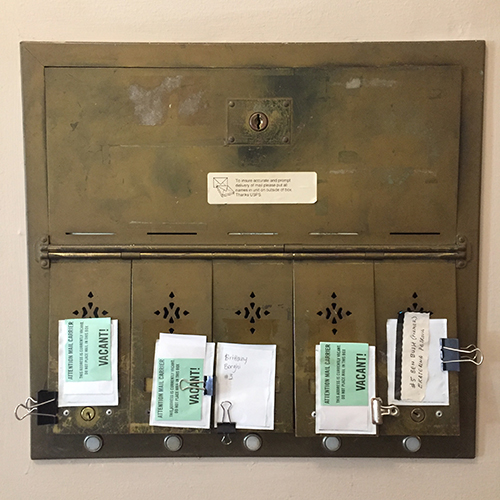

At first, I attribute the sensation to exhaustion from the long journey and a sign of oncoming jetlag, but before I get a chance to fully unpack it, Ben pulls up and picks me up. The feeling persists during our drive into Iowa City, rushing in through the open windows together with the hot air and swirling around the car. We’re headed to Ben’s apartment—I’m taking over his lease and will be living there for the next two years. In just a few days, he’ll be off to Bulgaria on a Fulbright, and staying at my place in Sofia. We make a joke about how we’re swapping lives. But it’s no joke.

Ben parks in front of 725 East College Street and, as we unload my suitcases from the car, I look up and down the tree-lined Midwestern street—rows of houses on both sides, freshly mowed front lawns in front of them, wide paved sidewalks between the lawns and the street—and it finally hits me. It’s not a déjà vu—it’s a déjà vécu. Nineteen years ago, probably almost to the day, having just arrived from Bulgaria, I was unloading my suitcases on a tree-lined Midwestern street just like this one, but in St. Paul, Minnesota, only a couple of hundred miles north of here. It was the first time I was setting foot in the US, as a bright-eyed eighteen-year-old about to start college.

Now, almost two decades later, I’m back in the Midwest and about to start school again. This time around, the school in question is actually an MFA program, I’m probably a little less bright-eyed and certainly a lot less terrified.

Before the semester starts, I’m invited to a welcome event by a lake on the edge of Iowa City. Laura, a new friend from my program, picks me up, so we can drive over together. For a brief second, when she puts the venue’s address into Google Maps, I think I’m hallucinating, but then realize the name of the boulevard we’re after is McCollister, and not Macalester, which is the name of the college I went to in St. Paul. After we arrive, as we make our way over to the venue’s main building, I look up and see, flying overhead, an enormous flock of what Laura tells me are white pelicans, on their way from Minnesota to Mexico. The image of the birds, migrating from their summer home to their winter one, imprints on my mind, and the strangely comforting thought of them flying south in the fall, then back north in the spring, year after year, stays with me for a long time afterward.

Back when I was an undergraduate student, so much about my life in the US seemed new and strange that I very much felt like I was living in a foreign country. Now that I’ve come back, many of those very same things feel cozy and familiar. Most of them are so ordinary, they hardly seem worth mentioning: the shape of light switches and the way they feel between my fingers when I turn them on and off, for instance, or the smell of laundry after it comes out of the dryer, the ringing signal when I make a phone call, the screech and slam of the screen door to the back porch, the taste of blueberry pancakes with maple syrup on weekends, the wide open late-summer skies at sunset, or the distant sound of freight trains in the middle of the night.

These sights, sounds, smells, and sensations continue to accumulate over the following days and weeks, and they keep adding to my feeling of having returned to a familiar place. A couple of months after my arrival, I’m walking by the golden-domed Old Capitol building in the middle of campus, which is just a few minutes away from my apartment, when a newly installed sign of enormous yellow letters stops me in my tracks. It says HOMECOMING. Although I know it’s referring to an American university tradition featuring marching bands, parades, and football games that I feel no connection to, I can’t help but think that in some way, the sign is also for me, that in some inadvertent way it is also commemorating my own sense of having come home.

But besides the comfort brought on by my daily encounters with familiar tastes, noises, scents, and sights, there is also something else, something much more profound, that makes Iowa City feel like home. Back when I was a college student at Macalester, my daily existence was carried out almost entirely in English, which at the time still felt like a relatively new, still foreign language I’d only learned recently. During those four years of college, I would often spend weeks, and sometimes even months, without writing, reading, or even uttering anything in Bulgarian, except for the very occasional, very quick—because they were so expensive—phone calls with my parents and the only slightly more frequent, homesick-ridden emails with family and friends, written in Bulgarian but with Latin letters (Mnogo mi lipsvate!). Cyrillic keyboards used to be impossibly difficult to install.

This time around, however, Bulgarian is very much an integral part of the fabric of my daily life in Iowa. To some extent, because I now can—and do—make free unlimited phone calls to family and exchange regular instant messages with friends back in Sofia. But more importantly it’s because, as a student in the Translation Workshop, I’m constantly engaging with the Bulgarian language, reading it closely, thinking about, exploring and discussing its intricacies, working on bringing it into English. By this point, nearly two decades later, my relationship to English, my so-called “target language,” has also evolved significantly—it’s worked its way up to an equal, though not quite symmetrical, footing with my Bulgarian, and it often takes precedence in my thoughts, reveries, and reflexes. Switching between the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets has become as effortless and instantaneous as pressing the Globe key on the keyboard, both literally and metaphorically. It gradually dawns on me that it’s precisely this dual existence, this daily practice of living actively and fully in both languages, regardless of my physical location on the actual globe, that feels like home.

Perhaps as a bizarre but natural extension of all this, I also discover it’s possible to feel at home and homesick¹ at the same time. The realization strikes me during the spring of my first year in Iowa City, while I’m browsing around Artifacts, one of my favorite shops in town. Although its selection of antiques is enviably diverse, ranging from an undated porcelain statuette of Saint Christopher made in Italy to Moroccan rugs from the ’70s and everything in between, I’m nevertheless taken aback when I stumble upon a framed print of Sofia’s most recognizable landmark—the golden-domed Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. A fifteen-minute walk from my apartment, it looms large and squat in the very center of Sofia, where the roads are paved in the yellow cobblestones, which have become another major symbol of the city, although in the print they appear covered in snow.

The print is the kind of predictable, ubiquitous souvenir sold in every tourist shop around Sofia and the sort of kitschy artwork I’d immediately, and snobbishly, dismiss if I encountered it back in Bulgaria. But here—in a musty, cluttered shop 5,340 miles, an ocean, and a continent and a half away—it’s all I can do to not immediately buy it and hang it over the writing desk in my Iowa apartment. Twenty-five dollars for a piece of home seems like a steal.

A similarly irrational feeling arises in me a couple of months later, as I board the plane at Cedar Rapids Airport to fly back to Sofia for the summer. I feel as though I’m leaving home and—paradoxically, at the very same time—heading home. It makes me think of the pelicans I saw in the fall—they’ve probably just made their way from Mexico back to Minnesota, without, I imagine, much concern about which of the two places is their “real” home. As if I need to be hit over the head even harder, my neighbor Anya has given me a book to read on the long series of flights and layovers connecting America’s Midwest to Europe’s East: it’s a novel by Marilynne Robinson, who taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop for 25 years, until just a couple of years ago. The book is called Home. By the time I reach Sofia, I’ve devoured it.

The fictional Iowa town of Gilead in the novel has nothing in common with the real-life Bulgarian capital of Sofia, just as I hardly have anything in common with the character of Glory who “returns home with a broken heart and a turbulent past.” And yet, something about the description of her (and her siblings’) homecoming resonates with how I’ve previously felt (and, as it turns out, will feel) about going back to Sofia: “The town seemed different to her, now that she had returned there to live. She was thoroughly used to Gilead as the subject and scene of nostalgic memory. How all the brothers and sisters [ . . .] had loved to come home, and how ready they always were to leave again. How dear the old place and the old stories were to them, and how far abroad they had scattered. The past was a very fine thing, in its place. But her returning now, to stay, as her father said, had turned memory portentous. To have it overrun its bounds this way and become present and possibly future, too—they all knew this was a thing to be regretted.”

At that point, though, there is nothing for me to regret—not yet, anyway, since I’m only returning to Sofia for the summer and considerations like those described by Robinson are either behind me, or, as I will eventually discover, ahead of me.

But the home-themed leitmotif also extends into my sojourn, as temporary as it may be. My arrival in Sofia coincides with the official launch of a project I’ve been involved with from a distance, entailing the installation around the city of a dozen or so benches shaped like the Cyrillic letters that don’t have typographic equivalents in the Latin alphabet. Each bench is accompanied by a poem that in some way relates to its corresponding letter, and over the past few months in Iowa, I’ve been working on translating some of the poems into English. It’s an endeavor that seems doomed to fail by its very essence—since the very thing at the center of each poem doesn’t even exist in the receiving language—but that doesn’t mean I haven’t given it the proverbial old college try. Some of the resulting translations are, in my opinion at least, rather successful; others, admittedly less so.

One of the poems, by Krassimira Djissova, is originally called “Дом,” which is pronounced almost like “dome” and literally means “home”—and so “Home” is how I decide to render the title in English. I’m satisfied with my decision until I see the bench that goes with the poem in person, on a side path right by the famous yellow cobblestones, and the deficiency of my translation becomes quite apparent. In contrast to the H of “Home,” which doesn’t resemble a house by any stretch of the imagination², the letter Д, especially when four-dimensional and made of wood, looks like a miniature house with a slanted roof.

In retrospect, it occurs to me that a possible solution may have been to come up with an English title that contains the same root as the Bulgarian word дом (and, not incidentally, the English “dome”), which is obviously borrowed from domus, the Latin word meaning “house,” “home,” or “native place.” So—to the guaranteed outrage of some conservative readers—a better choice, conceptually if not semantically, may have been to translate the poem’s title as “Domicile,” or some other related English word containing the domus root (“domestic,” “domain,” and even “condominium” come to mind). This approach would have had a couple of advantages. Firstly, although typographically different, the Cyrillic Д and the Latin D share the same sound—already a small feat. A second, less obvious but just as important, consideration is that the letter D, like its Cyrillic “equivalent,” has a shape that could also be likened to a dome, albeit a sideways one, or—with a bit of imagination—even to the kind of home we all dwell in for up to nine months before coming out into the world.

The letters D and Д are, in theory at least, as incongruous and mutually illegible as the cities of Iowa City and Sofia. But in practice, I feel equally (though not identically) at home in both cities, just as I’m able to read both letters with equal confidence and employ both languages to which they belong with equal (un)ease. And yet, as I see it, the Bulgarian letter has a significant advantage over its Latin doppelgänger. While D resembles a sideways dome or the “roof” of the womb we can never return to, the letter Д—thanks to the two descenders that extend below its roof-like top part—looks like a house that can walk. Also known as “feet,” these descenders seem like the perfect embodiment of (the possibility for) mobility, which has become an essential element in how I’ve come to understand, define, and experience the concept of home over the years: as something fundamentally movable; something that can travel, relocate, be at two places at once; something I can leave and then return to; something that even when fixed in a single place contains fragments of other places.³

Eventually, my program in Iowa ends, and I do return to Sofia and its very own yellow cobblestones (which, rather tellingly, turn out to have actually come from elsewhere⁴).

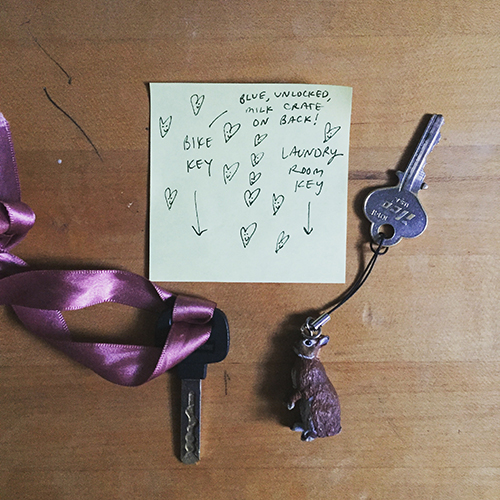

Just a few months later, though, I get the chance to go back to Iowa City for Thanksgiving. I see old friends, visit old haunts (including a long browse at Artifacts), even get to do laundry and ride around town on a bike that my friend Abby has lent me—and at first, it all feels like another homecoming.

But on my second or third night in town, on my way to Laura’s house for dinner, I bike past my old place on 725 East College Street. There’s something uncanny—unheimlich, or literally “‘un-homely,” as they say in German—about seeing the lights in the windows of my old apartment are on, though I’m no longer living there. I realize that the place—the apartment, but also the town, and by extension even the Midwest and the US as a whole—is no longer a home, and I’ve now reverted to being a guest. Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.

On my desk back in Sofia, where I’m now sitting and writing this, I keep a snow globe with an Iowa tornado. It’s the kind of kitschy souvenir I’d usually snobbishly dismiss, but this one has great sentimental value. It’s a gift from my friend Becca who gave it to me as a keepsake to remind me of the time we got evacuated from a bar in downtown Iowa City because of an approaching tornado. Inside the snow globe’s sphere is a house swept up in a tornado, and whenever I look at it, it always makes me think of Dorothy of Oz. As a child and a young adult, the idea of having my home swept up and finding myself “set in the midst of a strange land” used to seem terrifying. Over the years, however, it has grown not just significantly less scary, but even, and increasingly so, quite appealing. Unlike Dorothy, for whom “there’s no place like home,” I’ve come to discover that there can be, have been, and probably will be a few places that to me do feel very much like home(s). And just so I don’t forget this, next to the snow globe on my desk I keep a paperweight that also has a globe in it, but that one depicts the world.

¹ The word “homesickness” is a calque of the German Heimweh (from Heim, meaning “home,” and Weh, meaning “woe” or pain”), which is usually used in the phrase “krank von [meaning, “sick with”] Heimweh.” The word for the phenomenon in Bulgarian—носталгия (nostálgiya)—is borrowed from the compound coined in 1688 by the Swiss medical student Johannes Hofer who combined the Greek words νόστος (nóstos), meaning “homecoming” (which— unsurprisingly—was used by Homer in The Odyssey) and ἄλγος (álgos), meaning “sorrow” or “despair.” (Interestingly, the meaning of the related adjective νόστιμος (nóstimos) evolved, so that in modern Greek, it signifies “tasty,” “delicious,” or “cute.”)

² What the letter H does resemble is a ladder, and—if anyone cares to notice—it acts as quite a nice visual for the poem’s opening line, which in my translation reads: “The staircase to the last floor ends in mid-air.”

³ Coincidentally, one of the most intriguing characters in Slavic folklore, the crone known as Baba Yaga, lives in a house on legs (chicken legs, to be more specific). A BBC article about an anthology of stories dedicated to her (“Baba Yaga: The greatest ‘wicked witch’ of all?”) highlights the character’s duality and moral ambiguity, describing her “sometimes as an almost-heroine, sometimes as a villain.” One of the contributors to the anthology, the author Yi Izzy Yu, sees Baba Yaga as a proto-feminist icon that “challenges conceptual categories at every turn. Even her home is both house and chicken, making her, yes, housebound in a sense, but not in any way ‘tied down.’” Needless to say, I can relate.

⁴ Although the yellow cobblestones have become one of Sofia’s most recognizable symbols, they were in fact—and rather tellingly!—cast in Budapest, then imported to Bulgaria and installed over the capital’s central boulevards at the beginning of the 20th century.

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary translator, bilingual nonfiction writer, and amateur photographer. Her collection of travel essays, Thingseeker: 44 (Un)Usual Objects from Near and Far was published in 2021. Her work has appeared in Bulgarian and English-language publications, including Asymptote, Words Without Borders, and European Literature Network. She holds an MFA in Literary Translation from the University of Iowa. Currently based in Sofia, she practices and occasionally teaches translation, writes a column on fascinating etymologies for the Bulgarian independent media Toest, and is at work on a collection of essays and photographs, titled Here & Elsewhere, about travelling, translation, and belonging.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE