Chunksi

I.

Four friends bake in the sun, four reservation princesses wearing sagging basketball shorts and white tank tops, waiting for something to happen, anything, anything at all to break the monotony. It is midday and too early for the spectacle of someone kicked out of the casino for drunkenness. Too early for ejection due to violence, for freak out over a social security check gone too soon. Too early, but if they sit long enough, these Shakespearian tragedies are inevitable. So they wait.

Four res princesses, in a kingdom that begins atop a picnic table outside the casino/gas station/quick-mart, a kingdom that extends beyond the overflowing trash bins and cracked asphalt, beyond the idling trucks and the cars filling up at the pumps, and ends where the parking lot becomes the on-ramp to the highway, and the highway becomes escape.

Her name is Rachel. She is 11, and already she’s acutely aware of the insufficiency of this place.

“Dang, it’s hot,” says April Rose, and Rachel and Demora and Howa (short for Howasapa) and the wind all agree. But the wind says nothing, only blows dry and spiteful over the casino, a casino built cheap like government housing. Over the picnic table indelibly marred by the bloody vomit of Indians who traded their livers for fleeting moments of forget. Over the South Dakota town on the other side of the highway, a town already old and forgotten when it sprouted up over a century ago, on a reservation where despair reigns and the ceiling for success is the purchase of a flatscreen TV for a squalid living room, or a not-yet-repossessed pickup truck parked in a front yard, majestic in the grass like a lion on the savannah and complicit in countless DWIs. The wind blows dry and spiteful over it all.

Rachel holds Demora’s long, silky black hair in her hands and braids it meticulously, an act of kindness, an act of love. “Man… geez,” says Demora when strands get caught in her bracelet. “Don’t pull my hair out.” April Rose and Howa share a giggle. Rachel apologizes. An eighteen-wheeler groans its way out of the parking lot, kicking up dust as it makes a break for it.

“Heya,” says Demora. “My sister called that the wakpa.” She extends a finger at the highway. Rachel doesn’t know what that word means, but she knows the highway is Interstate 29, knows that civilization in the form of Fargo, North Dakota, is a couple hours north, and Watertown and Sioux Falls is an equally tedious ride south.

Rachel doesn’t know what that words means, but her friends do, because they are all darker, full-bloods to her half-blood, each born on the res and far more Indian. She envies them for the language they share. She envies them for their fathers locked away in federal pen, or dead or nonexistent. She envies them for their mothers lost to drink or pills, or simply gone. It is almost an embarrassment that her own red father and white mother reside under the same roof.

Her friends, they all know what wakpa means. But she doesn’t ask them. She doesn’t want to remind them of her differences. How much unlike them she is not.

“Wakpa means river,” Howa whispers into her ear. An act of kindness, an act of love.

A woman approaches from across the parking lot, older but not yet old, with bright red lipstick, worn jeans and scuffed boots. Like Rachel and her friends, she has walked from town, a distance of a few miles but a not uncommon practice for those with nothing and nothing to do. The woman is closer now, close enough for Rachel to see the dark blue ring around her eye, close enough for Rachel to discern the remnants of violence and the shame on her face. She keeps her gaze from meeting Rachel’s and holds her head high—typical proud Native woman. The woman walks past the picnic table and reaches for the door to the gas station.

Demora calls out to her. “Auntie, buy us something to drink, hey?” Rachel knows they’re not related, that Demora has probably never met this woman before. But on the res, any older woman is Auntie, just as any older man is Uncle.

The woman finally looks at all of them. Shakes her head and says “shit” with a hiss, as if such an act would be beneath her. She pulls open the door and goes inside.

The sound of an eighteen-wheeler. The sound of someone slamming their hood down and getting back into their car. The stink of exhaust. Down the side of Rachel’s face, a trickle of sweat. The door opens and the woman is there again. In one hand is a pack of cigarettes. In the other, a paper bag and the unmistakable shape of a 40oz. She stands beside the four of them and the cigarettes go into a tattered purse. Off comes the cap. She puts the bottle to her lips, tilts her head back, and takes a long drink. Rachel watches the sagging skin below her chin move in its own rhythm. When she hands the bag to Demora, there’s a collective sound of appreciation.

Around goes the bottle. Gulps and winces at the taste of the cheap beer.

“What are you girls doing here anyway?” says the woman. “Jus’ getting into trouble?”

“Heya,” says April Rose. “Doing nothing. What are you doing, Auntie?”

“I’m about to ride the wakpa,” she says.

“Damn,” says Demora. “We were just talking about that. Why is called the wakpa?”

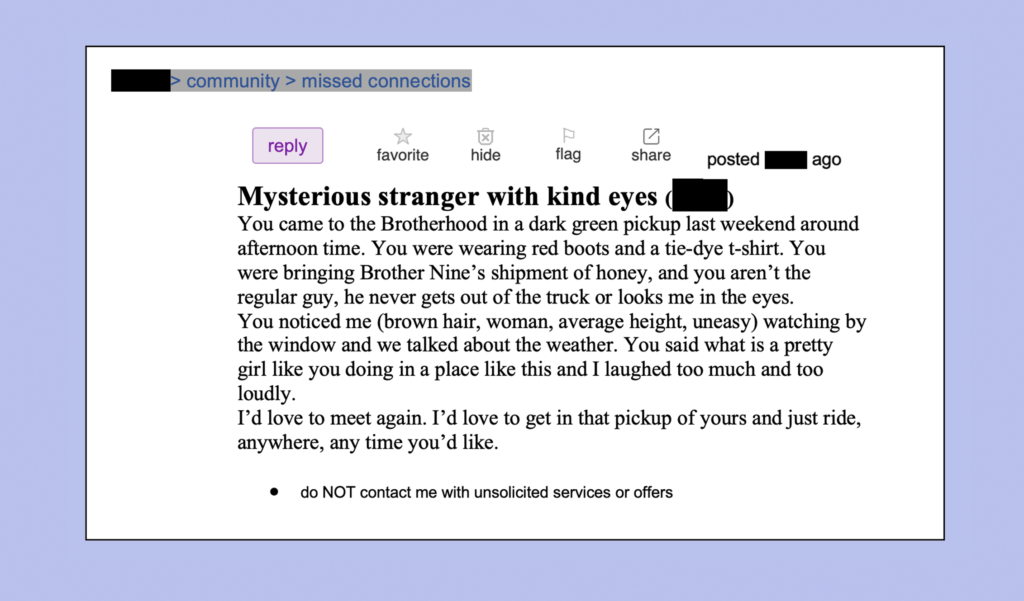

Another long drink from the bottle that makes the skin below her chin move, and the woman says, “Because it’s like a river. You can ride it away from here, maybe far away.” Her voice trails off, and her eyes go to the parking lot. “But you have to know how to swim, otherwise you drown.” She continues to stare, and Rachel follows her gaze. There’s a car there, a battered old Cadillac with tinted windows, parked away from the gas pumps. Idling. Rachel thinks of the coyotes that prowl the woods near home, and how children can’t play outside after dark lest one of them slink out of the tree line and drag a hapless kid away.

“Why are you going, Auntie?” says April Rose.

“Auntie Wana-yi said it’s time,” says the woman. Her voice is solemn.

“Shit,” says Demora. “Auntie Wana-yi spoke to you?”

“You seen her?” says the woman, her eyes narrowing.

“Yeah, I seen her. She didn’t say nothing, though. She was just brushing her hair.”

The woman makes a clucking sound, the sound of skepticism, but she watches Demora, and her expression grows into one of sadness. A last swig from the bottle, and she reaches into her purse, producing a cigarette and lighting it. A long drag, then another, and another. Her eyes are back to the battered old Cadillac. To the coyote, waiting to drag her away. “You girls mind yourself,” she says, her words a kind of goodbye.

Rachel watches her go in silence, watches her worn jeans and scuffed boots as she crosses to the edge of the parking lot, a tattered woman all used up, and Rachel swears to never become her. When she gets to the Cadillac, she reaches for the door behind the driver seat. Pulls it open and disappears inside. The four res princesses watch in silence as the Cadillac lumbers out of the parking lot, finds the on-ramp to the highway, and accelerates into oblivion.

*

They walk back to town, and Rachel catches a ride with an uncle headed out towards a distant cluster of tribal-owned houses, one of which is her home.

Outside, on the hood of a long dead car beside the house, is a wolf—Waji, her family’s pet, and their answer to the coyote problem. Waji raises her head.

Rachel greets her with a hello and a gentle rub, and walks into the house just as the sun begins to fall behind the hills to the west.

Her mother is setting the table for dinner. When she sees her, she pulls Rachel in for a hug and plants a kiss on her forehead. Tells her to wash up, let her father and brothers know it’s time to eat. Soon, everyone is seated, and as spaghetti is divvied up onto plates, her father’s voice booms.

“How was my chunksi today?” he says, using a word Rachel does know; chunksi means daughter. “Stay out of trouble?”

She tells him she did stay out of trouble. As the baby of the family, that’s the entirety of her share of the conversation. But she doesn’t mind, because she is happy.

The rest of dinner is spent with her older brothers talking and joking, and her parents laughing and chiming in. Eventually, her father asks them to sing. “Remember that tribal veteran honor song?” he says. “Do that one.” Four sets of male hands begin beating out a tempo on the table. The house fills with the sounds of tradition.

Her parents don’t work, but between the prize money her brothers sometimes win at singing and drumming competitions at powwows, the money she sometimes wins dancing in her jingle dress—plus food stamps, occasional visits to the res pantry, and whatever other assistance the tribe offers—her family survives.

After she has helped wash the dishes, her mother burns sweetgrass to cleanse the house while her father sits in the living room with her brothers, all of them focused on the Playstation. While they play, Rachel thinks of the woman and the Cadillac. Surely, if this had been her home, the woman would never have left.

When her parents go to bed, she asks her brothers what wana-yi means. Unlike Rachel, they are being taught the language of the Dakota Sioux—by the teachers at school and by her father, knowledge everyone thinks she would squander.

River, the youngest brother, older than her by just a year, doesn’t look away from the TV screen. None of them look away. “Wana-yi means ghost,” he says.

II.

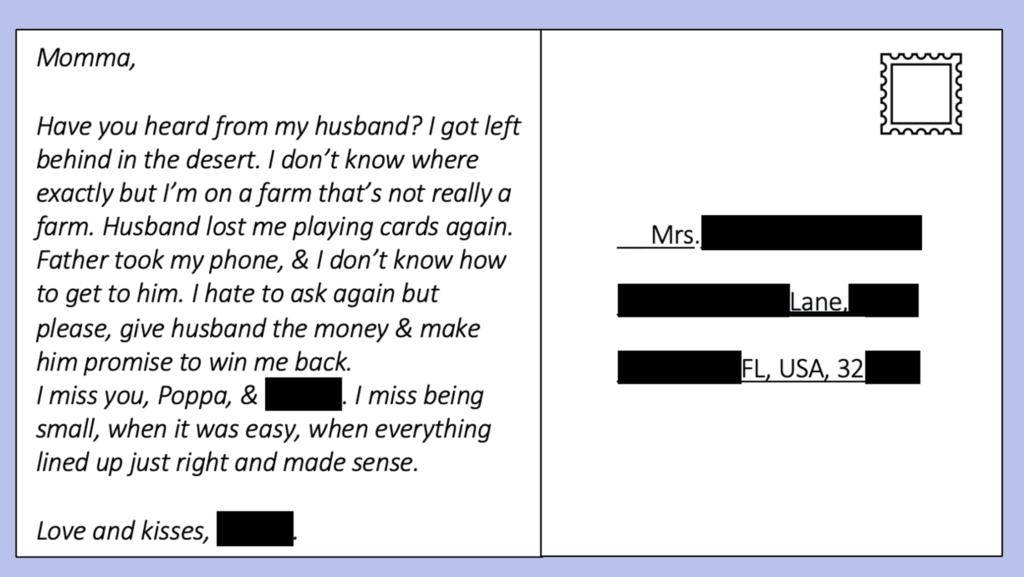

A white woman disappears and it’s a crime. A noteworthy thing. A cause for concern. But change her skin tone just a bit, transform her paleness into an earthy red, and the disappearance is a non-event. The person gone, she doesn’t matter. It is debatable she ever did. This is why Rachel never learns what happens to the woman who left in the Cadillac, why Rachel never learns where they find her body.

This is why, after months of sitting on that picnic table, watching lone res women climb into strange vehicles and vanish down the river, Rachel never knows what becomes of them. She likes to think that the bruises around their eyes have eventually healed. That they have found safety.

Rachel is 12 now, and her home has grown quiet and lonely. Her brothers are away at the Flandreau Indian School, a boarding school a few hours south on the wakpa. It was a tough decision for her parents to send them away—she heard them fight about it. But the education is supposedly better than the one offered at the Tiospa Zina Tribal School, so off they went.

The Tiospa Zina is where Rachel goes, where she takes remedial classes, because her teachers would rather treat her as stupid than acknowledge her dyslexia.

“Heya,” says Demora. “That thing freaks me out.” She is staring at Waji, who lies on the roof of the long dead car. It is fall, and the air alternates between stifling hot and shiver-inducing chill depending upon if clouds drift in front of the sun. Waji watches the tree line, panting, her tongue lolling out, while Rachel, Demora, April Rose and Howa sit on a patchwork of rusted and tattered lawn chairs.

“It’s just a wolf,” says April Rose.

Demora makes a face. “What kind of Indian keeps a wolf as a pet?”

Howa is the same as she ever was, but Demora and April Rose have taken to wearing skirts and, on occasion, make up—habits so alien to Rachel they border on betrayal. Rachel knows Demora has been seeing a boy from the white high school in town (whose football team is inexplicably called “The Redmen”). Rachel doesn’t know who April Rose is seeing, but she suspects there is someone, too.

“Rachel!” her mother calls out. Her parents are leaving the house and heading to the van parked on the street. As usual, her father’s mirrored sunglasses make his expression impossible to read, but her mother’s tone says it all. She is angry. “We gotta go get the boys. Mind the house. Don’t cause no trouble.”

As they drive away, Rachel thinks of how anger is the only tone her mother speaks to her in nowadays. Thinks of how her father doesn’t call her chunksi anymore.

When it is clear Rachel’s parents aren’t doubling back, Demora reaches into her knapsack and pulls out a joint. “Cocha!” she says with a grin. Everyone laughs.

In no time they are high, and the four of them point out the different animals they see in the shapes of the passing clouds.

Rachel is high when Howa talks about how her grandmother used to take care of her, but more and more she takes care of her grandmother.

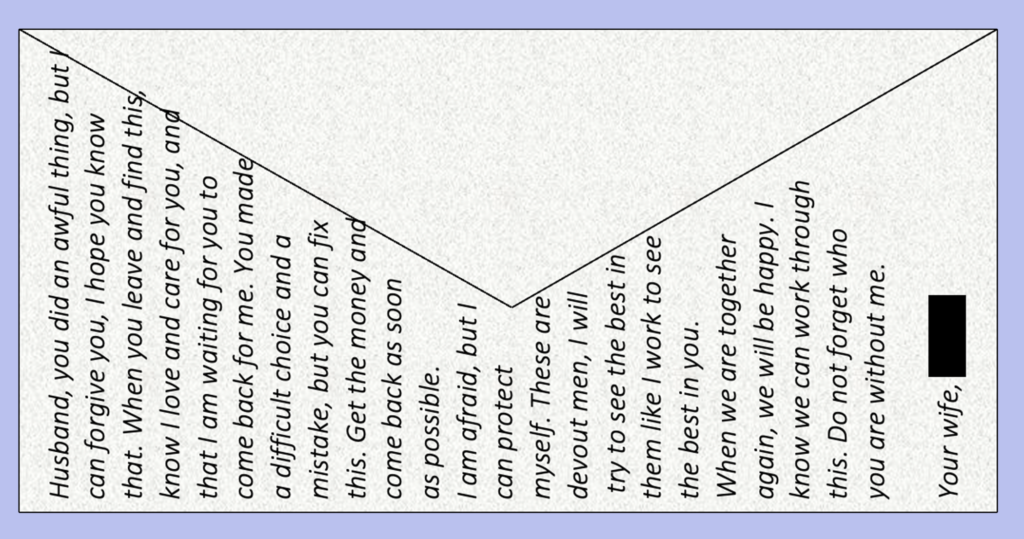

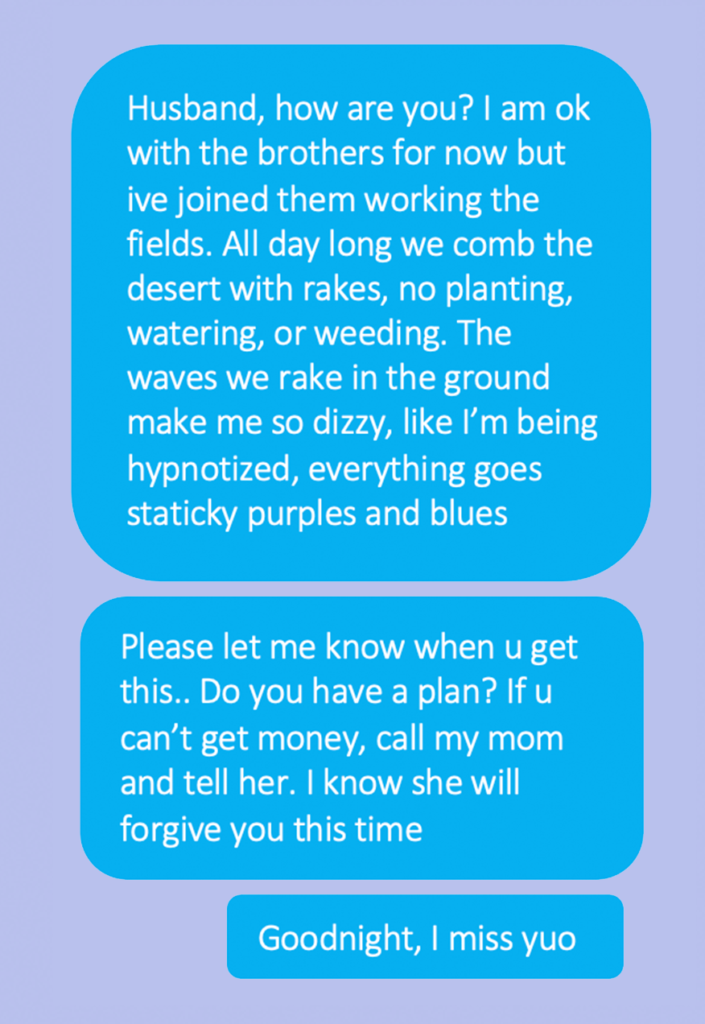

Rachel is high when Demora talks about riding the wakpa with her boyfriend, how Auntie Wana-yi spoke to her and said she was ready.

Rachel is high when April Rose says nothing at all, only weeps in silence. Rachel reaches out and holds her hand. An act of kindness, an act of love.

Rachel is high when Waji jumps down from her spot on the roof of the dead car and nuzzles her hand for a rub, the wolf’s sudden presence startling everyone, eliciting screams that turn into laughter. Deep, endless, hysterical laughter.

Hours later, after her friends have long since gone home and she is sober, her parents return with her brothers. No one will include her in the conversation, or what’s left of it. She suspects all the words were used up on the ride back. But her father’s silence speaks of disappointment and her mother only calls out her name with anger in her voice and tells her to clean her room, and how can anyone live like this? “You give filthy Indians a bad name.”

Later on, when her parents have gone to bed, her brothers dust off the old Playstation. She asks River what happened at Flandreau. “We were expelled,” he says. “For fighting.”

III.

They say it was an SUV, maybe dark blue, maybe black. They say that Demora Gray Eagle waited outside the casino on Interstate 29 for less than an hour before seeing it at the edge of the parking lot. According to a witness, she walked up, opened the door to the backseat and climbed in. No conversation. No description of the driver. That was the last time anyone saw her.

Her boyfriend tells the police they had broken up the week prior. He’s a junior at the white high school in town, and no, he has no other information to add. His parents chime in, saying if the police have additional questions, they can talk to their attorney. But the police have no more questions. No one has any more questions.

Rachel is 14 now, and old enough to understand that some things cannot be asked or asked for, like why or help.

She is also old enough to understand how after only a few disappointments everything can come apart. She knows this because her oldest brother, Enoch, is arrested for a sexual assault on a school bus, and after his conviction, he is carted off to a juvenile detention facility in a distant part of the state, where he will stay for the next few years.

Rachel knows this because her other brothers, River and Leonard, drop out of school altogether, and there are no more family dinners at the table and no more songs.

She knows this because her mother screams at her father more and more. Screams at her brothers. Screams at her.

She knows this because one spring night there is a great ruckus outside, and her father and River and Leonard run out the door with knives, shouting. When they return, River has blood on his t-shirt. “Waji’s dead. The coyotes ganged up and got her.”

No one cries for Waji but Rachel, quiet tears shed when she is alone in her room. No one cries for Enoch or Demora but Rachel.

Now the house is truly mirthless and sullen, and no amount of smoldering sweetgrass can cleanse the bad spirits.

“I hate this place,” says April Rose. She isn’t talking about where they are sleeping tonight. Tonight, while Rachel’s parents think she is at Howa’s house, the three remaining res princesses are camped out in Sica Hollow, a haunted state park near town. According to local lore, the ghosts are of white folk and the Indians who murdered them roughly two hundred years ago, so to anyone white, Sica Hollow is a place of terror; to anyone is red, it is something else entirely.

Their camp is in the middle of a field thick with tall grass, atop a plateau. Above, a canopy of endless stars; below, the woods, trails, streams and gurgling springs that make up most of the park. They don’t dare make a fire, but it isn’t cold, and anyway, it is doubtful they would mind if it was, for Howa has brought some of her grandmother’s pills. They each swallow two, and soon they are warm and fuzzy.

From somewhere nearby, the hoof beats of horses that roamed these hills generations ago.

April Rose talks about her cousins, who live in a trailer near Enemy Swim and have a child together, a child whose conception and birth sent the father to prison for a few years. When he got out, they made that trailer into a happy home—happy by res standards at least. “I hate this place,” she says, and Rachel knows she means this town. This res. This life.

From somewhere nearby, faint songs of victory, sung by Indians who thought victory over the white man was all they would ever know.

Howa stares at her hand as if she has never seen it before. Says, “I don’t want to leave my grandmother, but she claims it’s important that I go. That if I go to college and never come back, it’s a good thing, because I’ll have chosen my own path.”

The three of them fall asleep huddled together.

Later on, Rachel wakes to the sound of someone humming a gentle tune, in the darkness on the path they took to get up here. April Rose and Howa remain deep in slumber, curled up under the blankets. Howa is snoring.

Rachel disentangles from their limbs and still neither stir, not when she slips on her sneakers, not when she rises, not when she follows the path to the sound.

She does not walk far. At the edge of the plateau, where the grass of the field meets the trees that line the sloping woods, rests a fallen log. There, a woman sits, beautiful in a multicolored dress and a shawl. She brushes her long, flowing black hair in easy, thoughtful strokes. The woman looks up at Rachel.

Rachel knows who she is.

“Hello, Rachel,” says Auntie Wana-yi.

IV.

She is in rehab when she gets the news that April Rose Crow Dog drank a bottle of Jack and a bottle of vodka, went to sleep and never woke up again. Another Indian who drank herself to death, another friend gone, and she is sure she has no more tears left to shed.

Rachel is 16 now, and bitter. Enoch remains incarcerated and Leonard has moved to Sioux Falls to start a family of his own, but River still lives at home, and he doesn’t bother to conceal the track marks on his arms. Her mother and father say nothing about that, yet when Rachel is caught with pills, she is sent away to an inpatient clinic south of Watertown, and now must deal with the hassle of outpatient treatment in Agency Village three times a week. How is that fair?

“This is what it means to be winyan,” says Auntie Wana-yi. Rachel stands outside the outpatient treatment center, waiting for her ride. The Tiospa Zina High School is across the street, and though Rachel would hate for her sometimes-classmates to see her at the place where Indians go to halfheartedly stop being the architects of their own doom, she takes comfort in the knowledge that they can’t see Auntie Wana-yi. No one can. “This is what it means to be a Native woman,” says Auntie Wana-yi.

Rachel waits for her to go into one of her stories, something about how when the menfolk would leave for hunting parties, it was up to the womenfolk to do everything to keep the camp alive, including fight off enemy warriors. The typical story of the strength Native women must have. But the Wana-yi in the multicolored dress and shawl says nothing, only watches. Which to Rachel is worse. It feels like judging.

A Ford Escort with no front bumper and a door the wrong color putters up the street. It’s Howa, her ride. Rachel slides into the passenger seat. The car reeks of the habits of its previous owners—Howa bought it from someone who bought it from someone who bought it from someone else—but there are personal flourishes, like the leather dreamcatcher dangling from the rearview mirror, and the Dakota phrase Matuwe Sdodwakiye written in marker on the dashboard. Rachel traces her finger over the words.

“‘I know who I am,’” Howa interprets, and Rachel repeats it. Howa hits the accelerator, taking the car back onto the street.

Rachel notices a sticker on the door to the glove compartment, a fish with whiskers splashing in water. She asks if Howa likes to go fishing, if it’s a new hobby or something.

Howa looks at her like she has asked something silly. “That’s my name.”

Rachel doesn’t know what she means.

“Howa? Howasapa? Howasapa is ‘catfish,’” she says. “All this time and you didn’t know that was my name?”

In the backseat, Auntie Wana-yi shakes her head.

On the seat between them lies a thick SAT prep book, the key text for a course Howa takes three times a week at the white high school. “Am I driving you home?” she says. “If so, we have to hurry. I’m going to be late to class.”

When Rachel had asked for this ride, she didn’t realize it was going to cut into her friend’s study time. She didn’t realize how she could be harming Howa’s future, harming her own escape.

“Am I taking you home?” Howa repeats. Rachel tells her she needs a moment to think.

And so Rachel thinks about her home, and her mother and father, how their fights have cooled into a shared existence of silent hostility. Rachel is certain that if not for her, her parents would go their separate ways, and maybe that would be for the best.

She thinks about her brothers and what has become of them.

She thinks about what became of Waji. About the happiness and safety she once felt, so long ago, when she was a different person—an innocent, young res princess worried about coyotes in the woods.

Then it dawns on her.

“Heya, here it comes,” says Auntie Wana-yi.

The coyotes were in Rachel’s house all along.

She tells Howa to drive her to the casino. Her father has taken a job at the tribe’s sister casino further north on the highway, a bigger, grander place with a hotel and restaurants. Her father washes dishes at one of them. Rachel tells Howa that if she drops her off, she will take the free shuttlebus and visit him.

“You sure?” Howa asks. Rachel tells her yes, she is sure.

When the car eases to a stop in the parking lot of the casino, Rachel opens the door and puts a foot out, but then leans back in and gives Howa a hug. Tells her she’s always been a good friend.

“Cocha, you’re being dramatic,” Howa says. Still, she hugs Rachel back, and when Howa drives off, Rachel watches her go.

Auntie Wana-yi stands beside her. Tucked in the cord belt around her waist is a brush carved of bone, and she pulls it out and begins running it through her long hair.

The wind blows dry and spiteful, and Rachel surveys her kingdom—the picnic table, stained and empty. The overflowing trash bins and cracked asphalt. The eighteen-wheelers, building up their courage to leave. The strangers at the gas pumps, just passing through.

At the edge of the parking lot, a battered Lincoln Continental idles.

“Why am I doing this?” she asks.

“Because it’s time, Rachel,” says Auntie Wana-yi. “There’s no strength in staying, and to go is an act of kindness, an act of love.”

Rachel stares at the Lincoln Continental. At the tinted driver’s side window, the driver she cannot see. She takes a step towards it but hesitates.

“Go on,” says Auntie Wana-yi. “You know how to swim.”

Rachel stands there for a moment, considering the words. Yes, she is sure she knows how to swim, so she walks toward the idling car, and then her hand is on the door handle.

And she is pulling it open.

And she is sliding into the backseat.

And then she is in the river.

Jim Genia—a proud Sioux—mostly writes nonfiction about cagefighting, but occasionally takes a break from the hurt and pain to write fiction about hurt and pain. His book, Raw Combat: The Underground World of Mixed Martial Arts, was published in 2011 by Citadel Press. His short fiction appears in the Zodiac Review and Electric Spec. Follow him on Twitter @jim_genia.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE