Of the Burning; Or, James Weldon Johnson Investigates the Lynching of Ell Persons

If you would want to know something about the life of a human being, this one named Ell Persons, it would be because you first knew something about his death. And something about the mob who murdered him. I could say that the mob that day was angry but that would be cliché, as in angry mob. And untrue. The crowd was actually quite calm as it played both participant and spectator—judge without jury—in the spectacle it made of burning a man’s flesh.

Or was it a jury without a judge?

If you want to know something about the death of a human being, this one named Ell Persons, here are the facts as we presently know them:

On May 2, 1917, a white, sixteen-year old named Antoinette Rappel was found dead in the woods near Macon Road just outside the city limits of Memphis, Tennessee. She had disappeared three days earlier. Her body exhibited signs of sexual assault, and her decapitated head sat beside her right foot. Investigators claimed that the neck showed signs of being hacked by an axe.

A Black man named Ell Persons lived in a cabin about a half-mile from the crime scene. About 50-years old, he made his living as a woodcutter.

Early assessments by investigators noted that evidence seemed to indicate that the crime began as a friendly encounter. Since it was assumed a white female would never walk alone with a Black male, it followed that the crime only could have been committed by a white male. Nevertheless, police apprehended, interrogated, and released Ell Persons not once, but twice. Abandoning other leads, the police brought him in a third time. Over the course of 24 hours, they gave him the treatment known as the “third degree,” severely beating him until he was left, despite the evidence, with only way out.

He confessed.

The only thing to corroborate Ell Persons’ confession was conjured when police exhumed Antoinette Rappel’s body and took a photograph of her eyes. Basing his findings on a dubious theory promoted by French biometrician Alphonse Bertillon, a police officer reported that, when examining the photograph under a microscope, he saw the last living image Antoinette Rappel saw. Displaying a “frozen expression of horror” (the phrase news reports used to describe her eyes), the officer said he could detect an inverted image of the face of Ell Persons imprinted as if it were photocopied on Antoinette Rappel’s retinas.

Fearing a lynch mob, police escorted Ell Persons to Nashville to await arraignment. On May 21, a group of white men intercepted the train carrying him back to Memphis. The police officers conveniently stood down without resistance. The headline in the Memphis Commercial Appeal the next morning announced Ell Persons’ imminent lynching, almost as if it were an invitation. A crowd estimated to be at least 3,000, including children, showed up near the crime scene. Stands were set up to sell sandwiches and snacks, and a self-appointed master of ceremonies stage-managed the event, as if it were a carnival.

Once Ell Persons was secured to the post erected at the site, some within the mob allegedly complained that too much gasoline had been poured on his body. Their objection was that it would make the fire less painful and his death too quick.

Shortly after Ell Persons died, his body was decapitated and dismembered, hacked with an axe. A number of people swarmed the pyre to grab the parts, as if they were souvenirs or relics.

Newspaper accounts at the time asserted that this was the first lynching in American history carried out in broad daylight and without masks.

Members of the mob drove Ell Persons’ decapitated head to Beale Street in the heart of Memphis—at that time the center of the African American community—and threw it out of the open passenger-side window at a group of Black pedestrians.

As it lay on the sidewalk, photographs were taken of Ell Persons’ head and one of the shots was eventually printed on postcards. The reason we know these photographs existed is because one of them was obtained and reprinted with a scathing editorial in the Chicago Defender, the most popular African American newspaper of the time.

Shortly thereafter, James Weldon Johnson, field secretary of the still relatively new National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), arrived in Memphis and spent ten days independently investigating the crime and its aftermath.

After ten days, James Weldon Johnson could find no material evidence that Ell Persons had committed the crime.

So it was that the mob was quite calm—matter of fact even—as they tied a man to a beam of wood and lit him on fire. Some said Ell Persons didn’t say a word as he burned. Others said they heard something but could not make out the words.

As he walked the smoldering ground, James Weldon Johnson might have heard the echoing of the voice. The voice would have been Ell Persons’ voice whispering out of the burning cords of his own flesh, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

*

Shortly before the lynching of Ell Persons, James Weldon Johnson had written “Brothers—American Drama,” one of his most haunting poems. Written in a Shakespearean iambic pentameter, it is a dramatic reenactment of a scene where a mob interrogates a man before burning him alive. The mob’s monologues are an ominous allusion to the choruses of ancient Greek tragedy, except that in this case their voice unknowingly betrays their own guilt, their own words pronouncing judgment upon themselves. In the midst of the judicial miscarriage, the victim speaks these words, embedded within one of his monologues:

The line echoes the Tetragrammaton, the ancient Hebrew name of God — I A M W H O I A M — Moses before the burning bush, numinous breath animating fire. The line animates its speaker’s imago dei—his face in the reflection of the face of God—in defiance of the mob’s inhumanity. But even to call it “inhumanity” does not seem adequate. Hatred, brutality, violence, atrocity: each word falls silent at the sight of flayed limbs hanging from a tree drenched with gasoline, slow death meant to inflict utmost pain upon a body and a soul.

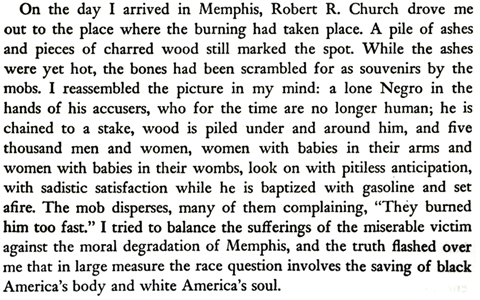

Fifteen years later, on page 317 of his autobiography, James Weldon Johnson would write a paragraph describing the lynching of Ell Persons with an elegiac and terrifying mix of past and present tense.

When I first read the words lying in bed at the verge of sleep, I had to stop reading, wide awake along the edge of midnight. I would not pick up the book again for days. You could say I was brought to the end of reading—its terminus, its telos—the point at which I could only resume my interaction with words by writing some of my own.

In other words, the words you read now.

*

Of writing, the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin once wrote:

For James Weldon Johnson, the moment was reading the news reports of the lynching of Ell Persons, reading the remains of newsprint smoldering with human ash on the cleared ground beyond Macon Road. For me, the moment was reading what Johnson wrote of what he read 83 years after he wrote it, the image still burned in my eye of a teenager’s body facedown for four hours under an unrelenting sun on a street eight miles from where I lived, the next big city up the muddy river from Memphis, the ribbon of blood running downhill, veining the asphalt.

All these years later, Black body and white soul are still so painfully intertwined.

It is not lost on me now how the man’s name—Ell Persons—contains within it the magic convergence of language. In the biblical Hebrew, el is one of the names ascribed to God, the divine mystery. And in modern English, person is the name we ascribe to our individual human being, the mystery of ourselves, body woven with soul. Unbeknownst to them, what the mob saw in the fire is a reflection of the burning face of God in human flesh. It sees it by not seeing it.

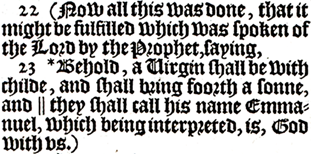

Alluding to the Hebrew prophet Isaiah, the Gospel according to Matthew will write of the birth of the Christ child:

Emmanuel. Ell Persons. (Which being interpreted is, God with us.) A mirror of the burning face of God in human flesh.

Or perhaps what the mob saw in the shimmers of heat radiating the air from the blaze were their self-made idols mirrored back at them, refracted in their own contorted faces, all the idols, each one manufactured by its bigotry feeding upon itself.

In the next chapter of the Gospel according to Matthew, the bloated, bronze-crowned king Herod, for the sake of his own narcissism mixed with paranoia, will massacre every child under two in the town of Bethlehem. But by then, the child will have escaped to Egypt, to return after Herod dies to a town called Nazareth.

Thirty years later, Herod’s son, now king, will unknowingly help finish his father’s business, one more flayed body strung up on a beam of wood, another mother weeping for her lost son.

*

One summer when I was in high school, the 1990s, I accompanied my father on an overnight business trip to Memphis. It was around the same time that I, a naïve suburban white kid, had discovered the Blues, the concealed splendor of the roots of the music that was beginning to define my youth. While my classmates were headbanging to Guns N’ Roses, I was reading the liner notes to the cassette box set of The Complete Recordings of Robert Johnson. I had been drawn irresistibly to the guitar-driven riffs that inspired rock n roll, but I was also smitten with the folk mythology of it. Everything happened at the crossroads, where it was alleged that Robert Johnson made a deal with the devil to play the guitar like nobody before or since.

Everything happens on U.S. Highway 61, the river road from New Orleans through Memphis to St. Louis to end in St. Paul, Minnesota. The mythology runs so deep that the Minnesota-born Robert Allen Zimmerman, after renaming himself Bob Dylan, would hear the burning voice of God bidding Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac on its sacred pavement.

Where do you want this killin’ done?

Out on Highway 61.

I had begun to admire my mother’s cousin Steve, who had been playing harmonica in Blues bands for years. When I told him I wanted to learn to play, he made me a mixtape of Little Walter sides.

Initially playing for the Chicago Blues legend Muddy Waters, Little Walter revolutionized Blues harp playing by cupping his hands around a microphone pressed up against his harmonica, then plugging it into an amplifier like you would a guitar. Long before Jimi Hendrix, Little Walter discovered distortion, playing riffs and solos the way John Coltrane played jazz on the saxophone.

First lesson: Muddy Waters’ classic stop-time, five-note riff: ba–de–da–DEE–duh.

After a couple months, I had the riff down cold. The trick to playing the Blues on harmonica is to learn to bend the notes. It is easier on the inhale than the exhale. You pucker your lips a little tighter and draw the air down with your tongue into your lower jaw. When you get the flow right, the reed bends to a sound between the notes on the scale, allowing you to slide the riff to make it swing: ba–de–da–DEEahh–duh.

But now I’m a man

I’m way past twenty-one

Muddy Waters sung his standard “Mannish Boy” in answer to Bo Diddley’s “I’m a Man,” which was itself an answer to Waters’ “Hootchie Cootchie Man.” Each song was built upon the same five-note riff. Each song pronounced a statement of potent personhood (I am—just what I am…) in the face of an idolatry that would otherwise annihilate their humanity with gasoline and fire.

I’m a man

I’m a rollin’ stone

I went to Memphis with my dad in search of what became of the Blues. I had little interest in Graceland, which we didn’t have time for anyway. I wanted to go to Beale Street. By the 1990s, Beale Street had been capitalized. It was a tourist attraction. That night we ate dinner at B.B. King’s Blues Club with the giant neon sign, and I hoped to see the man himself, B.B. King, the last living legend of the Blues. I hoped in vain.

We walked the whole strip, my dad and me, a strip that would be made more famous a year later when Tom Cruise did backflips down the sidewalk in the movie adaptation of John Grisham’s novel The Firm. I bought a black t-shirt with a full-length silkscreen of Little Walter playing his amped-up harp. I still have it, the image faded, buried somewhere in my closet.

Had I known then what I know now, I might have searched the sidewalk for a trace of Ell Persons’ blood, any thin ribbon faded to maroon. But it was night, and all I remember were the street musicians playing their instruments, their upturned fedoras on the dusky concrete filled with dollar bills.

I guess this is how mythology intertwines with the facts, burns the edges of our own personal histories. My parents grew up in two little towns in southeastern Missouri, five miles off Highway 61. They drove its blacktop a thousand times after they migrated to Saint Louis, before President Jimmy Carter finished Interstate 55. Fifty years earlier, thousands of daughters and sons of former slaves drove the same highway north to find better work and escape Jim Crow. A few of them played the Delta Blues in juke joints along the way until Muddy Waters got to Chicago and plugged in his guitar. Elvis Presley would spin the record on his turntable and everything would change.

When I graduated high school, my mother’s cousin gave me an amplifier like Little Walter’s, but I gradually gave up the harmonica during college. My sophomore year, when my grandfather—his uncle—died, we tried to play “Amazing Grace” together at the graveside. But I lost the melody a few bars in, and he had to carry the tune the rest of the way. A few months after New York City’s Twin Towers collapsed, at the reception after Jenny and I were married, my mother’s cousin plugged in his harmonica and played Al Green’s “Love and Happiness” with so much Memphis soul we danced the delirious night away.

It would take another thirteen years to know now what we didn’t know then, the ribbon of a teenager’s blood veining an asphalt street in a suburb called Ferguson, not far from Highway 61.

Travis Scholl’s essays and poems have recently appeared in Fourth Genre, Essay Daily, After the Art, and Saint Katherine Review. He holds a PhD in English and creative writing from the University of Missouri, Columbia, an MDiv from Yale Divinity School, and lives, works, and teaches in St. Louis. This is the title essay from his current work-in-progress. For more, visit travisscholl.com.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE