Simulacrum of Imagerie

I seem to be one of those transplanted trees, unhealthy in a new country, but who will die if they return to the native land.

Miguel Torga, Diary 1

March 5th, 1934

Lo que importa es la no-ilusión. La mañana nace.

—Frida Kahlo, Diaries

The sky is so blue outside, but here inside, unrest.

Outside: almost November, spring breezes whisking away the last bad ghosts of winter, smell of flowers in remote gardens, smell of the first ripe mangoes, strawberries misplaced amidst the carbon monoxide from cars jamming the streets. Inside: the unmoving line, a broken air conditioner, plump ladies running over people through narrow aisles without saying sorry, their overflowing carts as deadly as war tanks, cybernetic kids screaming for intergalactic toys, slow, rude, scary cashiers. And the sweat, nausea, and affliction of all the supermarkets in the world on Saturday mornings.

She looked at her own purchases. Crackers, sparkling water, brown rice and, in an outburst of indulgence, a jar of Argentinian peach jam. “Duraznos,”she repeated, fascinated. She liked the sounds of words. And couldn’t even count on her free hands to fan herself. The woman with an overstretched face crammed the counter with her provisions, two carts brimming with cholesterol and sugar blues. She sighed. She looked up, from where a CCTV camera spied on her, as if she was a potential thief. Trapped between gondolas in that gangway corridor, she also looked at the shelves on both sides, seeing mountains of plastic bags of green, pink, and yellow gummy bears, crackers flavored with bacon, onion, ham, cheese. And cans, piles of cans.

She sighed again, she used to sigh a lot, and looked outside one more time, beyond all those heads in front of her. The blue sky remained so fair and rare in that hateful city. Here inside, all she could do was remove one foot off her Havaiana – it was Saturday, “screw you”, that’s how she really felt – to place her toes, with very short and unpainted nails, over the other foot. There she was, like an egret perched amidst the sugary swamp. Her ample Indian skirt down to the ankles, patterned with many colors, the loose sleeveless blouse of white silk, the exact amount of money hidden in a pocket over her left breast. She lifted and rotated her swollen foot in the air to activate circulation. What if someone spotted her like that, not seeing her swollen foot invisible under the ample skirt? They’d call her one-legged girl, poor girl, all disheveled, wearing wrinkled hippie clothes, and above all, with only one leg. One-legged, equilibrist, not leaning on anything or anyone, no crutches, nor a cane. “Screw you,” she repeated, looking around, confrontational. But “screw you” was not enough for that mob. So, she growled: “Fuck you!” in a lower voice, but with enough hatred, exclamation point, capital letters and all. Then, she felt better, despite being exhausted, shameless and detoxed, the egret-girl.

That’s when she saw him standing in the line beside her, already passing through the cashier. He hadn’t put on weight, at least not on his face, and he wasn’t any balder. Although his skinny frame now carried a strange, artificial-looking belly. Sweaty circles under his armpits stained the synthetic fabric of his button-down, long-sleeved white shirt. Clumsily, not seeing her, he tried to shove his shopping items into plastic bags. Curious, tilting her head, she investigated them: vodka, whisky, Campari, piles of artificial savory snacks, mayonnaise, margarine, raw bloody sausages wrapped in newspaper, and another cart filled to the brim with beer cans, cheese, pâté – could it be a party? – more cans, many cans, mixed vegetables, tomato paste, tuna. The bags were tearing open, cans spilled onto the floor as he bowed, trying to pick them up, while still attempting to sign a check to pay, and nobody helped him. He was a man she knew a long time ago, when he was not yet this urbanite in a supermarket, but still a barely young man, recently arrived from years of political exile in Chile and Algeria. After that, a master’s degree in Paris in a subject she didn’t recall. She only knew he talked all the time of a certain simulacrum of a certain imagerie, sitting cross-legged on her lilac-and-mauve flowery cotton sofa, strongly tightening his legs to protect his balls, as if she was always on the verge of violating him the next second, talking and talking non-stop about Lacan and Althusser and Derrida and Baudrillard, mostly Jean Baudrillard, while she busied herself serving more chilled white wine with pistachios, contemplating the centerpiece of yellow roses, and taking heart in admiring him like that, so young, such a foreigner in his own country, terrorized with any possibility of touch from another human being on his sad, loveless, pale, coming-from-exile skin.

“You know how to live,” he used to say. She used to smile, unassuming, more sarcastic than flattered. He barely knew how much she toiled like a slave, in between her German translations, wiping walls with alcohol, vacuuming carpets, gathering curtains for the laundry, changing sheets every single day, washing dishes by hand, her reddened hands. She looked at her hands with melancholy when he said those things, while she stood by the sink lathering mostly white and silk clothes, because she didn’t, and probably she’d never, own a washing machine. Chopping carrots, radishes, and beets for raw salads, stirring in clay pots with a wooden spoon, she hated the microwave, forever and ever exhausted from it all. Her only comfort was the Astrud Gilberto and Chet Baker tape, those placid songs always in the background.

Clean, neat, hard worker, every day she was that kind of woman. Dead from exhaustion and from love without hope for that man who didn’t, and who’d never, see her as she really was, who’d never touch her either. He admired her, so he didn’t need to touch her. He granted her a superiority she didn’t own, so he didn’t have to kiss her. Disingenuous, songamonga, he collected names, telephone numbers, addresses of people and places probably useful someday for the Arduous Task of Being Successful, vampirizing each one of her friends, especially those who held some kind of power, editors, politicians, journalists, art gallery owners, movie directors, guarantors, producers. Seductive, insidious, irresistible – “Let’s have dinner sometime,” he insinuated, ambiguous, to everyone. For three years. He never gave her an orgasm. He never laid down naked by her side in bed, she also naked. At most, he would whisper sweet words like “Stay here, please stand against the glass window, the evening light is on your hair and I want to keep this image of you so beautiful, forever in my memory.”

No, she was not a fool. But, as a person who doesn’t give up on angels, fairies, baby-carrying storks, Greek islands, and Cinderella-like happy endings, she wanted to believe it. Until the sudden night when she couldn’t anymore, then threw glasses of whiskey at his face. And for days, called him late at night, drunk, leaving terrible messages in his answering machine threatening suicide, murder, lawsuits, and calling him a thief.

“I want – because I want! – my Astrud and Chet Baker tapes back, you bastard limp dick faggot,” she was so rough and irrational, repeating what her therapist had said, himself also exhausted of all of that, not specifically about him, but about all men in the world: A homosexual in the closet, who hasn’t given his ass until he’s thirty-five is bound to become a jerk, my dear. He was thirty-seven when they met. How old is he now? About forty-three or forty-four, and he was a Libra, of that kind who doesn’t know the exact time of his birth. And that disgusting belly, that Air of a Successful Person, the synthetic shirt, the sweat circles, those designer pleated pants, the cheap grocery plastic bags, three or four in each hand as he leaves the supermarket, almost fat, with a crooked back.

In the line, someone pushed her from behind with a cart. The cashier was waiting with a bored face and a provincial accent:

“Check, card, or cash, daaaaaarling?”

“Cash,” she said, throwing over the counter the twisted banknote as if it was a live serpent. Then, she picked up her few purchases and left. Ausgang!

Outside, the wind blew over her long skirt, sending it on a flight. “I’m not wearing panties,” she remembered. She thought about Carmen Miranda. Then let the skirt fly and fly. She took a deep breath. Strawberries, ripe mangoes, carbon monoxide, pollen, jasmines on suburban porches. The wind blew her red hair over her face. She shook her head to brush it away and walked slowly, in search of a street with no cars, a street lined with trees, a quiet street where she could walk alone and in no hurry all the way home. Not thinking of anything, with no bitterness, not even a vague nostalgia, rejection, resentment, or melancholy. Nothing inside and out beyond that almost-November, that Saturday, that breeze, that blue sky – a non-pain, after all.

Translator’s Note:

Caio Fernando Abreu’s writing has long captivated readers with its sharp and sophisticated language, inviting them into a world that is both deeply personal and universally relatable. My admiration for his work began in the 1990s while I was still living in Brazil, where I eagerly read his books and his weekly column in the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo. Years later, while living in the United States as a writer and literary translation student, I found myself drawn back to his stories. My reader’s perspective gained another deep layer when I started to understand his work from a translator’s standpoint and finally decided to embark on translating the stories from Estranhos Estrangeiros (Strange Foreigners). This posthumous collection had yet to reach Anglophone audiences. My appreciation for his meticulous word choices and narrative rhythm only grew. The sophisticated prose with its long, vibrant sentences, precise punctuation, and words that carry a specific meaning in Portuguese, presented exciting challenges to me.

One of the most compelling pieces I chose to translate from this collection is “Simulacrum of Imagerie,” which Abreu was working on before his untimely death from complications of HIV in 1996. This story stands out not only for its intricate exploration of foreignness and displacement but also for its relevance to contemporary discussions of identity, issues that are deeply present in my own work as a fiction writer. The title itself evokes Jean Baudrillard’s theory from Simulacra and Simulation, adding an intriguing layer about artificiality that resonates even more profoundly nowadays in our current world of false realities, the cult of celebrity, and social media.

Despite the relatable and universal themes, some aspects of Abreu’s text are deeply rooted in our native Brazilian Portuguese and became interesting challenges to translate. Punctuation, for example, was a big task I faced while working on this story. I wanted to preserve Abreu’s long, flowing paragraphs separated by commas, which are crucial for the narrative’s distinctive rhythm and voice in the original. In English, this approach is less common; the sentences can become confusing and finding a way to retain that musicality requires extensive experimentation. By analyzing the choice of words and their sounds in both languages, I was able to preserve the cadence of his prose. For instance, I carefully deliberated over phrases and sought synonyms that would echo the rhythm of the original. Ultimately, my commitment to honoring the poem-like quality of Abreu’s work guided many of my translation decisions. For example, when translating “Continuava o céu azul tão claro e raro naquela cidade odiosa,” I opted for “the blue sky remained so fair and rare in that hateful city.” This choice – instead of a more accurate synonym for claro (clear) – preserved the sonorous qualities of the original Portuguese, ensuring that the beauty of Abreu’s language was not lost.

Another significant aspect of my translation process involved the decision to retain certain foreign words. For example, the word “songamonga” (a Brazilian slang for a person who’s sly but pretends to be naïve) and “durazno” (peach in Spanish) were kept in the original language. The same applies to “Ausgang,” a German word meaning “exit” and used by the main character, a German translator, and “imagerie” in French, the original title’s word that conveys a particular sound, but also connects to Jean Baudrillard’s native French. I believe some foreign words enrich the narrative, bring out the voice, and contribute to the theme of cultural estrangement.

Conversely, translating words like “perneta” (one-legged girl in the English version) posed a challenge due to its slang connotation, which can be perceived as both lighthearted and potentially offensive. Equivalent words in English, such as stumpy, were much ruder and considered more offensive compared to the term in Portuguese. The right balance in tone while conveying a similar sentiment in English, required a thoughtful choice of idiom. I chose to use ‘one-legged,’ which doesn’t carry the same playful tone as it does in the original, but is not as strong as ‘stumpy’ or as clinical as ‘amputee.’ The satirical tone of the paragraph was carefully preserved to convey the sentiment that’s missing in the translated word.

As I reflect on the entire experience, it becomes clear that translating Caio Fernando Abreu was not only an immense privilege but has also deepened my appreciation for his literary genius. Each line invites readers to explore meanings on multiple levels, and through this most profound engagement, I have come to love his work even more. Connecting the threads of his narratives, I recognize the lasting impact of his voice and the universal themes that resonate across time, language, and culture.

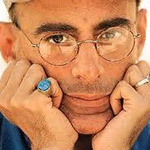

Caio Fernando Abreu (1948-1996) is a Brazilian writer who continues to find new audiences around the world. He is one of the most influential writers of his generation, one of the first to speak candidly about drugs, AIDS, and homosexuality, and a sharp chronicler of urban Brazilian life between the 1960s and 1990s. Born in Porto Alegre, in the deep South of Brazil, Abreu lived in São Paulo for many years. Abreu wrote novels, short stories, and plays, and translated Susan Sontag, Sun Tzu, and Carson McCullers into Portuguese. He received critical literary prizes in Brazil, such as the Jabuti and APCA. He has been the subject of numerous literary theses, and some of his books and stories have also been translated into French, German, and other languages. At the time of his death, he was a celebrated columnist for the daily newspaper O Estado de São Paulo. Some of Abreu’s short stories have also been published in English, including “Sergeant Garcia,” “Beauty, a Terrible Story,” “Shit About Love,” and “Beyond the Point.” Photo by Adriana Franciosi.

Ines Rodrigues is a Brazilian writer, journalist, and translator in New York, and the author of the novel, Days of Bossa Nova. She holds an MFA in Fiction Writing from Columbia University and completed the Literary Translation at Columbia (LTAC) coursework. Her short fiction has appeared in The Plentitudes Journal, Tint Journal, and the Writers Read Anthology. She received a Word-for-Word translation grant from Columbia University in 2023. She translates from Portuguese and Italian into English. inesrodriguesauthor.com. Photo by Kristina Rathod.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE