Oft

Why does it recur to me ever oftener

One Evenfall Dell, its Brook and Firs?

One Star peers fathomably lower

And dawns on me: from thence in silence I transfer.

Then I am drawn far from good Mortals.

What could embitter me solely so?

The Bells catch on to their tolls,

And starts the Star to glissando.

Oft

Warum erscheint mir immer wieder

Ein Abendtal, sein Bach und Tannen?

Es blickt ein Stern verständlich nieder

Und sagt mir: wandle still von dannen.

Dann zieh ich fort von guten Leuten.

Was konnte mich nur so verbittern?

Die Glocken fangen an zu läuten,

Und der Stern beginnt zu zittern.

Evening Bound

Will no lovelier Bird sing?

Each Scrub remains voiceless.

Only an Imago with flowerful Wings

Revels round the Field of abounding Ryegrass.

Sunflowers kneel back down to Earth.

Tanned Shadows cling to the nigh Wall:

Grave, sweat-soaked Horses pull forth,

Through the lowering Land, high Hauls.

Gegen Abend

Will kein lieber Vogel singen?

Alle Büsche bleiben stumm.

Nur ein Falter mit beblümten Schwingen

Tummelt sich im Roggenfeld herum.

Sonnenblumen neigen sich zur Erde.

Braune Schatten haschen nach der Wand:

Schweißbesickert ziehen schwere Pferde

Hohe Fuhren durchs verwolkte Land.

Translator’s Note:

Like much of Theodor Däubler’s lyric poetry, “Oft” and “Evening Bound” both distill and cavort in the mythopoetic light and shadow cast by his epic literary debut, Das Nordlicht (The Northern Lights). Däubler describes the central image of auroral light as celestial odyssey in these exuberant terms:

I was overjoyed to feel that the earth contained within it much of the sun and this solar element combined with us to fight against gravity, striving to joined once more with the sun. … There is a gleaming penetration between that sun which has been released from the bonds of earth and the divine sun itself – and this causes the polar light within the month long darkness of the poles! The earth is longing to become a radiant star again (translation by Raymond Furness from his book Zarathustra’s Children).

In “Evening Bound,” polar opposites (light and darkness, earth/chthonian and heavens/ethereality, death and revival, singularity and community) are both bound together and released, leveraged as an image of transformative flight, and perhaps as a departure from an everyday process of binary thought and identity. The Imago at the center of the poem is drawn from the German word “Falter,” which can either refer to a moth or a butterfly depending on the time of day. Those who pin down winged insects may be called Lepidopterists, though the term “Aurelian” is archaic designation for them, drawn from the fleeting golden color of the beings who emerge from an aurelia, or chrysalis. Since “Evening Bound” is set during the liminality of twilight, or the golden hour if you prefer, I landed on the word “Imago” to preserve the union of opposites I felt in Däubler’s use of ambiguity, for he could have chosen one of the more definitive terms for this image: Tagfalter or day-flyer (butterfly) and Nachfalter or night-flyer (moth). Imago also carries a psychic charge: it refers to an unconscious idealized image of some figure that holds sway over one’s actions, such as a parent, or, in Däubler’s heliocentric cosmology, our closest radiating star, the animating sun.

Along those same lines, the speaker of “Oft” appears to me in a kind of liminal orbit, recalling either an apotheosis or exile from humanity that tightens as rebounds. I found it difficult to align musical and imagistic sense in English, especially in the second and fourth lines in both stanzas. In the first stanza, rather than “Firs,” I originally preferred “Pines” for its underground resonance as yearning; though I think both words, when felled, can be traversed as bridges to solstice traditions that center eternal light. Firs has a rhyming advantage with “transfer,” which is how I translate the two-fold ambiguity of the verb “wandle” here: it compresses the action of walking with that of transforming, another resonance of departing. This tension, including my own faltering towards Däubler’s music, is what led me to hear an operatic richness in the shuddering and trembling of “zittern,” the original poem’s final word.

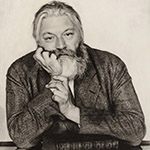

Theodor Däubler (1876-1934) is the author of more than twenty books of poetry, prose, and art criticism, including The Starchild, The Starlit Path, With Silver Sickle, Hymn to Italy, The New Standpoint, and his debut epic The Northern Lights. Däubler served as the chair of the German PEN club, was awarded the Goethe Medal, and in 1928 was nominated for Nobel prize in literature. Portrait by Hugo Erfurth.

Sean Zhuraw’s poetry and translations have appeared in Boston Review, The Hopkins Review, Tin House, The Offing, Defunct, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. He earned degrees from Columbia and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop where he won the John Logan poetry prize. He teaches English and Creative Writing at the Community College of Philadelphia. He lives gayly in West Philly with his husband and two cats. His Instagram is @toystutter.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE