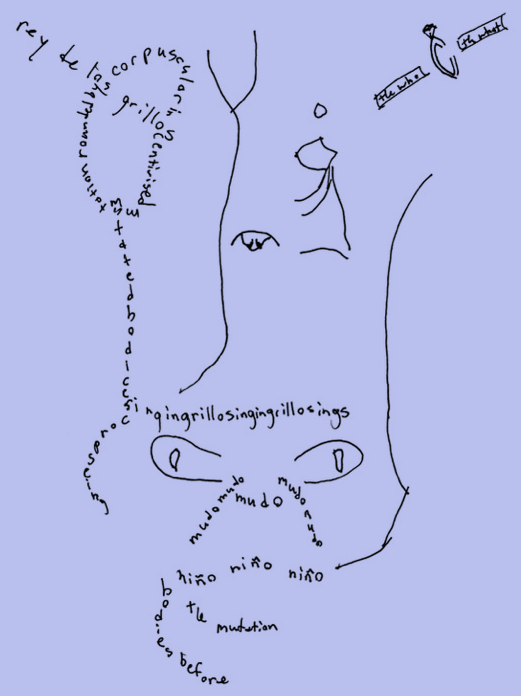

from The Lorca Book

Hid himself in letters

Stand up and become human, he said

I’m laid down in letters

He wanted an audience of sex and death

An orgy laid down in letters

He dragged danger like daggers clatter across steel sheets

His danger covered the stage in letters

Absurd, his shadow a flitting pose of blood,

He hid himself in death.

There was danger in his sheets,

Two bullets in his bu[m]hole (sic.)

For being queer, it was said.

He lay down in a letterless grave;

Buried outside of letters, his shadow flitting dangerous.

The letters just didn’t become human

His audience a thin mask of letters

Jets of blood absurd jets of confetti

Four horsemen no four men in suits

He wanted an audience of sex and death

I’m laying him in letters

When we cry for jets of blood

Instead of death in cubicles and jail cells

The IRS and the FBI

Hear me hear our shadows flitting

The letters don’t work

He broke bread like Jesus bleeding in childhood

saying his prayers listening like someone was listening

Asking for his jet of blood

Proof of living (IRS letter box)

Is he listening to me now?

Letters never work

We want real REAL lemons

THIS LEMON THAT LEMON

POETRY IS SHIT PILES OF LEMONS ON A STOOP

BASKETS OF BLOOD SOURED

WE WANT REAL SHIT

Jets of death

Solid living lemons

I can lay down with

Because you touched me

Because I am grabbable gravable buryable

This is evidence

A real body in letters

(Or maybe these letters

(Look look the letters

Are failing

(

The Silent boy

The little boy looks for his voice.

(The King of the Crickets had it.)

In a droplet of water,

The little boy looked for his voice.

I don’t want it for speaking.

With her, I will myself make a ring

That will carry my silence

On your tiny little finger.

Far away, the voice is caught

Putting on a cricket’s garb.

first and mutely

mute sing spring

of grasshoppers’ bodies

first before the mutation

loud bodies corpseing

before the first corporeal

mutation

corpse of grasshoppers sing

The corpus

body of mutated boys

sings first

grasshoppers’ king

bodice

The mute boy’s

primavera

first

mutated

bodice

primera

mudo

corpus

Before

the first corporeal mutation,

the body of loud bodies sings:

first king of grasshoppers’ bodies,

loud corpus of grasshoppers sing.

Mutely, boys before the first corpus,

the body of grasshoppers sing.

Mutation before the first king,

the corpse of grasshoppers sing.

Before mutation, the body feeds mutely

the grasshopper wings,

so he may sing

through the corpus of

grasshopper kings

before the first mutation

the body feeds the boy

the mute bodice, king

first boy sing

(the king of crickets had it)

el primer hombre

la pintura de las alas

comiendo el muchacho

cuerpo en cuerpo,

rey en el rey

Translator’s Note:

I’ve been translating Lorca’s work for over 10 years, and I have recently begun an experimental project channeling the poet himself. Channeling is a form of translation, and over the course of becoming a “Lorca translator,” which I call myself rather than a “Spanish translator,” I’ve come to think of these praxes as the same. In translation and in channeling, I am listening. Lorca is a queer ancestor, and so I try to listen to his work and divine my own place in relation to it, which means placing myself and my text. Just as with translation, using channeling results in mistakes and misreadings which, I think, can be strong interpretations all the same.

My project of mistranslating Lorca by channeling is under the working title “The Lorca Book” in homage to Robert Duncan’s H.D. Book. Both are in direct communication with forebears who share formal praxes and identities with the author-medium. Through ritual and invocation, Lorca became a sounding board and a mask for my author self, and throughout the book, we converse in the margins—which I think is what any translation is formed from, whether the translator chooses to hide the conversation or not.

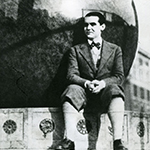

Federico García Lorca (1898–1936) was a Spanish poet and playwright who, in a career that spanned just 19 years, engaged and revitalized Spanish poetry and theatre by fusing tradition with modernism. Lorca’s most well-known works include the poetry collection Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York) and the “rural dramas”* Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding), Yerma (Barrens), and La casa de Bernarda Alba (Bernarda Alba and her House). He was executed by a Spanish nationalist firing squad in the first months of the Spanish Civil War. Photo: Federico García Lorca at Columbia University, 1929. Courtesy of the Fundación Federico García Lorca.

*English titles are translated by Shoemaker.

Robert Eric Shoemaker is a poet and interdisciplinary artist. Eric is the author of Ca’Venezia(2021, Partial Press), We Knew No Mortality(2018, Acta Publications), and 30 Days Dry(2015, Thought Collection Publishing). His poetry, translations, and essays have been published in Rattle, Jacket2, Signs and Society, Asymptote, Entropy, Gender Forum, Exchanges, and others. Eric earned a PhD from the University of Louisville and an MFA from Naropa University. He is the digital archive editor at the Poetry Foundation. Photo by Sally Blood.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE