We Are Not What Divides Us

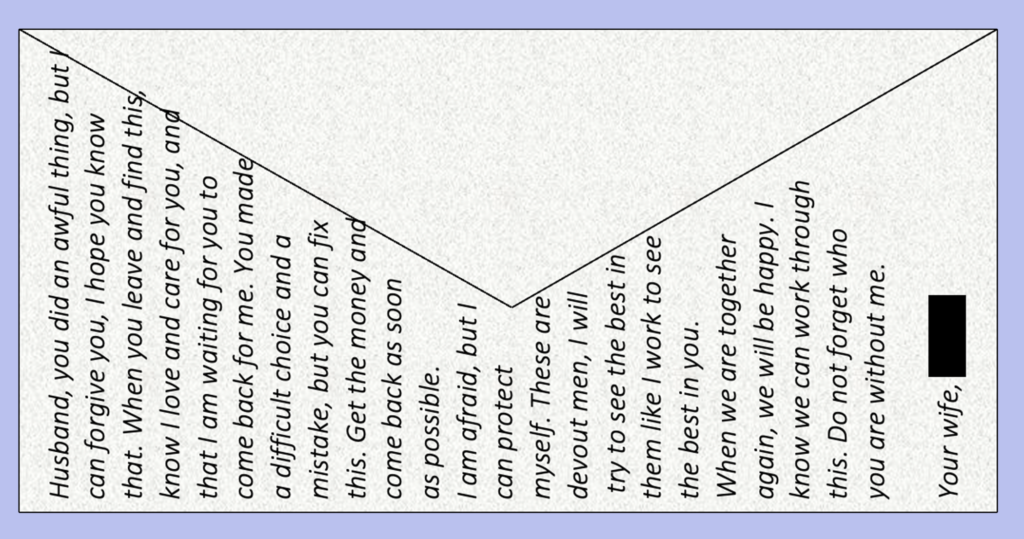

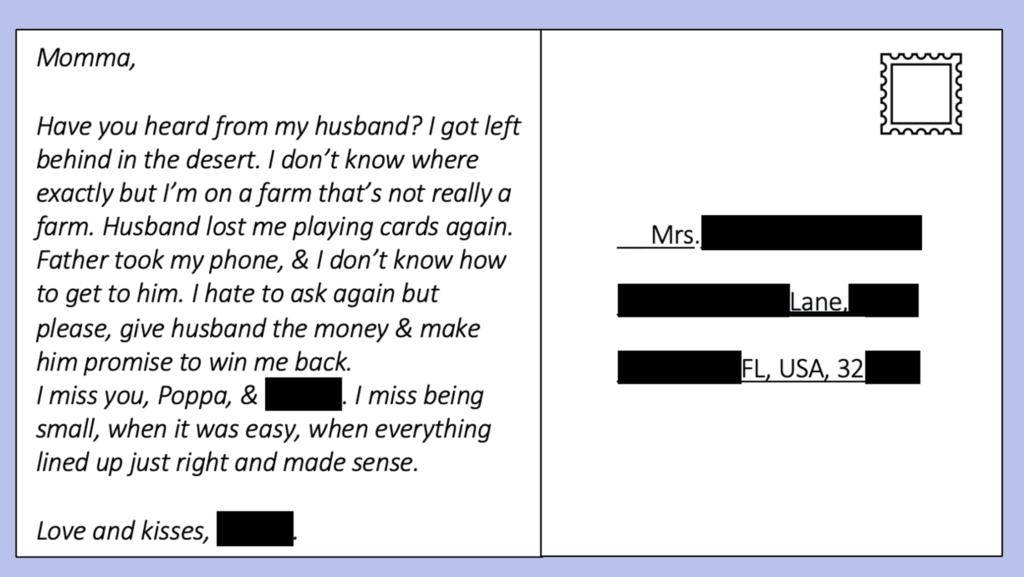

In the van at night, I watch my husband play poker on his phone beneath the blanket. I watch like most women watch, silent and allowing, unwilling to enter another fight as if we weren’t in the desert in a discount van to leave his desire for luck and chance behind. We’d told our families that we sold our two-bedroom, with enough land for future children to grow, so we could travel before settling down. How delightful it was, my husband had said, to shed our earthly burdens. He’d bet everything, even my retirement, on the cards that never turned up in his favor. I close my eyes and wait for the desert to cleanse us both.

In a gas station, we learn of the Father. A leader of a community of devout men, devout to the earth and its harvest more than to a higher power. My husband would never pass on the opportunity to meet such a fruitful man, so we get directions scrawled on a napkin that I interpret even in the dark. I am happy to visit a commune, to stay at a place without cell service and to meet someone who can help my husband find our purpose.

When we arrive, the Father opens the front door to his home and gladly welcomes us in. A black hole of dread opens in my stomach when, in the front room, I see an ancient beige desktop monitor set up on a betting screen. No matter where we drive, it seems, we always end up closer to trouble than further away.

After introductions, my husband sits down with Father eagerly to play. Father is a silent figure, dressed in a white smock dotted with dirt or some other earth-stain. I’ve never seen a man look like he’d be more at home on a stage, his gestures too wide and his voice too big, hesitating after speaking like he is waiting for applause or a laugh or a groan, which I, in my discomfort, oblige.

I chew my fingernails as my husband wagers what little we have left: pocket change, his wedding ring, a traveler’s check from my mother I’d hid underneath the passenger seat of the van. He comes close to winning each time, and I feel the odds almost turning in our favor, but Father always, humbly, comes out on top, clicking to flip over his better hand.

It is drawing close to midnight when my husband’s shoulders sink pitifully and he says, “Father, I’m all out of money. I have nothing more to lose.”

Father shifts in his seat, the wooden legs creaking on the floor. “A man with such a beautiful wife is still a very rich man,” he says.

My husband kisses me on both eyelids and then bets me on his hand. He clicks and clicks and I watch and listen to the fake sounds of a casino tinkling through the speakers. It’s dry and warm as an oven in the front room but when he loses me, I go cold and wet all over.

The Father leans back in his chair, crosses his ankle over his knee so I can see the bottom of his foot, calloused but surprisingly clean. He tells my husband he can stay for the night but will leave me behind in the morning.

“I lost my love, my lovely,” my husband says, kneeling to hug me around the waist.

“You can’t have loved her so much if you wagered her like pocket change,” Father says. Husband weeps into my stomach, I hold his head and stare at our three clear figures reflected in the large windows. I feel only a sorrow so expected and heavy I want to lie on the ground and be buried beneath its weight.

*

*

In the morning, I wake to my husband tying his shoes, propped up close to my face on the mattress. I watch his thin fingers fumble with the knot. When I ask him to promise that he will return for me, he kisses my forehead and leaves through the door.

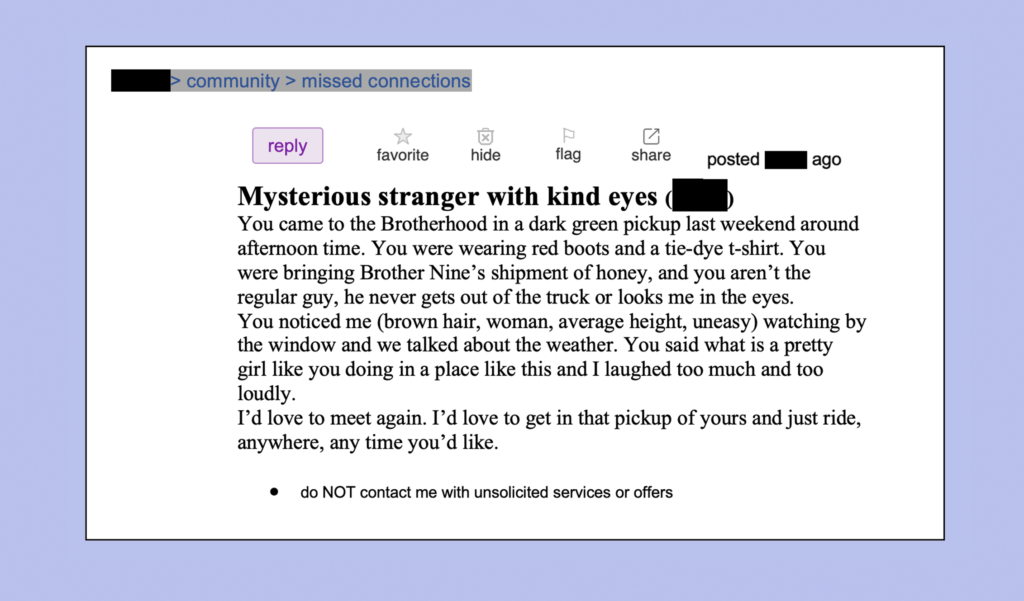

I stand behind Father and watch as my husband climbs into my van, our van, the van I bought off Craigslist when I decided I wanted to travel, to get away from my home and my life before my husband pleaded that I take him too, that we could find our love again on the road. I believed him because I wanted to be loved, so I got out of the van and handed him the keys that he now starts the engine with while I look on over Father’s shoulder.

Father holds up his hand in one solemn wave, but I can’t see my husband’s face in the glass, and I don’t know if he’s looking at me, if he’s crying or stoic, if he knows he has made a mistake. The tires churn up rocks that skitter across the path as he pulls away. I remember the feeling of driving the van home for the first time, the way it shuddered on the highway and I was jittery with adventure and then desperately trapped by my own fear, the huge unknowing that stretched before me like rows of shark teeth. I was so aware of my fleshiness and all of the ways I could get hurt going it alone. I hope my husband feels that too now, the danger of freedom, of being just one body adrift in space. I hope this fear will bring him back to me.

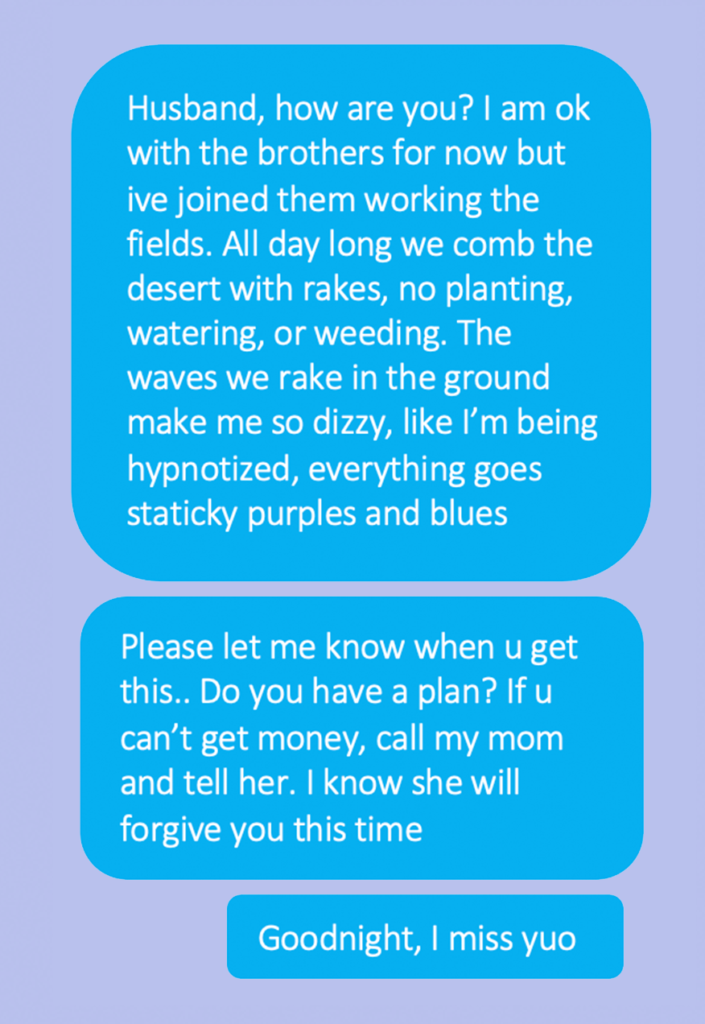

I meet the Brothers later, after I am shown the kitchen in Father’s home and how to cook his favorite breakfast: oats, thick with goat milk on the stove. After I’ve cleaned up, I follow Father out to the fields behind the house. He calls them fields, but they’re not quite fields as I know them—I’ve driven through stretches of wheat, shifting like dancers in the wind, so careless I wanted to pull over, lie down, and wrap myself up in rustling. These fields are bare-cracked desert that flake up in fine clouds when I stamp over it in my sandals, and I wonder how they could prophesize anything will grow.

Men sprout slowly into view, dotted across the desert in denim pants and jackets, deep blue faded to a near-white. It’s so warm that the blood in my hands pool by my sides and I can feel my wedding band, department-store silver, tighten around my skin.

Father removes his hands from their tuck in his sleeves and gestures towards the men who take off their hats in welcome. “This is our livelihood,” he says, so solemnly that a shiver tickles the underside of my biceps, the weight of this mission holy as a church. But I don’t see anything living, beyond the men, for miles.

I shade my eyes from the sun, my moist forehead sticking to the curve of my hand. “Father,” I say, “What livelihood? I don’t see.”

A man, who Father introduces as Brother Seven, approaches me with a long-handled rake. “Don’t worry, Mother. Father teaches us all how to see.”

I take the rake in my hand and little splinters prickle my palm. My chest tightens with the way he calls me mother. It feels heavy in a different way, like the prayers I’ve whispered into my knuckles on a walk home alone late at night. Father pats me on the shoulder. I emit radio waves, extend out across the plains, around the earth and up and out into the universe. I imagine how they’ll never stop traveling, they’ll only grow weaker with distance and time. “Go now, my child,” Father says, “Brother Seven will teach you the way.”

*

*

While we work the fields, Father sits on a lifeguard tower above the desert. It’s a classic tower, white and wooden, paint whipped and chipped from the beating sun and storms. He holds a rusting umbrella in his right hand and binoculars in his left, and he watches us as we rake back and forth. I wonder, with him being so far above, if he can see something we can’t, if we’re making our own little messages for someone much bigger and higher to read.

I rake quick lines like I’ve been told, but by the time I’ve reached the end, the wind has smoothed my effort, like I’d done nothing at all. When I grow frustrated, Brother Eleven smiles so knowingly I want to crush a small animal between my hands. He tells me that it happens to us all. I watch his metal rake grind, twinge, and bump off rocks and other small things hidden beneath the surface. I think this work will never be done.

It’s only been a few weeks, so I try not to worry, I need to have faith that my husband will return for me. He’s never lost me on a game but he has left me behind at a table as an IOU. He hasn’t left me this long, but it’s different now. I was the last valuable thing he had to lose, and I imagine him, sweating at a poker table, waiting for luck. This faith keeps me from collapsing in despair underneath Father’s gaze.

I run backwards with my rake to catch up with Brother Eleven. He’s the youngest Brother, with a soft, freckled face and a preference for overalls, the jean still dark blue and endearing. My rake snags a rock and jolts up, twisting the muscles in my wrist. In the tower, Father blows his whistle. I slow down.

I ask Brother Eleven why he joined the Brotherhood.

“Same as you,” he says. His breath comes fast and quick, whistling somewhere in his throat but he smiles calmly, like they all do, like I’m a younger, simpler sibling.

“On a bet? Is that why Father keeps a PC in the doorway?” I ask.

“No, Mother Three,” he says gently. “I mean it was destiny, same as you. It doesn’t matter how we got here. Only that we’re all here together now.” His face is round and warm with the work.

“I understand, Brother, but where are you from? What is your family like?” I ask. I want to know what he dreamed of being when he grew up, his favorite color, his real name. I want to know all the little pieces that make him up.

We reach the end of the plot. Brother Eleven turns and starts back down the row, but I stop to catch my breath. Over the grinding of his rake, Brother Eleven shouts, “We are not what divides us.” His powerful knees pump out at the sides, propelling him backward, his taut arms pulling evenly. “We are what brings us together.”

I twist the rake in the hot sand, resist the urge to bite my hand. This is our solemn prayer, an everyday anthem like the pledge of allegiance I had to say hand-over-heart every morning in class. I also do not fully understand what it means or how it binds us together. Father blows his whistle. I spit into the dirt. I turn and pull my rake through the field. Under my breath, I savor my divisions, juicy like an overripe peach: Florida, loud but loving, marine biologist, forest green, Rowan.

*

*

In the pit, I lie on my back and shield my eyes from the sun. I miss the trees more and more each day, real trees, not the bent and gnarled Joshuas that mark these fields like crucifixes. I miss the lime-green wide stretching canopies that knit together to shield whole ecosystems from the sun. In the pit, I can feel the earth on my bare arms and calves. Whenever I dig deep, I find a coolness I crave and can’t always understand that the earth has a core, that somewhere deeper inside it’s bright and hot like the sun. The earth too has a heart.

The Brothers stand above me in a ring and pray. I can barely tell them apart because of the brightness, their shifting jean-blue shapes, and only Father in his white smock and glinting glasses stands out. Father was the one who told me I would be baptized today, a celebration and acceptance into the Brotherhood, a formal relinquishing of my sinful divisions. I told him I had already been baptized, I was a good Catholic girl, but he shook his head and smiled the all-knowing smile that told me I didn’t understand, and I couldn’t ask any more questions to try to. They like me best when I don’t know.

The chanting slows and the humming reverberates against the shallow walls of the pit. A slick film emerges on my skin. The sound reminds me of 14th century Gregorian chants I listened to on YouTube back in college, before I met my husband, when I still wanted to know what it felt like to be held.

Father leans over the pit, his head blocking out the sun. “I will now ask you three questions,” he says. I nod, my hair rustling in the sand. “Do you believe in the one true purpose?”

I nod.

“Will you live and serve the Brotherhood, with light and kindness in your heart?”

I nod.

“Will you turn away from sin, renounce your name, and obey the Father for the rest of your life?”

I nod and feel a drop of his sweat land against my top lip. Then, the chorus rings out, “Father, thank you for giving us Mother Three and her light for the rest of our days.”

They throw in handfuls of hot desert sand, bouncing sharp against my bare legs, arms, face, and I close my eyes and my lips tight together to keep it from working its way in. I do not believe what I agree to, but how could I say no? There is only desert for miles.

Sand works its way into my mouth, dry and a little salty, crunchy between my teeth. I wonder how long they will keep throwing it in, and how long I will be in this hole and if I will crawl out myself or if someone else will reach in. And I imagine my baptism from their perspective and can feel the sand in my fists, and for a moment I’m terrified that I’m being buried rather than coming into a new life.

*

*

I am not surprised when Father informs me of our marriage. At night I sit beside him while he gambles online. He sits in a wooden kitchen chair and I sit cross-legged on the floor, working my way through patching the Brothers’ clothes. In the first few weeks, I had to teach myself how to sew, and now I can patch all types of problems with only the tiniest little scar left behind as witness. I watch the screen as best I can for my husband’s username without poking my fingers. I imagine him, searching the infinite lobbies, playing and betting and folding until he finds the Father. Until he can play and prove how good and loyal he is, and then I can go back home. But I know this is a fantasy; I have no loyal husband or two-bedroom home.

The needle slips into my thumb and I hiss air out of my two front teeth. Father turns to look down at me, pressing his palm into my scalp. I suck the blood on my finger. “My child, we will be wed. And then you truly will be Mother, as the Brothers have taken to calling you.”

Mother Three is what they call me, and I’m not brave enough to ask what happened to the other mothers, and if they’re counting up or down. Sometimes I walk by my baptism pit out back in the fields behind the dormitories. They never filled in the singular pit, and it’s the size of a body. Out there alone, I swear I can feel the other mothers turning below my feet.

“But Father, I’m already married,” I say, stretching the fabric between my thumbs. “You won me from my husband, remember?”

Father shifts in his chair and looks above the clunky monitor. There is an embroidered fabric rendering of the American flag and over it, in uncertain red stitching, reads: ᗯE ᗩᖇE ᑎOT ᗯᕼᗩT ᗪIᐯIᗪEᔕ ᑌᔕ. It looks like a child’s hand, or like my own stitching when I first arrived here. I try to picture the Mother’s hands, I wonder if they’re dry like mine, dappled with scars like mine, if the same needle I now patch socks with too slipped from her control, jammed up into the tender flesh beneath her nail. Some nights I feel more like the other mothers than myself.

“What husband?” he says, “You were grown in the desert, by the brotherhood, like the rest of us. We harvested you from the field together. This is our livelihood.” He steeples his smooth fingers before his face, purses his lips so the corners of his eyes fall. I do not think he is praying. I think he is only pretending to be a man of deep thought.

I do feel grown in the brotherhood, out in those fields every day, dragging the rake back and forth over the sand. The desert is in me, I cough dust and my skin is cracked like salt flats, my bleach-blond hair growing out a reddish brown. Sometimes I wake in the night to a prickle in my hip, the underside of my foot, behind my shoulder blade, and when I touch there, I pull out cactus thorns like gray hairs.

Father returns to poker. His wanting eyes shimmer, the animated cards reflected upside-down in his glasses, distorted and hungry. I hate the desert and my Brothers, the Father and our livelihood, and the senseless repetition, playing the same games and the cards that never turn up in my favor. Father grumbles and goes all in, I poke my finger with the needle. Blood puddles up and I squeeze it out onto the fabric, glistening and cough-syrup red. One husband was enough, I think. I will never be married again.

*

Transcript of 911 call placed on Tuesday, September 21, 2017 at 14:09pm

Transcribed by James Marlboro, Dept. of Public Safety

Dispatcher: 911, what is the emergency?

Caller: Hello?

Dispatcher: This is 9-1-1. Are you in need of fire, police, or EMS?

Caller: Um, I don’t know, I didn’t know who to call.

Dispatcher: You have to speak up, ma’am. I can’t understand you. Why are you calling?

Caller: My husband lost me but he hasn’t come back. And I waited awhile but I don’t know. I don’t know if he’s coming back.

Dispatcher: (typing) Are you presently in danger?

Caller: (pause) No, not like that. But the wedding is soon and I’m in the middle of nowhere and I have no way to get out.

Dispatcher: What is your location?

Caller: With father, on the farm…I’m in the desert, and (inaudible)

Dispatcher: Ma’am you need to speak up. Can you explain to me again how this is an emergency?

Unidentified person: (unintelligible)

Caller: Uh (pause). Never mind, I have to go.

Ended by caller at 14:13pm

*

The night I leave the Brotherhood, I am afraid. I’ve watched enough true crime and lived long enough in the world as a woman to anticipate all the violent ways leaving can go. Father has been good to me, mostly, because I did what I was told—I obeyed my husband’s forfeiture, I paid his debt, and I cooked and cleaned and kissed and raked and gave up my clothes, my name, my sins. But even when I am lying beside Father in our bed, I fear that as soon as I slip off the creaking springs, he’ll sit up, knife in hand, ready to hold me down. Since my husband left, I had felt powerful in playing the good wife, stoically accepting my fate. I’m afraid of truly understanding what it will be like to be owned.

Father does not stir when I get out of bed and put my shoes on. My heart beats so quickly I tremble, bump into things, my hands unsteady enough that it takes five tries to unlatch the door. Then I’m outside, the cool night air tickling my skin like ghost hands, my neck prickling with expectation of being caught. I walk into the darkness toward where I think my husband and I entered so many weeks ago, in the opposite direction of our fields, of my Brothers. I don’t look back but I imagine the night like a black hole swallowing the ranch, the dormitories, then the fields with my baptism pit, gaping and empty, until I am alone.

In the darkness, I feel weightless like I did that time I drove the van home, when the true freeness of my life cracked open like a nut before me. I was so afraid of leaving and testing the Father I didn’t anticipate the fear of being out here in the desert alone at night, the flat vast expectation of the earth and the choices I will need to make. I feel the same terror of the endless responsibility for my body, keeping it clean and fed and alive and happy, when all I want is to stop growing in space, to crawl back somewhere quiet and safe.

The desert shifts below my feet, uncertain and slippery so my ankles ache from trying to keep stable. Only my husband ever made me shrink down, I fit nicely into his comforting palms. I want him again, I want to know with a yearning so deep if he tried to reach me like I tried to reach him. I want to know that he has never felt so empty, that he hasn’t found something better to fill his palms. I want him to stumble upon me in the dark and guide me home by the hand.

My foot catches on a rock, sending a vibrant wave of pain through my knee but I don’t fall, I keep walking forward. It will be dark for many more hours but I hope when the sun rises I will have caught up with that shifting horizon, and I’ll peer down and see a whole city, wide and shining before me. But for now there is only darkness, the howl of night creatures, and the feeling of growing, the electric fear of my body stretching too far.

*

A message caught between radio stations while driving through the desert at night —

Mialise Carney is a writer and MFA candidate at California State University, Fresno. She is the senior fiction editor at The Normal School and her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in swamp pink, Booth, and Barren Magazine. Read more of her work at mialisecarney.com.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE