The Silence of Chagos, an excerpt

Mauritius, 1973

In the sentry box at the port’s entrance gate six photos are glued to the wall at eye-level, next to Tony’s chair, from which he monitors the comings and goings of port officials and employees. Six. One for each of his angel’s birthdays. Sometimes he tells himself that he could have had others. He could have made a tapestry of their faces, to cover that too-grey wall. His wife miscarried a year after the birth of their little prince, and the doctor made it very clear: there would be no more children. But he was so happy with his little boy, his gift from the heavens; he loved to repeat those words. And his little laughing face filled his box with more than enough light, anyway.

The other day, she told him that her little man was prettier than a serin bird, but that he was beginning to show some cheek. It’s true that she’s watched him be born and grow. Seven years flew past since Tony first saw her, at the farthest edge of the quay, scrutinizing the sea as if she wanted to cleave it in two, and she is still there. She always returns, though at irregular intervals. The groove at the corner of her mouth has deepened. The worn cloth of her red headscarf betrays a few strands of grey, there, at her temples. But her posture hasn’t changed. She stands like a barbed wire fence, impenetrable, with her back against the city humming behind her. She seems consumed by the sea as if poised to walk into the water, to dissolve into the blue. This is what Tony says to himself on these occasions, when his brain becomes crushed by the weight of summer’s portlouisian heat.

It was on one such day that he finally resolved to talk to her, to offer her a little water. She had stood in her customary place, motionless for so long that just looking at her made him sweat. She didn’t refuse the bottle he held out. A sort of unspoken truce seemed to settle between them. He let her enter and exit the quay, no questions asked. Sometimes he struck up a conversation with her as she passed. Nothing major. A remark on the weather. At first, she wouldn’t deign to give a response. Then, she’d aim a slight nod in his direction, a small grunt of recognition, a few short words. A yes or a no, maybe. Until the day he showed her the photos of his little gentlemen. It brought the flash of a smile to her face, or almost. She was reminded of her youngest, just two years older. She evidently possessed encyclopedic knowledge on the subject of children, and he sought her advice on bronchitis, teething, first nightmares…

In turn, she asked him about the port, its routines, details on the arrivals and departures of each ship. One day, it must have been in 1969, he couldn’t remember the precise month, she leapt at him, almost wild.

“Ki été sa bato la?”

“Ki bato?”

“Sa gro bato dan milié la rad la?”

He doubted weather she wanted to know more about that ship, which had arrived the day before. It was the MV Patris. A vessel for the middle class people that wanted to play luxury cruise. An aging liner, with dining rooms, a ballroom, separate swimming pools for adults and children. It was returning from Djibouti and making a stopover in Mauritius, to the East. A sharp gleam came into her eyes.

“Li pa al Diego sa?” She demanded.

He had laughed. Diego? No, that boat was certainly not going anyway near Diego, it wasn’t sailing up, but down, on a long journey to Australia.

“Lostrali? Ki été sa?”

She had never heard it mentioned. He explained. At least as much as he had understood. It was a new Eldorado, where a number of Mauritians, stricken with fear by the fledgling Mauritius Independence, had decided to try their luck. They preferred the sense of security that came with living in a British colony, especially when compared to the change that, for some quarters, looked more like Indianization than freedom. The MV Patris was transporting members of the creole bourgeoisie who’d rather sell all of their possessions and leave their country than be forced to use rupees. A voyage to Australia, to avoid becoming Aboriginals in the land of the dodo.

Tony repeated a phrase he’d read in a newspaper that riled against the campaign as “ridiculous and unpatriotic.” But Charlesia didn’t ask him the meaning of “Aboriginal”. In fact, it seemed she wasn’t listening to him at all, completely absorbed by the spectacle that was unfolding before her.

For three days she returned to her place on the quay, relentless in her desire to witness every last detail of what was happening at the port. On the first day, she could make out women, their sharp features contrasted by somber headscarves, and tired men dressed in overcoats, all milling about on the lower deck. They must be Greeks, Tony said to her. The next day was full of unrest. Those charged with transporting worked all through the afternoon, carrying cargo and luggage from the quay to the Patris and back again. Finally, the third day was full of good-byes. A crowd swarmed onto the quay as the first glimpses of dawn crept into the sky. From a slight distance, Charlesia watched the exchange of hugs, kisses, well-wishing, tears from some and laughter from others, as children ran in every direction at play. As they made their slow progress up the gangway, the passengers looked down at the scene they were leaving behind. Charlesia was struck by the strange mix of melancholy and forced optimism they all exuded. She stayed there, a couple yards away from the waving handkerchiefs and cries of adieu.

Other ships had come and gone again. Container ships full of an array of merchandise. She often saw Chinese fishing vessels nearly hollowed by rust, as they maneuvered alongside the port harbor. They sat there, placid, exhibiting none of the bustling urgency contained by their crews, fierce men who sauntered through the sweltering capital center, scouring the sidewalks for whores. She didn’t like these ships. She had the vague impression that they had become too accustomed to the sound of tears, echoes of beatings and the violence of bodies against bodies ricocheting against the bridge’s scrap metal; their hulls seemed bursting with it all, even the steel jumbles of their windless, sailless masts were saturated. They were glorified tubs, stinking of fish and violence.

But that didn’t keep her from returning from time to time, hoping, believing that the Mauritius or the Nordvaer would appear at last. Today, again, she is there. She heard from a docker living in the same settlement district as her that a ship sailing from the Chagos has been anchored at harbor for two days now. And its occupants don’t want to disembark. She rushes to the port. The man is right. It is there. The Nordvaer, she would recognize it among a thousand, with its white hull and proud carriage.

The barriers impede her approach, she cannot climb over them, and Tony is no where to be found. Only men in green fatigues loiter within the compound, feigning deafness.

“Les mo pasé. Mo bizin pasé!”

Her cries are futile; they refuse to listen. My God, the boat is going to leave, and she will not be on board, it’s going to leave without her, that’s impossible, she must find a way to embark, she must, she must.

Suddenly, two men approach and raise the gate. They’ve understand her, they’re going to let her board. But forceful hands pull her away, and a convoy of trucks drive onto the quay toward the Nordvaer. The gates close.

Something is happening, Charlesia can feel it. The men are negotiating. Long minutes pour away. Suddenly, a woman appears on the bridge. She approaches warily, almost afraid. She is doubled-over, protecting her chest. She seems to be holding something tightly in her arms, a blanket it seems, the way one might hold…My God, a baby, she’s protecting a swaddled baby at her breast. Charlesia looks at her. She resembles a woman she once knew. What was her name? Rolande? Rosemonde? No, Raymonde. Yes, that’s it, Raymonde. She lived in Salomon, and they met one day at the hospital in Diego.

Charlesia holds fast to the gate. She wants to call out to her, talk to her, ask her what is happening, is she knows where her mother and sister-in-law could be, she never got to say good-bye. But the woman is rushed into a truck with her baby.

The others follow. Many others. She has trouble believing her eyes, to many men, women and children descend from the ship. She never would have believed that so many people could fit inside. There is hardly any baggage. Very few carry bags, while some attempt to hastily collect the odd shirt or clay pot falling from their poorly tied bundles.

The trucks start up, pass through the gates. Charlesia wants to put herself in their way, but the men catch her and corner her against the iron bars. The trucks disappear at the end of the road.

She turns to look at the Nordvaer gently swaying, tied to the dock. He seems so old. The setting sun burns the horizon. He will never return to Chagos again, Charlesia knows it now.

“Hey, Nord, is everything alright? Are you seasick?”

As expected, Aunt Marlene’s interrogation set off an eruption of impish laughter in the courtyard. Sharp mockery pierced with affection.

With his back against a mango tree heavy with ripe fruit, Desiré lifts his head to glare at them, furious. As if now was the right time. As if he hadn’t had enough, with everything that put his stomach in knots right now.

Certainly, they had warned him. His cousin Marjorie’s first communion was a cause for celebration, but not for stuffing himself silly with brioches. It’s better to be considerate, and share amongst his friends and family.

He watches his cousin. She saunters around flaunting her frilly dress, carrying a basket festooned in white and gold ribbons. She distributes fat brioches wrapped in pretty embellished paper, and fills a pouch of envelopes and limp dollar bills, some red, some green, and they slide between her fingers before she clutches them tight with a grim look. He certainly can’t depend on her to share the spoils. She has a talent for business and he dare not grumble about it. But to return the favor, he can always run. One day, when he’s grown big, he’ll show her.

In any case, he’s already managed to take a fair share of the brioches. But even on this point, she must have shown kindly upon him, averted her eyes, maybe. He loves the light aroma of bergamot mingling with the pastry, and this, he thinks, constitutes the only true brioche, the only brioche deserving the name; slightly moist, with a white cross slashed into the crust, devoid of those few sugar crystals sprinkled on the cheap imitations in the bakeries that never fail to turn his stomach. The solid support of the mango tree didn’t quite save him from the carousel-dizziness erupting from his chest, climbing little by little up to his head.

“Nord, hey, Nordver, you don’t look too good. Are you getting queasy?”

Aunt Marlene is insistent and the sound of laughing ricochets all around.

He would like to lift himself up and go away, far from their jibes, escape the sickly sweet odor emanating from their glasses of rum. But he isn’t sure of his legs.

Tania fixes him with big, surprised eyes. She is pretty in her pink dress, too short. It must be a hand-me-down from her older sister. She sees her bony knees, covered in scars. A real daredevil, that Tania. And as curious as a mongoose.

“Why do they all call you that?”

He hears her voice in diffused echo.

“Your name is Desiré, right? Why do they call you Nord? There must a reason…”

He looks at her. There is yellowed splotch on the white of her left eye. He never saw it before today. But she is suddenly diminished by the butterflies of light blinking in his eyes. And the carousel accelerates. Her voice blends into the whirlwind:

“Well, are you going to answer me? What’s all this Nord-va-ear business about? I thought your name was Desiré. Are you going to explain it to me? Hey!”

He only has time enough to get up and rush toward the courtyard. On the dry dirt, he vomits, writhing in spasms, in bergamot perfume.

He had forgotten. Or, at least, so it seemed. Only a distant echo reached him now, from farther and farther away. The vague sensation of an eyelid stubbornly refusing to lift.

He is in his twenties, maybe, when the subject is finally broached again. Most likely during another family gathering, someone’s birthday, and naturally, the aunts make a strong showing. His ear had been drawn toward scraps of an animated discussion in the living room, energy brimming around the leitmotifs “return” and “compensation”.

That night, he had wanted nothing more than to go home, where he could finally interrogate his mother about what he had overheard. Finding himself alone with her at last, he made several false starts, groping for the best way to bring it up. She made no effort to wait for him. Instead, she went into the bathroom, than brusquely emerged ready for bed. She would be working early the next day, her boss needed extra help preparing for a big feast.

“Why do they call me Nordver? Does it come from Norbert?”

In the glass-doored hutch, in the middle of the hodgepodge tea service of green tea cups and multicolored saucers, between the track-and-field championship cup and glass Coca-Cola bottles collected in a barter with patiently-amassed corks, an old pendulum tick-tocked in slow motion.

“M’man, is it from Norbert?”

She tried to evade him, skirting around his armchair in a dash for her bedroom. But she was cornered against the low table adorned by a yellow-eyed cherub touting a conch shell. The evening’s heat pressed down against their heavy silence.

“So…it’s Norbert, right?”

She turned slowly back to face him. He could hardly see her eyes in the dim twilight.

“It’s Nordvaer.”

“Nordvaer?”

“It’s a boat.”

How genial it was for his aunts to call him a boat, another brainchild of their’s, no doubt. Like the little neighbor they had baptized Chauve-Souris, Bat, because she had tried to cut her eyebrows off to resemble her mother. The name stuck, and all the kids called her Sosouris from the moment they’d understood the craft of teasing. There must have been some foolishness involving a boat of which he had no recollection.

“The Nordvaer is a boat,” she reiterated. I was as if her voice had become disembodied, she wasn’t really speaking to him.

“Well? What else?”

“The boat you were born on.”

It took him a moment to comprehend what she was saying, her voice was so extinguished.

“Born? I was born on a boat? Where…here? On the beach? How? We didn’t have a house?”

He sees his mother’s back give a shudder.

“At sea. You were born on a boat at sea. In the middle of the ocean. And no, we didn’t have a house, anymore. We didn’t have a country, anymore. We had nothing.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

They had lost their house. And their country. That what she had explained to him. But how can you explain a thing you’ve yet to understand? Huge swaths of silence settled over her lips and eyes. The further he pressed, the more she detached. Her eyes no longer reflected him. Instead, he could make out something else. He didn’t know what exactly. A vague shimmering in the depths of her pupils, it resembled waves of heat trembling up from asphalt on hot day.

“What is this boat story all about?”

She looks at him. And she asks herself. How can tell him? Where to begin? His birth, the boat, the land, the other land. The truth. That thing that swelled in her mind and heart, in her belly and guts, every night. The land from before.

Before the fear, the incomprehension.

Before the solitude and the maddening anguish of the sea.

Before the thief-boat conjured sorrow from what should have been great joy.

Before this land, tall-mountained and indifferent, before its distant and scornful residents.

Before the anger.

Before the false resignation contrived to thwart the ineffective rage that threatened to explode into madness.

Before the sagren.

How could she possibly explain this to her dear Desiré, explain the nature of this wellspring she could barely contain?

~~~~~

Desiré was almost disappointed. He had imagined something grander, a menacing shadow, something like the dark and imposing mass of a slave ship that contained a world of anguish, gloom, agony. More than a century after the official abolition of slavery, weren’t the Chagossians treated in this very way; loaded up from the dock, crammed into the ship’s belly, tossed aside without another thought, in the hope that they’d crumble into a brownish dust and get conveniently swept away by a cool sea breeze?

The Nordvaer had no resemblance to all those hideous, sinister representations he’d imagined. In the photo it was a boat, perfectly white, with not one distinguishing feature. Except for its size. Very modest. Too small to believe it had really transported all those souls. There must have been an error.

Desiré had the idea to contact the National Library of Norway, and it turned out to be the right path. After corresponding with a few of the Library’s authorities, above all the director, he finally got a match. And a letter.

The envelope was crumpled, the corners sort of dog-eared and the seal beginning to come unglued. He tore open the brown paper hungrily and discovered a sheaf of printed pages. It was a copy of an article on the Nordvaer signed by T.G. Bodegaard, who had published it in a maritime journal.

“Dinner’s ready.”

His mother’s voice. She is standing behind the curtain that separates his bedroom from the family room. Desiré stuffs the envelope under his pillow and rushes to join her. In the kitchen, on the plastic tablecloth covered in geometric shapes, she’s set down plates of steaming rice. They eat in silence, listening to music on the radio. Desiré senses that his mother is waiting for him to speak. But he’s too eager to read the article, he takes a few quick bites of his food, rises, goes outside to give his scraps to the dog.

His chain has broken. It’s hanging, abandoned, by the low wall that stretches past their neighbor’s yard. The dog has figured out how to escape again. Desiré scours the neighborhood for hours looking for him. Towards midnight, he finally finds him, quivering outside a house that he knows, senses, contains the dog-love of his life. Convincing him to come back home is not easy.

It’s almost one in the morning when Desiré settles into bed, the precious envelope in-hand. Tired, he has to make an effort to concentrate on the words, searing themselves into his eyes.

He holds the screams inside himself. They echo throughout his body, their deafening waves scare away the birds that dare to perch nearby. He tried to confine those strange vibrations, to capture them in the sand, but they fragment the water and take shape again. With even the smallest cry of a bird, silence crashes inside his weathered body.

Reawakened, suddenly. They’re all there. Everyone. Dozens, hundreds, surrounding him, pushing against him, hungry to escape him, but obliged by their desire for a breath of fresh air to press in tight against his walls, they want to escape the press of so many bodies, staggering, colliding.

He never could have believed all this. That he was actually able to carry this excess of bodies without exploding. And yet, he’d proven his endurance through a parade of voyages. Built in Elmshorn, near Hamburg, he’d sailed on behalf of one of the coastal navigation companies of Bodø. In Norway.

1958. A beautiful year for him. Every week he forged across the distance between Trondheim and the Lofoten islands without fail. It was always an agreeable convoy of passengers, no more than a dozen, often elegant British tourists and always polite. On the return trip he’d carry a shipment of freshly caught fish and seafood. He was always proud to successfully regain those islands, flaunting their sheer and perilous cliffs. Ah, those stately lands, that cold and lively sea. It was something totally different than this. Than here. No one was gutted with the shock of dépaysement, with the suffocating impression that he’d felt since the first time he set sail, unhomed, unmoored, into that tepid water; those salty, weighty, Southern seas.

Years passed coming and going without a hitch, without delay. Then the change, the shift. The train, the train’s arrival made him useless, made him a relic. That over-glorified, noisy, polluting pile of scrap metal replaced him without a hint of due process.

Men’s ingratitude sold him off, to the other side of the world. To the Seychelles’ government. His first voyage was a nightmare. He thought he’d dissolve as he reached the equator. But he had a solid constitution. He was used to it, had even learned to enjoy the challenge. Certainly, it was another kind of existence, he sailed across the Indian Ocean, between Mauritius, the Seychelles, Chagos, transporting provisions and products like oil, brooms, and brushes all made from coconut, and even passengers from time to time. He had become essential again, had rediscovered his purpose, he’d begun to enjoy the warmer disposition of these people; they were lively, they served him well.

By the end of the sixties, he was chosen to be pictured on a postage stamp issued to celebrate the anniversary of the British Indian Ocean Territories; the famous BIOT assembly of British colonies of the Indian ocean. With the Queen of England’s profile watching over him on the top left corner of the little square stamp. He and the Queen of England brought together. It was more than worth the pain of leaving his Norwegian seas.

Then he had to endure hard labor. Without a doubt they had grander ambitions planned for him, since he was retrofitted with an upper deck that instantly multiplied his carrying capacity. It was true, his silhouette was changed, but he was impatient to meet with this more glorious destiny laid out for him.

He started to pick up on strange murmurs here and there, on board. Things were clarified, one night, mid-journey. He heard them discussing it. Were they going to force him to exile those people he had grown to enjoy? He couldn’t play a part to their exile. A cyclone, a tempest, a tsunami would come and capsize him, rid him of these schemers, eject them all, drown them, together with their wretched schemes.

But he was left powerless.

They loaded him up recklessly, crammed him with helter-skelter bundles, men women, children, all shoved in without care or consideration. He would’ve swelled wide, broadened his hull, given them a little more space, a little more dignity, if he could’ve, if he knew how.

Throughout the entire crossing he was flooded with words, a haunting ritual: the national hymn of Norway. Ja, vi elsker dette landet, Yes, we love this country. Was this it, death, these faraway memories rushing forth? Was this the herald that opened wide the gate of his demise, his plummet to the bottom of the sea, under the weight of all these people, the weight of suffering that left them all prostrate in his hold?

He remembers a dog that chases after him, barking, and a child that he carries on his bridge, the child lifts his hand, both hands, he lifts his cries and his whole body toward the dog. The dog is bolting, energized by determination, on three legs, the dog is an absolute frenzy on three legs, a distended engine that will not relent, that refuses to surrender. That dog chases him because he’s carrying away the child, like a thief.

The dog runs parallel to his wake and follows him for as long as he has sand beneath his paws. Suddenly he stops short, halted by the sea. And watches him go, erect on his three legs, his silhouette rigid and pitiful, the final look-out with nothing more to watch over. Nothing more to hope.

He doesn’t know how long that dog stayed there after distance diminished him to what could be mistaken as a tiny bird, poised over waning memory. He doesn’t know if he laid there, in place, or if he left with his head lowered. He he survived, for how long. How. With three feet and no eyes. Yes, he carries the eyes of that dog, senses them, incrusted there in his hull, starboard. Everywhere, he’s carried them everywhere, across the seas, as far as he could flee, he even considered drowning them, drowning himself, but in vain. And all that water washes but doesn’t protect him. The eyes that burn him, two torches piercing his side, wrenching open his shell, reaching into his very depths.

He heard them talking about it, in the captain’s quarters, they killed them all before they weighed anchor. All the dogs. They gathered them all up, surrounded them. A few tried to escape. They didn’t get far. Driven back with heavy blows from the men’s clubs. Forced into an incinerator. They closed the door. Packed the oven’s mouth with dry straw. Ignited the fire.

He knows he saw that dog. A survivor, no doubt. They persist, those eyes, howling, louder than a dog that senses the approach of death, with more insistence, more desperation. And those howls mix with cries, silenced cries buried inside human throats, cries unexploded because they’re unable to pass through mouths of clenched teeth.

He heard them all. Hoarse, raw, punctured by fear and incomprehension. He’s never stopped hearing them, no tempest could ever silence them.

They resound in him, those cries silenced, suffocated at the bottom of those men’s and women’s throats, clutched there so fiercely that salty tears flow from their eyes with the effort.

That was the day he started to rust from inside.

If only they had sunk him. They’ve been known to make reefs out of boats grown too old to serve. Maybe beneath the water he would’ve finally been able to stifle those cries, weighted by dark sleep. They settled for running him aground, like a crude piece of driftwood, and the birds, screeching and garish, made a sport of mocking him, fighting and squawking for a place on his hull, covering him with their yellowish feces then flying off again.

Sometimes he couldn’t stop himself from thinking about the Catalina, a twin engine, beached like him. Over there, on the shore of Diego Garcia. Nose pointed to the sky, body awkwardly slumped in the sand. But he, at least, was played on by children, and served a purpose.

The children. All those years later, the trace of their frightened tears remains persistent in his mind. And there had been that hollering, singular among them all. He had never heard the likes of it. He’ll hear it until his death. The howling of an infant seeing the light of day. His whole being trembled with it. He had wanted to sound his alarm, to ring out the joy of the occasion. A baby. A baby was born in my loins. In my belly. I’ve helped give him life, bring him the light of day, I’ve sheltered him, I’ve cradled him. But they carried him away, him and all the others.

island, what’s left to us

map’s traces

lives veiled in violenced history

what’s left to us

to cry, to write

imbecile hatred

and history’s chain

Diego, your name on the white-washed map

Diego, love

Diego, bitter

Diego, dying

—Mélangés

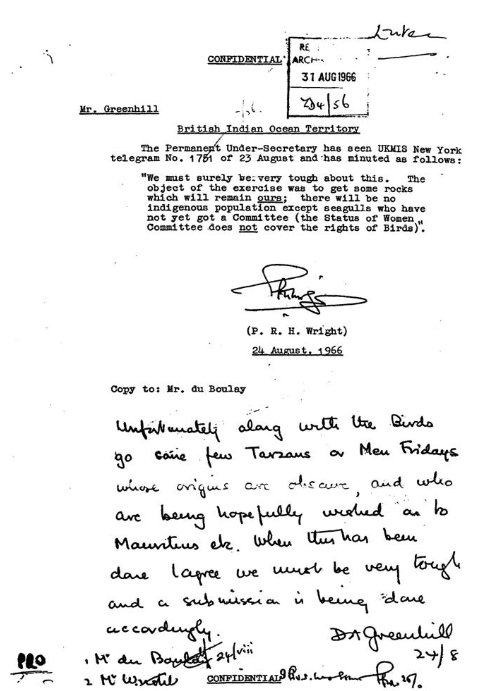

“The object of the exercise was to get some rocks that would remain our property; to eradicate the indigenous population, excepting seagulls who have not yet got a Committee (the Status of Women Committee does not cover the rights of Birds). Unfortunately, along with the Birds go some few Tarzans and men Fridays, whose origins are obscure, and who are being hopefully whisked on to Mauritius.” –Extract from a note sent in August, 1966 by the Colonial Bureau of London to the British Mission of the United Nations.

Diego Garcia, 1963

The brass bell tolls, resounding in echoes through early morning’s tepidity, and when it quiets at last absence reigns. It’s five o’clock, Charlesia gets out of bed, still dressed in sleep, walks to the front door, opens it just enough to slip outside. Last night’s darkness has not yet lifted from the humid land. But she doesn’t need light to make her way to the adjacent kitchen, even deprived of sight her bare feet guide her true, four steps then her hand extends, opens the sheet-metal panel. The matchbox is in its usual place, on the shelf above her head. She pulls out a match, feels for the sulphured end with her fingertips. The sudden glow of flame makes her blink. She holds a pot full of water up to the light. Alas, the tin of straw tea is almost empty, there’s just enough for this morning, she knew she was forgetting something when she went to the shop the other day. It won’t be open today, but Clemence or Aurelie will let her borrow some until Friday.

The drink is paler, more diluted than usual, but it’s hot and sweet, the way she likes. She finishes her cup in one gulp, serves one to her husband who’s just come to join her.

Back in the hut, she slips on the dress laid out on the chair by her bed, takes her hat from the table. She can hear her children’s rhythmic breathing in the adjacent room. Mimose lets out a chuckle. Even in her sleep, she laughs! She was born exactly eight hours after the death of her great-grandmother. Everyone in the family says she inherited the elder’s vibrant sense of humor. Charlesia leans over, takes in the smell of warm sleep, smoothes the girl’s hair, sets out to join her husband waiting for her, lantern in hand. A little later, at seven-thirty, her neighbor Noeline will wake up the children and bring them to school, along with her own.

Charlesia and her husband move swiftly to catch up to the other lights moving toward the center of the island, swaying along the path.

“Alo, Charlesia, Serge, ki manyer?” A neighbor welcomes them as they join, asks if they’re well.

“Korek Tasia, tu?” Charlesia responds.

One after the other the halos of approaching lamps converge on the path, each signaling the presence of a new arrival, each one greeted in turn. The dance of sparks gradually extinguishes, replaced by the pail light rising from the horizon, rousing the chattering of birds in the tall palms. At five thirty, the usual little crowd is assembled in front of the office of the administrator, who arrives promptly, wearing shorts that fall just to his knees, thick socks pulled up over his calves, with a domed hat tucked under his arm. ‘Hellos’ are exchanged. The two men in charge divide everyone up according to the thirty-six types of work on the island. Some are sent to the Big House where the administrator’s wife decides if they’ll clean or work in the kitchen, while others are relegated to maintenance jobs on certain parts of the island, and others still are sent to plant or harvest crops, or tend to the livestock. But the majority of them are assigned to the coconut groves, usually to work on either the dehydrator or incinerator crews.

With about fifty other women, Charlesia goes to work on the dehydrator. They had amassed hundreds of coconuts the day before, so were now tasked with decorticating them all, one by one.

“Alé bann madam, travay largé.”

The work begins with familiar organization. Charlesia takes hold of a fat green coconut, lifts it above her head, smashes it violently against the cement platform where it cracks open, and water flows from it down the hill, into the ocean. She thrusts her fingers into its new fissure, tears the husk, its fibers resist before finally breaking apart, then she sets it aside, open-mouthed, to dry. The movements string together. The coconuts accumulate.

“É Charlesia, tan dir toi ki pou fer séga sa samdi la?”

Charlesia lifts her head. Her companions have all stopped moving, waiting to hear her response to Maria’s question with one shared, anticipatory breath. Yes, she’d like to host the Saturday sega at her place this week, but she’s not sure if it will be possible. Her belly has started to grow heavy. She mustn’t overtire herself. And there’s the matter of the extra shifts Serge was asked to take on, which seems more likely with the incoming shipment of provisions at the port.

Work begins again. Little by little the air fills with the succulent green and gently sweet smell of coconut, as the juices evaporate into the sun.

Charlesia picks up one last coconut, it had rolled off to the side, and with one strong blow she makes it explode. She exhales, draws her feet under her body, puts one hand to the ground and lifts herself up while dusting her skirt off with the other. It’s time to leave, she has to ensure that a number of things get done before evening.

First, she must see Serge. She hurries toward the incinerator; in fact, she need only follow the strong odor of burnt coconut fiber to locate it. Surrounding the huge, slender oven men busy themselves in a heat that liquefies the skin and dries the eyes. Some of them continue to stuff the gaping mouth with dry hay, feeding the fire which roasts the coconuts, to then extract their essence: the copra which earned Chagos the nickname “oil islands”.

Charlesia locates Serge on the other side, his silhouette blurred by the vaporous haze emanating from the oven.

“Serge, ki to pansé si nou fer séga lakaz sa lamdi la?”

He pauses in thought. He’s loves hosting the séga festivities at their home, but perhaps she should take care not to overtire herself. And their reserve of baka and kalou libations likely won’t be enough for the crowd, and the alcohol percentage won’t be strong enough if the fermentation process is cut short. Okay, they’ll talk about it later, Charlesia says. She trudges down to her hut to retrieve her fishing rod. She promised the children a good catch of fish for tonight. Passing by the school, she hears them all, the full choir of them reciting the alphabet under Miss Leonide’s firm direction. She stops at the window. Ah, Mimose isn’t there. Lately she’s begrudged having to go, says she’s too big now, that she’s annoyed in that mixed class of all-ages, she’d rather rollick around the island, free. But the administrator insisted: children must be in school during the day. Mimose has surely made up some story to save herself, on the pretext of some note of excuse or other which—surprise, surprise!—she’ll fail to produce if pressed.

In any case, she’s not in the hut. Charlesia glances around, takes the fishing pole propped in a corner, reconsiders, then doubles back to drink a glass of water. She tidies up a few things the children left around, and prepares to leave.

“Kot mo sapo?”

She combs over the place without finding it. Her hat. She’s sure that she set her hat down in its usual place when she came in, on the back of the chair against the wall by the door. She’s certain it was on her head when she left the coconut grove, so it must be here. She hears a giggle from behind the door, Mimose’s no doubt, impossible to mistake that impish trill. Of course, she must have taken the hat to go gallivanting on the beach with her little gang. Charlesia reminds herself to weave one for her soon, just for her, with a broad brim and a pretty ribbon to tie at her nape. She looks out the window. Mimose is already out of earshot, she runs gripping the hat against her curly hair, as it threatens again and again to fall off. Charlesia sighs, picks up the red handkerchief draped on the table, nimbly ties it over her hair and leaves.

On the beach she sets down her fishing pole for the time it takes to tie up her skirt, secure it by her hips. White seafoam laps around her ankles. She wades into the tepid water until it brims up past her thighs, casts her line, the thread chirps through the air before the bait plunks beneath the surface. She keeps still, her body becomes one with the sea, the sand beneath her feet, the sun warming the fabric of her headscarf. Beyond the zones of green-then-blue, her eyes drink in the stretch of white, with its belt of coconut palms, their island, behind her, before her, a jeweled backdrop; comforting, calm. She waits.

The line plunges down. She reels in a spinefoot fish speckled with grey, which thrashes as she dispenses it into the canvas sack slung over her shoulder. And before its strength is completely exhausted, it’s joined by a blacktip grouper weighing at least two pounds, enough for a satisfying bouillabaisse, flavored with a handful of bilimbi cucumber fruits plucked from a nearby tree.

But Charlesia wants something else. She steps out of the water, crosses the peninsular strip of land to the other side. Nearer to the outer waters, where the sea deepens, where the sea is a deeper blue, charged with an energy that comes from afar, from beyond the horizon, from another world.

In a few minutes, Charlesia catches three banana fish, their firm white meat is her favorite. This will do the trick for tonight. She climbs back up to the beach, settles into the far-reaching shade of a takamaka tree. From the bottom of her pocket she takes out a piece of wood with two nails driven into it, and with brisk strokes rubs this against the fish’s grey flesh. Iridescent scales fly through the air, stick to her fingers.

She then walks into the forest, in search of young growths of coconut palm. She pulls away the palms to reveal the tender hearts, and chooses the best among them. Returning to her hut, she sits outside the front door and peels them.

She thinks of the baptism of her sister’s youngest son. She’ll have to ask the administrator when she can expect the priest to come to Mauritius. It must be almost a year since his last visit. He needs to return soon.

The milky juice coats her fingers, the right consistency. She rises, throws a few branches and twigs between the four flat stones of the hearth, strikes a match. She waits until the fire is well-kindled before setting her karay pan with its domed top over the heat. Flames lick the black cast iron, heating it gradually. She poises her hand a short distance above it. As soon as she feels her flesh warm, she adds the bowl’s content to the pan and gives it two spoon-stirs. Yes, she needs to talk to her sister soon, to discuss the preparations. There are a few scraps of white satin left over that her cousin brought from Mauritius. She could make a pretty dress for the baby’s church ceremony. They’ll have to get a bit of pink ribbon from the shop. Maybe hers will be born when the priest comes. Then they could have two christenings at once. The administrator will certainly want to give them a nice hefty pig, the kind with tender, juicy flesh fattened on coconut pulp and sprouts.

The pan’s sizzling calls her back to the hearth. The liquids have nearly evaporated, cream stagnates at the bottom, tiny pools of oil float on the surface. She waits a few seconds, takes the karay by its handles from the fire then pours its contents slowly over a tin sieve, and collects the golden, fragrant oil that pours from it into a bottle. She sets the filets of fish into the karay, well-coated in the oil, and they immediately react with the hot oil, little bubbles of heat and steam leap up in a crackling crescendo as the skin begins to crisp. Then she adds a touch of finely shredded coconut and a variety of spices.

In the distance she can hear the joyous clamor of school day’s end, and all five kids burst out of class without wasting a second.

“Mimose koté? Tonn trouv Mimose?”

No, she hasn’t seen Mimose. Well, hardly. When they ask where they can find her, it’s a kind of unspoken code, a complicit ritual, because they know exactly where she is. Charlesia tries to keep them there, but the raucous little tribe has already darted for the beach, in unison. Only the youngest boy hesitates, approaches her, throws his arms around her neck, plants a wet kiss on her cheek, then trails after the others hollering for them to wait up. Charlesia watches him disappear, he’s the most affectionate of the bunch, he reminds her of their other child, taken from them three years earlier by an evil fever that could not be quelled. She’ll carry flowers to him on Sunday, in the cemetery by the church.

The fragrance wafting from the karay leads her back to the hearth. Her seraz is cooked to perfection, she extinguishes the fire, then brings some order to the turmoil of backpacks strewn about by the children in their haste for the beach.

“É Charlesia, vinn get sa!” Serge beckons excitedly from outside. He must have something to show her. Charlesia sighs, sets down the backpacks, peers out from the threshold. He’s there, down below, with Rosemond and Clément, pulling up a big stingray by one of the fins. Charlesia assures herself that the long tail is lifeless, grabs the other fin to help Serge drag it up to their hut. Spread out in the grass, the animal’s wingspan stretches wider than Charlesia’s extended arms. Its slate-gray skin, edged with white, is beautifully supple. Serge strokes, presses, measures it. He could fashion two beautiful drums from its hide, which would resonate under the beat of the men’s palms, and drive the rhythm of their upcoming séga soirées. And there would even be enough of the flesh leftover to share with the neighbors.

Charlesia leaves Serge to his task and descends toward the beach. The children are on board the Catalina. The little broken plane marooned in the sand points its ridiculous nose up to the sky. It crashed there one day, she doesn’t remember when anymore. Some say it happened sometime during the Second World War, when the British used Diego as a telecommunication relay station. Others claim it’s simply a rumor, and affirm that the Catalina was just a pleasure plane that crashed in a bad stroke of luck. She herself has no idea which is true, she simply has the impression of it always being there, part of the landscape, like a fallen coconut palm that the children scramble over, waging little attacks and, imagining themselves as fighter pilots, making the engine sounds with their mouths. There they are, maneuvering through the sky, sitting astride the rusty fuselage, corroded fuselage by the salt air.

Charlesia watches the children play, her legs outstretched in the sand. They climb from the cockpit then disappear into another cranny like a flock of happy songbirds. The sea has pulled back, the shore sighs easily under dusk’s endless rosy glow. The children suddenly leap away in unison, farther down to the left, toward the tortoise cove. Seeing this Charlesia jumps to her feet and chases after them, hollering in an attempt to stop them in their tracks. They’re going to gorge themselves on tortoise eggs and ruin their appetite for dinner.

Three huge tortoises lay motionless in the sand. The children surround them, isolate one, the plumpest, and team up to carry it back. She fights them a bit, tries to push them away, twitching her flat feet, but soon she surrenders with little resistance. Beneath her the children reveal a beautiful treasury of eggs, and everyone picks at them at once. Charlesia takes one, too. She weighs it in her hand, cracks it, peals away the bits of shell and gulps the warm contents, letting the smooth liquid pass against her cheeks before swallowing. At her side Mimose eats four of them, the shells form a little heap at her feet. Charlesia straightens up, remembers why she chased after the kids. It’s time to go back. Serge is waiting for them.

On the coconut fiber rope strung across two posts on the left side of their hut, the dried laundry has been pushed to one side to make room for the stingray hide, suspended there like a great grey cape. Serge washes his hands at the faucet, makes known he’s hungry.

Charlesia relights the fire, the smell of fish curry mixes with the mosaic of aromas in the falling night. Standing in front of the door, Serge pricks his ears toward the sound of approaching steps, preceded by a lantern’s oscillating light.

“Alo Serge, korek?”

It’s the Commander’s voice asking after Serge, confirming the apparition of his face illuminated from below, like a mask of deeply furrowed grooves crisscrossing over themselves. The administrator charged him with assigning a few men to work extra early the next day to clean the coconut plantations on the other side of the island. Serge accepts with a nod. Charlesia asks the Commander to stay for dinner. He’d like to. The fragrance of the meal-to-come cannot be contained by the karay, wafts temptingly in his direction. But it will have to wait for another time. He still has to gather up a few more men.

Charlesia doles out great heaping spoonfuls of rice onto each tin plate, then coats each plate of rice with the unctuous seraz sauce. Seated in a half-circle around the hut’s door they eat in silence, their movements slowed by thoughts of sleep.

Diego Garcia, 1967

The call came early, just shortly after the bell tolled, as it did every morning, summoning everyone to the administrator’s office door, where he’d distribute chores for the day. The are was sweet. Charlesia had just settled in to her place at the dehydrator and had begun to decorticate her share of coconuts when she’d heard the very welcome announcement, mixed with an eruption of satisfied cheers sent up by her comrades.

Three months had flown by since the Nordvaer last docked, and there he was again, like clockwork. The men stationed as look-outs in the tallest casuarina trees along the shore had just begun to bellow the news of their sighting from far off, a tiny tear in the uniform line of the horizon.

“Ship ho! Ship ho!”

Their shouts echoed throughout the morning as they tracked the Nordvaer’s progress around the jetties’ wide curve till it drew alongside the port. For the last few years the captain made habitual use of porting techniques that the Chagossians called maneuvrage. Time was marked and steadied by the comings and goings of the ship. Everyone knew, for example, that about three months had now passed, which was important for just one reason: a new shipment.

The captain anticipated his arrival in Diego with particular excitement, before moving on to Peros Banhos and Salomon, the two other principal atolls of Chagos. Even his ship seemed to hasten, as if anxious to get through the seven or eight days of navigating so that he could set sail for the north again, toward the center of the Indian Ocean, halfway to the Mozambique canal, to arrive at last, finally in view of the Chagos archipelago, which materializes like a dream-turned-reality on the horizon. Each journey felt like arriving in a new world, as soon as he approached those islands he could breathe easier, differently. If he’d had the chance he would have loved to extend his visit well past those brief stop-overs.

He’d wondered if he should try to find a job on-land, to stay there, to share in that simple existence with the people he’d come to recognize and appreciate. But he knew he risked feeling claustrophobic. For him, the sea was his territory. And the promise of land. An intense sensation filled him every time he came close enough to smell the island, a perfume of land and salt carried on the breeze, so different from the harsh and saturated odor that wafted from the continents, too big for the winds to sweep them through.

He could recognize that Chagos perfume even if he’d embarked blindfolded on a ship with no knowledge of its coordinates. Sure, Mauritius had its scent, sugary like its cane fields that extended, almost monotonous, up to water’s edge. But Diego had something all to itself. Toasted bark. Springwater. Sand. Sweat.

From much farther off than his sense of smell could carry him, when Chagos appeared as no more than a black dot held captive in his telescope, an indefinable feeling overcame him, approaching a port he couldn’t love more, transient as he was, it was a place of comforting permanence. But today that feeling was unsettled, and as he neared the archipelago, the crux of his stomach pinched tight.

The ship’s arrival was nonetheless a lively event, a morale boost for the whole island. On this morning, the Commander had assigned the men to prepare for the disembarkment. They divided into groups, ready to load their shoulders one-by-one with the newly arrived crates and bundles of supplies, meant to last until the next shipment in three months’ time. The sun struck against their bare torsos, conjuring a sheen that contoured and defined taut muscles; a glistening of deep bronze skin. Their antlike comings and goings between the hull and storehouse, a three hundred-meter trip, were heralded by jeers and bursts of laughter, and lasted two solid hours.

After he supervised the unloading with the administrator, the captain greeted a few familiar faces, and climbed back into his ship to finish with the usual formalities. As the sun began its descent toward the horizon and work was done, he made his way to the administrator’s house, where he was normally hosted until his next departure, which would be the morning after next when he’d move on to Peros Banhos, then several cable-lengths from there to Salomon. With its triangular roof and pretty windows dressed with green shutters, the Big House stood out among the tiny scrap-metal huts scattered throughout the flat land, shadowed by coconut trees. The administrator’s wife stood at the front door waiting with a warm smile on her face to welcome the captain.

Her candle wax-white skin, framed by her blonde hair, had taken some color since she arrived on the island almost one year ago. The captain enjoyed his conversations with this woman; especially after her initially aloof, haughty demeanor gave way. She was quite different from the previous administrator’s wife, who most considered idiotic beyond redemption.

The administrator, in turn, welcomed him with his strong, jovial voice, proudly inviting him to taste his kalou palm wine, fermented himself. The first time he tasted the stuff, he thought he’d lost his tongue and palate forever. His men had offered it to him, obviously as a test, and despite his initial aversion to the strong smell of fermented coconut wafting from the tumbler, he swallowed its contents in one gulp, surrounded by the delighted jeers and hollers of his men as they good-naturedly clapped him on the shoulder. With his held tilted back, he felt the liquid set fire to his throat, wondering for a fraction of a second if he should spit it all out, fast, before the flames reached into his stomach and destroyed his guts. God only knows what that would provoke. Suffocating, unable to breathe, the others roared with laughter and came to his rescue with a few brusque slaps to his back. He was sure he wouldn’t survive. To do him honor, as they say, they’d served him one of their oldest kalous, and had steeped for three months. When he managed to regain his breath, he didn’t fail to notice how his taste buds seemed to awaken,

Their three children, faces smattered with freckles, burst with laughter as they return home from the beach, and it’s clear that their stay on the island has filled them each with a confident vitality. The administrator listens to them distractedly. He didn’t realize how festering the political problems had become. He finds himself torn. He wonders if Mauritius wouldn’t be better off as a British colony, rather than embark on the treacherous road to Independence, and asks himself how much faith he should put in the new leaders who campaign on the promise of making Mauritius a state of India.

The captain continues to nurse his glass of kalou, skeptical. He’s not of the same mind. But he admits that his companion is convincing. Several of his acquaintances have already committed to leave Mauritius in search of better prospects in Australia. One of his cousins, half-joking, asked him if he’d take them on his boat, just in case. He tends to think people are over-reacting, anticipating more danger than reasonable. To his mind, everything will happen as it should, and he’d prefer to maintain that conviction. That the time for decolonization is now. That Mauritius is more than ready to take charge of its own destiny. But of course, it’s not unreasonable to keep a back-up plan in mind, if things go bad. And the administrator has already figured out that plan. He and his wife have family in France and South Africa. So they won’t have much of a problem, either way. But he’d prefer not to dwell on events he can’t change, or waste time uselessly worrying.

The sun has begun to drip toward the sea’s horizon, for a brief instant bedazzles the last wisps of clouds. A first star has appeared to the West. The floorboards creak as a woman carries a plate of fried fish, places it on the low table between the two men. The administrator reaches for the crispy skin with his hand, still too hot to be touched.

“And have you told them, yet?” The captain asks.

The pitter-patter of a lizard sounds across the tin roof, where waves of heat still undulate and the absorbed heat begins to exhale. The administrator brings a glass to his lips, empties it in a single gulp with his head tilted back.

Tell them? What is he supposed to tell them? None of the information he’s received has been clear. So far he’s under the impression that the company will end its activities soon, that he’ll be required—in anticipation of this shut-down—to gradually send them all to Mauritius, without warning them. Explain it to them? He hasn’t understood any of it, yet. His contract as the island head expires in a few months. He wants to be gone before it lands on him to make the announcement.

The captain shakes his head. Distantly, the sky is veiled in a papery muslin transparence, the air as light as dream. The silhouette of a woman with a child straddling her hip slowly crosses into his field of vision. She’s walking, determined, to the front of the Big House.

“Rita! Ritaaa? To la?”

The two men hear her voice ring out through the house. The child on her hip prattles sweetly. Another woman responds from inside the house, rushing out of the kitchen where she’s been working.

“Yes Charlesia, mo la mem. Ki to lé?”

The captain and administrator have no problem following the conversation in the still air. Charlesia has come to ask Rita if she could watch little Rico the day after tomorrow, so that she can go to the shop for her rations. Rita would be happy to, but her husband, Selmour, has already planned to go fishing then, and since she has to host that evening’s sega, she’s afraid there will be too much to do. Perhaps she should ask Leonce, who loves Rico and could go collect her own rations after Charlesia returns.

The two women bid farewell to each other with a quick kiss.

Silence settles on the veranda. The administrator leans over the small table and pours himself another generous glass of kalou.

“Their big sega is tomorrow night. Go have some fun. It might be your last chance to see it,” he says to the captain.

A gecko’s cry resounds through the twilight, his tongue clicking doubtfully.

Seven-thirty. Sprawled across his mattress, little Rico watches a bird nestling into the heat of the straw roof with rapt attention. Charlesia didn’t need to go find Leonce. She’s standing at the door. Rita let her know the day before, and she didn’t need to be asked twice. She never misses a chance to play with the boy, she loves to tickle him into fits of laughter and shower his round cheeks with loud, smacking kisses.

“Monn fini donn li boir. Li pa pou soif aster la,” Charlesia mentions to Leonce.

Yes, the baby just finished nursing at her breast, he shouldn’t be hungry for a long while. At eighteen months old, he still drinks his mother’s milk to his fill, but she knows it’s time to wean him; he hasn’t been gentle with his new teeth.

Charlesia puts on her straw hat, takes her large bag made from woven coconut leaves and sets out for the store, the only one on the island. As on every Saturday, it seems like the whole island has converged there at precisely the same time. Today the crowd hums energetic, the new shipment on everyone’s mind. Daisy and Eliane are being served nearby. Charlesia is patient, chatting amiably with Laurencine, who mentions that she and her husband have decided to move across the island to a place on the Eastern point, to the house in which Mea and Augustin used to live. She doesn’t know where they’ve moved; perhaps to Salomon. Or maybe to Mauritius, where they were said to have family. In any case the administrator said their house was available.

The shopkeeper calls Charlesia to the front. She hands him her bag, which he fills with her share of the week’s rations: two pounds of rice, five and a half pounds of flour, one pound of lentils, one pound of dahl, one pound of salt, two bottles of oil.

“Ou bizin lézot zafer, madam Charlesia?”

She ponders for a few seconds. They need a bar of soap, too. There’s still some milk left. Definitely tea. And some coffee, she’d used the rest of last month’s coffee ration during the death vigil for old Wiyem. Cigarettes and matches. The shopkeeper serves her, tallies up these last items and records it in his book. Then he moves to the next in line.

“É missié, ou pa finn blié narien?” He calls out wryly.

The shopkeeper always teases Charlesia, feigning innocence until she scolds him. She holds out her bag to him again and this time he deposits the two liters of wine, reserved for her and her husband, between the rice and flour. She knows that Serge thinks her taste for wine is too pricey for their means. It costs one rupee fifty per liter and he only makes thirty-five sous for each full day of labor. But she likes it better than the baka or kalou, that seem to lick the throat with flames with every sip. She’ll savor her glass of Monpo tonight, sweet and refreshing on her tongue.

Some men have come along to help the women carry their goods. Serge isn’t among them. Charlesia calls out to Rosemond.

“Serge kot été?”

“Li paret inpé fatigél Linn res la ba mem.”

She hadn’t noticed his fatigue before. She told him not to drink too much baka last weekend. She’ll have to keep an eye on him. Charlesia hoists her bag onto her shoulder, sets out on the path back home. Leonce and Rico have left to play with the children on the beach, but Serge is sprawled across the bed, curled onto one side. His loud bursts of snoring leave no doubt: he is deep asleep. Charlesia swears. He’s left a full quarter of pig outside in the sun, delivered by the administrator this morning, who’d killed and butchered the animal himself. She’ll have to clean and portion it soon, and he knows she doesn’t like that job. But he doesn’t either. But it needs to be done.

She tries to wake him but he grumbles that he doesn’t feel well, rolls to his other side and falls back to sleep. That’s that, surprise surprise. She saw this coming so, for dinner, took a chicken from her coop, with a fresh brèdes sauce, but it’ll be a pity to let the pig go to waste.

But now she has to put away the groceries. And she’ll have to mend her long skirt for tonight. It was torn during the last séga on a nail jutting out from a doorframe at Mea’s place. She spreads the froth of white cotton ruffles across the children’s bed, three good meters of wispy fabric, threads a needle, repairs the tear. She can hear Serge rustling in his bed nearby. After a moment he sits up, goes out to the yard to splash his face with water. She watches him from the window as he turns back to the cottage. It’s true, his features are particularly drawn today. She’s going to make sure that he drinks a tonic of fresh coconut water; nothing matches its healing qualities.

“Ki to gagné?”

Nothing, it’s nothing, he murmurs in answer as he enters the kitchen and reaches for the butcher’s knife on the counter. He sits next to the pig quarter on a flat rock and begins portioning. But Charlesia catches him, from time to time, massage the right side of his torso with the palm of his hand. Ok, if he doesn’t get better she’ll bring him to see the nurse. Mule-headed as he his, she’ll have to drag him there, surely, but she’ll have the last word.

For now, she takes the knife from his hands. Go on and rest, now, she’ll take finish up with the pig. Nope. Out of the question. He started the job, he’ll finish it. Charlesia hesitates then goes out to the backyard to trim a few sprigs of thyme and some brèdes leaves, for a nice bouillon to accompany the pig fricassee, clearly there’s plenty that needs preparing before they go to the séga.

The first beats of the drum rang out at eight o’clock, when Charlesia and Serge joined the others on the path leading to Tasia’s hut. They converge with the dozens of others, distinguished by their dancing lanterns, chatting jovially as they made their way to the promised night of celebration, where they would be until sunrise.

In the yard, the men have set a pile of straw on fire, it crackles and sparks. All evening, they’ll take shifts tending to the flames which they use to heat their drum skins. In a corner Tasia’s son Tonio proudly shows off his instrument. He made it with a beautiful manta ray skin, stretched taut over the rim, that he’d caught two weeks earlier. He had followed Oreste’s instructions perfectly, carefully washing the skin to remove the salt, hanging it to dry, then moistening it with fresh water before he stretched it cross the wooden circle carved from a fouche peepal branch.

Oreste has mastered the art of crafting beautiful instruments that sing in deep resonant tones at the slightest touch, vibrating through the air. On a recent trip to Mauritius they told him how, over-there, they make a similar kind of drum called a ravann, but it’s made with goat skin, far less vibratile to his touch. For him, nothing equaled the ray’s supple membrane. Tonio agrees: for the last drum he made, he used a donkey hide, and it doesn’t even come close to matching the beautiful tone of the drum he boasts tonight. From the moment he nailed the skin to the wooden circle he felt as if it responded, reacted to his touch. It resonated with a strange impatience as he cut the edges at regular intervals, slowly introducing it to the circle, over small iron rods, the four pennies that would bring a tinkling sonority to every beat.

“Fer tambour la kozé!”

With her strong, carrying voice, Tasia has announced the opening signal across the gathering. Yes, the time has come to make the drums speak, they’ve been heated over the straw fire to tonal perfection. The drummers form a half-circle, the first hand rises, then falls to the stretched ray hide in five quick, measured beats. A brief silence, the vibration extends in concentric circles until it meats another membrane, invisible, under the belly’s skin. Then, the beats unfurl in synchronized momentum, a cavalcade erupting into a gallop, the beating inhabits the space, syncopates the blood’s pulse, lifts a primordial wave from the most profound depths of the body. The drums, suddenly, silence. Charlesia’s voice, made of cinder and salt, launches from her throat into peaks, soars then dissolves over the heads of the other participants.

Bat ou tambour, Nézim bat ou tambour

Beat your tambour, Nézim beat your drum

Ah Nézim bat ou tambour

Ah Nézim beat your drum

Nézim dime Wiyem alééééé…

Tomorrow to Wiyem, Nézim you’ll go-go-gooo

Tann mo la mor pa bizin ki to sagrin

Hearing Death’s words you’ve no more need for sadness

Pa bizin ki to ploré

No more need for tears

To a met enn dey pou mo tambour

O Nézim, my tambour mourns you

Tonight they’re taking up this song again, composed just weeks ago, for one of their best drummers, dead from old age. Wiyem didn’t want tears or sorrow. But he made them promise to render homage to his drum, his life. All throughout the vigil, between games of cards and dominos, they discussed. A little melody, a few lyrics were hummed. But they needed to until the days of mourning concluded. And now, tonight, they were keeping their word. They sing, they sing for Wiyem, they sing for his drum, for their drums seizing the limbs of an irrepressible vibration.

The women approach. Their feet landing flat on the earth, in one jolting movement their backs curve in a liberation of movement and trembling. The voices respond. The cadence accelerates. The infinite layers of ruffled skirts begin to swirl, sweeping the ground in great arches of movement, then hands catch the hems to lift them to reveal swaths of white petticoats covering their legs right down to the ankles.

The melodies overlap and transform in the yard, where the light of oil lamps dance in the night. The musicians take turns reheating their drums when they start to soften again. It is out of the question to interrupt the rhythm, or to let the atmosphere descend. Tasia doesn’t need to be asked twice for draughts of her famous kalou, concocted from a mix of lentil and corn mash set in a gunnysack to ferment, with a little sugar added from time to time. It’s even stronger than baka.

The hours disappear. The sky starts to pale above the sea. The men let the fire die into a quiet sizzle. One last dance, then it’s time to return, all together, to converge at one point, where they will join the next assembly preparing for tomorrow evening at Amelia’s, on the other side of the island.

“Alé nou alé, nou gété ki sannla inn fer pli zoli fet!”

In the middle of fits of laughter and teasing, the troupe strolls together to the beat of their drums. Yes, no self-respecting Saturday ends without a friendly squabble to determine where the most fun was had. Soon the sounds of other drums will reach them, accompanied by a stream of voices asserting victory.

Heavy eyelids squint against sun. The two groups squabble, each claiming superiority over the other. They review the details of their evening’s finest exploits, each insisting that their group pulverized the record of history’s most glorious ambiance-setting.

The only way to settle the debate is to organize one last, ultimate dance, right then and there, with the sun as final judge. Surrounded by shouts and applause the final showdown begins. The adversary-drummers measure each other up, provoke, combat, heckle, retort, then rhythmically unite in a last conflagration that sends the dancers into a frenetic whirl, until finally throwing them into the sand, breathless, straining with laughter.

Little by little, they collect themselves from the ground and go their separate ways, each to his own hut. They have just enough time to change their clothes and rush to mass in the little church, where the administrator officiates at the pulpit, between brief visits from priests en route to more sophisticated ceremonies and places.

Charlesia hastily splashes water on her face. The children had all returned home yesterday night, as they began to feel sleepy, and now they were beginning to wake. But what is Serge doing? He certainly knows that he needs to get to the spigot before the children, or else they’ll never be ready in time.

“Serge, kot to été?”

Charlesia calls out to him once, twice, and gets no response. He must be in the deep sleep that so often comes over him after the séga.

“Serge?”

Charlesia enters the hut. Hunched over the edge of the bed, his face flushed, Serge contorts in pain, gripping his right side.

Translator’s Note

To introduce The Silence of Chagos to readers is to introduce a complex political landscape in which whole populations become pawns, and whole islands become subject to seizure in the name of military prowess. The Chagos islands are an archipelago, a series of four larger and smaller curling islands which consist of a total land sum of 21.7 square miles some 1,200 miles South of the coast of India, and—until the years cited above—was home to the Chagossians. The Silence of Chagos is Shenaz Patel’s polyphonic fiction of reportage, inspired by a series of interviews she conducted with the people of Chagos she encountered as a journalist. Shenaz works to un-silence the Chagossian story, weaving together the voices of the people subject to forced exile between 1967 and 1973 from their native Chagos islands, an exile unceremoniously enacted by the British government, which resulted in the essential ‘sale’ of the islands to the US for the development of a strategic military base, currently active.

I first met Shenaz Patel at the International Writers Program in 2015. She stood among a room full of writers and students, and introduced us to the project of her work. Her voice was full of an urgency that I would soon discover also flooded and propelled her text, Le silence des Chagos. It is more than a novel, it pours light into a dark shadow of our collective recent history: the forced exile of an entire population from their native island to squalid shanties in Mauritius, where they and their children remain as the political world tries to do what is most convenient– forget. I hesitate here to categorize it as a novel of fiction, or documentary account, since throughout our conversations about writing, Shenaz actively resisted categorizing—labeling and thus limiting or restricting—what she harnesses in words.

Patricia Hartland graduated from Hampshire College with a BA in Comparative Literature and Poetry, and is currently a candidate for the MFA in Literary Translation at the University of Iowa. She translates from French with a special interest in Caribbean and creole literatures. Her translations are forthcoming with Two Lines and have appeared in Asymptote, Circumference Magazine, Ezra and Metamorphoses.

Shenaz Patel was born and lives in Mauritius. Journalist and writer, she has published four novels, numerous short stories in French and Mauritian Creole, four children’s books, two plays and two graphic novels.

She likes to define herself as an explorer. “Try to approach our secret humanity, dig deeper into things and people’s lives, with the broken but stubborn nails of words” : this is what she pursues through her writings. Attached as much to the inferiority of the individual as to the way they relate to a particular social organisation. Nurturing the voluntary utopia that writing could change the world…