Sad Nights of the North

In the North it’s night all the time.

No day is day,

and no night is night.

The sun’s cloak tore the river’s water,

a statue that hides its laugh

with mounds of hair.

The cries of the weepers rose

and the dead are an audience.

People dress in black,

but the day is not for mourning,

neither is the month

nor year.

In the North

there is a river of eyes,

locks of burnt grass,

and the water is red.

A flute, sword, and gun,

sword and gun,

a shy moon

frightened like a victim.

Panic is the god of the North

and fear is a god too.

No one knows anything—

everyone, even God, is misguided.

What’s to happen will happen—

blood, river, time, and death—

so says the prophecy.

Whenever chaos breaks out in the South

war breaks out in the North.

Language is lost there—

the pen sword,

not the sword pen.

Writing in the North does not follow any direction,

not upward

or downward,

right

or left,

printed

or cursive,

flowing on the line

or below.

Poetry cries out in the North.

And God

has lost his way.

Coda

The blood on the road

does not evaporate.

The plants don’t know

the difference between

them and water,

don’t know the color of the horizon.

Storm

It’s as if God has decided

to be in our village as water!

For two days, God kept raining,

flooding us with himself

until the channels overflowed,

rooms flooded,

people imprisoned in their homes.

We missed the birds, the squirrels, and the children.

Thank you,

Lord Master.

We get the message.

Come Sunday morning, we’ll be in church.

We won’t miss your hour,

Lord God.

Translator’s Note:

I’m delighted to see that publications are picking up on Saadi Youssef’s work and that his poetry is drawing perhaps even more interest now than it did when I began translating him more than three decades ago.

I can’t recall exactly when I first heard of Saadi. I left Libya as a teenager and did not start writing until late in a meandering undergraduate career. It wasn’t until I began walking the Borgesian book stacks of Indiana University’s graduate library that I began to read Arabic literature again. If my memory serves me right, it was in a year that I spent in Cairo, midway through my MFA, that I first saw Saadi Youssef’s name in print. But why did I recognize it as the familiar name of a poet?

Perhaps Saadi too would have been surprised that I, a prodigal removed from his language, would discover him. When Saadi left Iraq in the mid-sixties to take up teaching in newly independent Algeria, as an Arabic language teacher, he was walking away after a stint in prison for being a member of the Communist Party of Iraq. A decade before that he’d escaped the secret police of the Iraqi monarchy to Kuwait. In Algeria, he began sending his poems to the great journals and magazines of Beirut. In the first instance he was anthologized, he was included in a volume on poetry from Algeria, where no one knew he was even a poet. But word was getting around that there was a poet named Saadi Youssef, embraced by no regime or movement, although his political sympathies were clear. Saadi’s name traveled in almost the same manner that he read his poems out loud: quietly, forcing readers to lean in closer to the verse, whether they heard it in person or holding his books in their hands. Back in the U.S., I needed the quiet of a grand library to hear his verse, and voice it out in English.

Saadi’s descriptive, and unassuming, style was uncommon when he started out. His poems drew on his life in the marshlands of southern Iraq, an Edenic setting of water and greenery with great movable houses, and even mosques, made out of reeds. His poverty as a child oriented his sympathies, and his travels from a semi-primordial setting to the world’s capitals made him a nimble soul who could make a home anywhere, knowing that exile is not a political wound but the poet’s stance in the world, a gift not a curse.

A keen observer of the world, Saadi can best be imagined with pen and paper looking through a window and taking down what he sees. As in all great poetry, the extroverted eye is almost always seeking metaphors for what remains muddled and muted inside. So intimate was his verse, his readers in the Arab world never shouted his name out loud. Yet his name has been an open secret, or an open sesame, to a remarkable poetic sensibility that has powerfully widened the breadth of the region’s poetry.

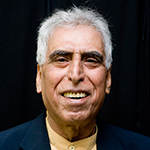

Saadi Youssef (1934-2021) is considered one of the most important contemporary poets in the Arab world. He was born near Basra, Iraq. Following his experience as a political prisoner in Iraq, he spent most of his life in exile, working as a teacher and literary journalist throughout North Africa and the Middle East. He is the author of over forty books of poetry. Youssef has also published two novels and a book of short stories, and several books of essay and memoir. Youssef, who spent the last two decades of his life in London, was a leading translator to Arabic of works by Walt Whitman, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and Federico Garcia Lorca, among many others.

Khaled Mattawa is the William Wilhartz Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan. Mattawa’s latest book of poems is Fugitive Atlas (Graywolf, 2020). He is the editor-in-chief of Michigan Quarterly Review.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE