A Checklist for Dark S(Kin) Care

“To be truly visionary we have to root our imagination in our concrete reality while simultaneously imagining possibilities beyond that reality.” -bell hooks

What is the right shade of brown in America?

Western med school students have been and are currently still trained to diagnose skin conditions by studying photos of mostly white bodies. They admit that almost “…half of US board-licensed dermatologists don’t feel comfortable diagnosing skin issues in people of color” because they don’t know how to look at darker skin. What’s worse, the few black bodies photographed in textbooks show only sexually transmitted infections. The images are “reminiscent of slave auctions, looking at their muscles and reproductive potential, humiliating them.”¹

There’s an old-ass Flexner Report that led to this literal, racist whitewashing—by shutting down Black medical colleges and other med schools that taught Native American healing along with, “herbalism, homeopathy, and chiropractic,”² which were legit modalities at the turn of the 20th century.

And what if that shady brown girl’s skin is sick? What if she’s a walking band-aid, a perpetual affliction?

One in four Americans have skin diseases, costing $75 billion a year to treat. Throughout my decades of inherited dis-ease, I’ve invested in doctors after healers after elimination diets after practitioners after stress-eating all the potato chips after therapists for help, to cure the seemingly incurable skin.

An acceptable shade of brown. Is there such a thing?

For fellow brown n’ broken skin kin, here’s a list of what I’d want for us, an ideal dermatology visit. Lemme know what you’d add because I want this to be a radically collaborative exercise:

❑First of all, the reason you made an appointment is because on their website is the clinic’s Skins of Color Acknowledgement. They promptly recognize and commit to reparations from Western medicine’s racist, whitewashed historical and present practices. (You may arrive at the office a little SUS–as the kids say–and that’s okay. Our bodies are good at guarding us. Can you gulp water and exhale as you walk in? Text me; if you want, I can meet you there.)

❑The receptionist maintains eye contact, warm, genuine. They don’t wide-eye, gaze down or stare sideways at our skin.

❑They thoughtfully considered our skin history before we arrived. They offer us a prepared soothing drink made from safe-for-us plant medicines. For me, it’s coconut water, tamarind juice, bayabas (guava) leaf tea.

❑We are shown a buffet of lotions and ointments, and we are trusted to choose the exact ones that work (for now—this is a rotating sitch based on weather, allergens, triggers).

❑Our treatment room is set to the climate best for our skin needs. For me, tropical climate: humid air, thickly fragrant with sweet banana leaves and Philippine jasmine, the sampaguita flower. (Big, frizzy hair is a default here!)

❑Instead of abstract art on the walls, there are photos of all ages and skin conditions reflecting us: rashy, brown, gap-toothed, freckled, peeling, black, wrinkled, rosy, plaqued, scarred, beloved.

❑With consent, we are touched gently “where it hurts,” not man-handled like a specimen or a thing with cooties. Here, they, “move at the speed of trust.” Whenever we want, and for as long as it feels good, we are hugged.

❑We rest on a warm amethyst bed, and acupuncture needles are applied to move, to release stuck or unstimulated chi—some ancestral energies waiting to be unblocked. If we need the sun’s healing (without the damaging UV) we glow underneath light therapy panels while our weary chi flickers, flutters and flows.

❑Upon our request, at any time, we can listen to audio of prose potions (e.g. Ross Gay’s Book of Delights, Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals.)

❑If further narrative medicine is needed, the doctor meets us outside where we prefer (beach, park, our neighborhood) for a long walk to hear more of our story. They witness our wonderings about why our skin is inflamed and erupting. They say, I’m sorry you’re hurting. They ask often, too, What delights you? They teach their staff to do the same, to say, Tell me more.

❑This could be when the doctor shares stories of their own family’s experiences with skin dis-eases. It’s precisely because their own flesh and blood suffer that they chose to become a dermatologist.

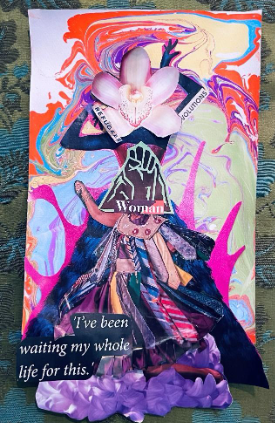

❑We make art, like kids who parallel play, as we ruminate and celebrate the latest therapies and treatments in communities around the planet. (A favorite: cutting and gluing collage³ visions.)

❑The more we come for treatment and care, we realize others are hanging out in this Third Space. They choose to be here. We get it; we get each other—breached skin and all. It’s deep listening without “advice” and “should-ing” on ourselves. It’s hell yeah when one has a good night’s sleep or is in remission. As regular practice, we tend to our griefs. Heart medicine.

❑For those curious and open to a little spirit-trippin’, we recline in a bed lined with fresh aloe. Indigenous healers circle us, massage coconut oil into open wounds and sing over us. We are bathed in ancestral tongues. Their voices ribbon throughout the center, weaving everyone together in song.

❑After each visit, on our way out, we are given baskets to fill with orange food our bodies can enjoy. Real orange food (not Cheetos orange) offer skin-supporting nutrients. The staff and allies grow, prepare, and bring carrots, pumpkin muffins, sweet potato chips, roasted butternut squash, dried apricots, mango smoothies, wild yam soup.

❑There are more lotion and ointment travel sizes to take, to dole out. Lotion as love language. A sign invites, “Grab and give to other skin kin!”

❑The one thing that does not fill our hands, pockets, and baskets? A bill or co-pay.

❑When we’re ready for our next appointment, the day and time we prefer is open and waiting.

Yes, I know, this sounds BOTH so reasonable and yet, as our experiences with the medical system remind us, too good to be true. I promise, it’s possible. I’ve experienced many of these treatments. Join your dreams to ours, so we can dream the rest into life.

May we read these out loud, first to ourselves, then around a table or fire. May we yell them into the ocean, bury, drown, spit and scratch, dig ‘em up.

May we print this out to bring to our next appointment.

May we offer to the doctor, nurse, receptionist, therapists and techs. Our neighbors and frenemies, too. Like a birthing plan that includes the whole community.

May we raise our hands and say, This is what we want and need. We’ve been waiting our whole lives for this. Believe us. We are laboring together, our

earth-cracked

skins en-flamed,

dancing and dripping.

¹ From Inflamed: Deep medicine and the Anatomy of Injustice, Rupa Marya and Raj Patel.

² ibid.

³ Collage is traced to China in 200 BC… “today, art involving pieces of paper, photographs, fabric and other ephemera arranged and stuck down onto a supporting surface.”

Ephemera, “lasting only a short while.” See, “life.”

Supporting surface, see: Collective Care

Ella deCastro Baron is a second generation Filipina American teacher and storyteller, a VONA alum, and cohort leader of Corporeal Writing’s 2024 Mushroom School. Ella’s first book, Itchy Brown Girl Seeks Employment, is an ironic curriculum vitae of her ethnic upbringing, inherited faith, and chronic illness. Her forthcoming book, Subo and Baon: a Memoir in Bites, is a ‘meal’ that offers nourishment while decolonizing harmful systems, so we can “re-member our long body,” recover fuller stories and indigenous ways. Ella cultivates kapwa (Filipino value of deep interconnection, shared identity) in communities near and far. Her favorite pronoun is We. elladecastrobaron.com.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE