The Fisherman’s Wife Has Something to Say

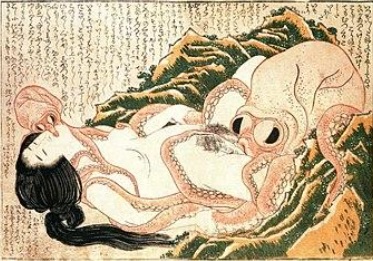

after Hokusai, “The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife” (1814)

First of all, I’m not a fisherman’s wife, so stop calling me that. I’m not even married.

Second, it wasn’t a dream. But I’ll get to that in a minute.

Hokusai-san didn’t name his image, but we call it “Tako to ama.”

Tako: octopus. Or octopuses, octopi—take your pick. We are less hung up on distinguishing between one and more than one of something.

Ama: diver. For thousands of years, we’ve dived, my mother and grandmothers and their mothers and grandmothers. On a good day, we return with buckets lined with oysters and abalone and sea cucumber, enough to exchange for rice and wine, maybe fabric, a packet of needles. On less good days, which happens more often as the world and its oceans grow tired, we return with only enough to feed ourselves.

What we really want, of course, are pearls.

That’s the dream: to steam or force open an oyster and find, resting on that quivering muscular bed, one—or more than one!—lustrous, nacreous, valuable sphere.

Today the women who dive for the entertainment of tourists wear modest white uniforms. In my day, we wore just headscarves and loincloths. Both of which I seem to have lost during this encounter. Tch tch.

Anyway, there’s nothing about marriage or fishermen. That’s some Western invention. Art “critics” who couldn’t read the text assumed the picture depicted a rape. Some even surmised that the two cephalopods were messing with a drowned woman. Then called it “The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife.” I mean—what?

And like I said: It wasn’t a dream.

One morning, I swam away from my mother and aunts toward an oyster bed they forbade me from visiting because, they said, it was guarded by a giant octopus. And they were right. I’d collected ten lovely, promising specimens when suddenly the octopus was before me, crimson with fury, tentacles flaring. I launched myself up and away, only to surface on a roiling gray sea, quite alone, no sign of our boat or the other women. A squall had blown through while I was underwater. Even my bamboo bucket was gone.

Everyone assumes the octopus was male. Even Hokusai-san. He thought the smaller creature, the one that’s kissing me, was its son—which, you know, is a little weird. I think it might have been a different kind of mollusk altogether. Or they might have been a pair, these two, but not father and son. A mating pair, the smaller male and outsized female, exhibiting the remarkable sexual size dimorphism some species are known for—and perhaps a desire to spice up an old partnership?

I wasn’t thinking about any of this at the time, of course.

I had been treading water, hopelessly scanning the horizon, when the giant octopus appeared beside me and curled a tentacle around my hands. I surrendered my oysters and expected to die. But the creature pushed me gently toward shore, supporting me with its many arms when I grew tired, and helped me up onto a rocky beach, soft and slick with sea grass. As I lay there catching my breath, amazed to be alive, the octopus pried open my oysters one by one and slurped down the meat, sharing a few with its wingman. But first it held out each breached bivalve for me to see, as if showing me there were no pearls inside for me to regret.

Hokusai-san was a marvelous artist, but a bad erotica writer. He scrawled all this noisy, silly dialogue around us. I’m not going to translate for you, but—here, just listen: the octopus says, Are are, naka ga fukure agatte, yu no yō na ai-eki, nura nura doku doku, and I supposedly go, Korya dō suru no da… yō yō are are ii ii, mō mō dōshite, ee, zu zu zu…

Zu zu zu? Come on, Hokusai-san. Who sounds like that in a moment of esctasy? We’re supposed to be masters of onomatopoeia.

It’s all right. The artist can’t know everything. Here’s something else he didn’t know: How the octopus reached up inside me until I thought I might break open, then withdrew its miraculous tentacle, shooed the little guy away from my mouth, teased open my lips, and dropped a large, perfect pearl between my teeth. It tasted of the sea, it tasted of desire, and I could have sold it and lived in comfort the rest of my life. But I didn’t. I kept diving, and I kept the pearl, a reminder that the finer treasures lie within, and the finest lovers know how to bring out the best in you.

Naomi Williams is the author of Landfalls (FSG 2015), long-listed for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in numerous publications, including One Story, Electric Literature, Zoetrope All-Story, The Rumpus, and LitHub. A five-time Pushcart nominee and one-time winner, Naomi has also been the recipient of residencies at Hedgebrook, Djerassi, Willapa Bay AiR, and VCCA. A biracial Japanese-American, she was born in Japan and spoke only Japanese until she was six years old. Today, she lives in Sacramento, California, and teaches with the low-residency MFA program at Ashland University.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE