Bearded Mouth

In primary school, I had this teacher. I don’t remember her name but if you ask me to close my eyes and think of her, I’d see three things: One, a beautiful pastel green pencil skirt she would often wear. Two, a ripe black mole by her upper lip. And three, a dark-skinned chin, full of even darker hair. Well, maybe not “full of hair”, but just enough coarse-looking coils to stir us into calling her a wicked witch when she wasn’t listening. “Ah, she can eat you oh!”, “She is wicked to her husband”, “Don’t you know she hates children?” “She will flog you 60 times!”—these were the mythical lies that 9-year-old children were throwing across the P.6 classrooms like a game of telephone. In retrospect, the source of these accusations was never verifiable. I was either hearing it from one loud-mouthed boy who ate his cold lunch with too much saliva in his mouth, or I was hearing it from another boy who would elaborately plan to push my pencil case down during end-of-term party so I would bend and he would see under my skirt. Imagine. Meanwhile, I don’t think she beat any of us more than any other regular Nigerian cane-loving enthusiast. In fact, I don’t think that woman had ever touched me with a cane in all the years I went there.

Then why was I so quick to believe those stories?

Honestly, as pathetic as it may seem now, I really thought boys knew more than girls at that age. I learned somewhere that the loudest voice was carrying the strongest reasoning. But more gravely, somewhere in the recesses of my 9-year-old mind, I was very comfortable believing that women who had facial hair were unkind, treacherous, monstrous, capable of great unkindness and quite frankly, willing to devour children they wanted to punish. A few years ago, I got lost on the World Wide Web and found myself in a Nairaland forum where a man spent some hundred words, complaining bitterly about all the hair his sister had on her chest. By the end of the post, he had called his sister Satan without ever mentioning any evil she had done. The conclusion was made on the single premise that she had a hairy chest. And there it made sense, why my mother’s mood always seemed to deflate on the days when I would see a tiny hair on her chin, and move to stroke it.

In 1957, a Spanish physician —Juan Huarte— decided that “the woman who has much body and facial hair (being of a more hot and dry nature) is also intelligent but disagreeable and argumentative, muscular, ugly, has a deep voice and frequent infertility problems.” Reasoning like this has lasted until now. Growing up and hearing similar myths about women with facial hair led me to regard facial hair on women as an abnormality that hit maybe 1% of the population. However in her article, Female facial hair: if so many women have it, why are we so deeply ashamed?, Mona Chalabi reports that as many as 1 in 14 women deal with the growth of male-patterned hair from as young as 11 years old. 1 in 14 women makes a total of 56 million women. 56 million is a lot of women made to think they are terribly unusual; a huge chunk of women made to feel inherently criminal, based on nothing they have done by the work of their hands or intention in their hearts, but merely by the hair on their chinny-chin-chins. It is a crazy, yet popular, opinion that women with facial hair are criminal. In her work, Chalabi also recounts the influence of Darwin’s book, The Descent of Man, on male scientists hungry to validate an obsession to segregate by using racial hair types to indicate primitiveness. “One study, published in 1893, looked for insanity in 271 white women and found that women who were insane were more likely to have facial hair, resembling those of the ‘inferior races,’” she reports. Fortunately, this wasn’t always the truth everywhere. While Darwin and Huarte where working hard to segregate and negate women with facial hair, the Yoruba people down south were building the sacred image of a bearded female leader called “Iya Nla.”

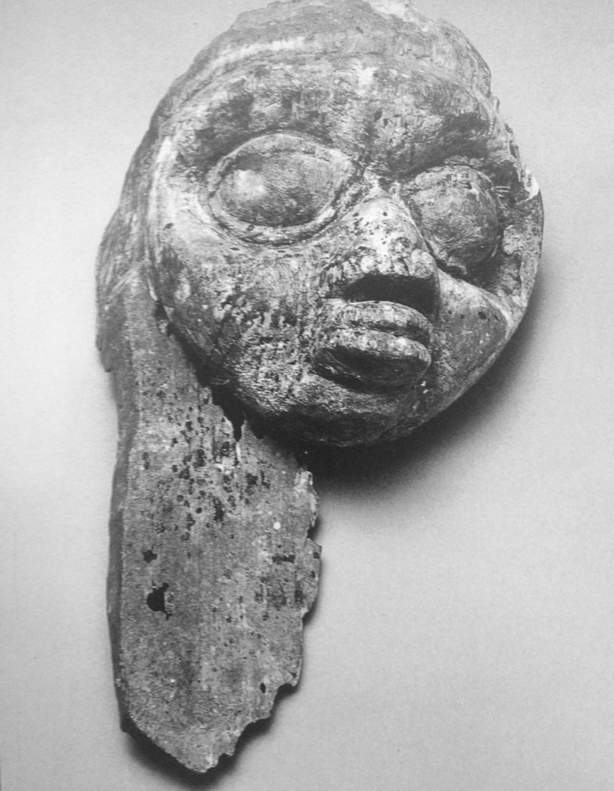

The Iya Nla face figure is the most sacred mask paraded during the annual Gelede festival, a procession of masks dedicated to perform and portray the tropes of femininity as accounted in Yoruba oriki. As opposed to the other masks, the Iya Nla is the only one carried at night, covered in an opaque veil that suggests an otherworldly power, too great to be seen, but so powerful it must be acknowledged. For scholars like Henry Drewal, the Iya Nla face represents “the essence of Gelede, and constitutes the foundation of Yoruba society.”

“The word Gelede describes a spectacle that relaxes and pacifies the beholder,” writes Babatunde Lawal, who has written most extensively on the subject. In his words, Gelede is primarily dedicated to the maternal principle in nature, personified as Iya Nla, the Great Mother. There are many different origin stories of the festival, most of which conclude that the inner spirit of the sacred mother must be evoked for any fertility and reproduction to occur. What I find interesting here is that in a festival designed to conjure up the most cultural epitome of femininity—childbirth—the most important visual metaphor of that the event is that of a woman with a bearded face. Meanwhile, in our colloquial understanding, the beard seems to negate that femininity, and seemingly cause sterility. But even though the beard (irungbon), in Yoruba culture, is seen as a symbol of wisdom and advanced age, women with one are very cautious about keeping it, for fear that they may be accused of being Aje (commonly translated as “witch”).

How manage?

Well, it turns out that fear is partly responsible for this misunderstanding. By creating myths of woman as an inherently secret creature who would attack you without your knowledge, there is a paranoia that women aim to be feared, rather than understood. Apparently, there have always been rumours of women who would “just look at you and that will be the end,” or the women who could steal your organ by walking past you. The myth of the irascible and wicked Aje has unfairly allowed women to be punished arbitrarily, for making gestures that may correlate with, but not cause, misfortunes. As a result, women have had to take extra caution to rid themselves of anything that may seem Aje-like.

But before being negated to mean witch, “Aje” was a word for the respected mothers who could be destructive, but more often, brought balance and maintained social order and morality (Ifogbontwaase). Because the mechanism of their healing wasn’t articulated visibly in the same way as masculinity, the feminine power was often embedded in mystery. The fear of the unknown provided a competitive threat to the predictable and visible strategy of male physical power paraded in battles and exposed through war. In his book, The Gelede Spectacle, Lawal explains that “to the Yoruba, nature has compensated the women in other ways by giving them cunning (ogbon aje) with which to level up with the physical advantage of men.” And so, men cannot allow themselves to be manipulated by the “…explosive nature of male-female relations in a male dominated society.” When Henry Drewal, author of the book “Gelede”, interviewed some local Yoruba men, he also confirmed that there was a reverence for women’s power that bordered on revulsion and fright. One of the men complained that women have the power to bring technological advancement but instead choose not to:

“[T]he aje change into birds and fly at night. If they used that knowledge for good, it might result in the manufacture of airplanes…they can see the intestines of someone without slaughtering him; they can see a child in the womb. If they used their powers for good they would be good maternity doctors.”

In his mind’s eye, women are responsible for holding back their creative strength. On one hand, the thought seems empowering. But on the other hand, it dismisses the systemic dilution of femininity into only things that smell like candy, and bodies that glisten hairlessly in the sun. While some women do prefer to smell like candy or glisten hairlessly, it is important to see the ways others make the world unlivable for women who refuse to participate in the performance of that one fickle, and pre-colonially dislocated narrative around femininity. The truth is that some women with beards will wax for the rest of their lives. But some women won’t. Unfortunately, some of the women who don’t will get death threats from men, insisting that it is morally wrong for them to retain the hair on their faces. Women like Harnaam Kaur: a 29-year-old woman who decided to stop shaving frantically every morning. Without caring that Kaur has polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) which can offset hormonal changes and increase hair growth, causing both emotional and physical pain, there are strangers on the internet that threaten to take her life away if she doesn’t shave. It is not hard for me to imagine that the Nairaland guy threatens to do the same to his sister for harbouring hair he deems Satanic.

With more time, I could guide you into the profound world of scientific and biological reasons why women grow male-patterned hair on their bodies. However, this is not that essay. This is a shorter one that simply asks that we see how far our realised forms of femininity have deviated from what was once the mystical, idealised metaphor of a full femininity that placated the earth and removed hostility from its womb, providing abundance and regeneration for all who asked. If the face of that prayer is that of a bearded woman, why and how have we become so ungrateful for what the bearded women in our lives can teach us about duality and harmony?

“Iyamapo toto aro no dama e ko kere abirun lenu”

Iyamapo, please, I beseech you, I do not intend to slight you with bearded mouth

-iwi Egungun (translated by Theresa N Washington in The Architects of Existence: Aje in Yoruba Cosmology, Ontology, and Orature)

In this moment, I wish I could reach out to my old teacher and tell her we were just silly. I wish I could tell her I didn’t know her well enough to make any of the judgements I made. I wish I could tell her she never has to agree with the loudest opinion; that in matters of wisdom, might definitely doesn’t make right. If you could take me back to Primary 6 with what I know now, I would un-look that over-salivated young man along with his foul-mouthed accomplices, and find a way to let her see that, according to Yoruba mythology, a bearded woman may, in fact, be the sacred reason for every season.

Sheila Chukwulozie is a filmmaker and tea-maker who uses the camera to preserve the full range of human expression in the belief that emotions like civilizations, may one day go extinct. Her works have been shown in, Nigeria, Ghana, Cote d’ivoire, England, Germany, South Africa, Czech Republic and USA. In 2020, Sheila spent three months with Delfina Foundation filming a documentary film on the relationship between pole dancing and religion called |temple| of which an excerpt has been shown both in Delfina foundation and Arebyte gallery, London. From August 2017- August 2018, she travelled as a Thomas J Watson fellow studying with traditional mask makers and cloth weavers in eight African countries. As a writer, she writes mainly on the African perspectives of global matters relating to sonic history, anthropology and digital humanities. Her work has been published by The Republic Journal, Disegno and Infrasonica. Her latest essay published by LIFE magazine was long listed for the SOPA journalist awards 2022. Her installation at the Johannesburg Art Fair “Thanks Xenophobia” has been reviewed by Artnet, Frieze, Financial Times and other leading media houses. Her latest film “Egungun” (directed by Olive Nwosu) has been launched at the British Film Institute, TIFF International film festival, Aspen film festival and Sundance. Her most recent installation called “OBSIDIAN” is a collage of materials—visual and audio—made in collaboration with artist Jasmin Fire, curated by Raphael Guilbert. The piece showed through a digital portal connecting Berlin to Lagos in real time, using live feedback from both performers and audience members.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE