This My Country No Longer My Country

—an elegy for the martyred Egyptian immigrants who drowned on the coasts of Italy, Turkey, and Greece

All my life I have wondered: where is the face of my country? Where are

the palm trees, the warmth of the valley?

In the horizon only darkness, and the headsman’s image: it never fades

away.

It is part of our fate, between birth and resurrection.

I live in the call that raises palaces from gray hills.

I long for my beloved land’s honor of both will and drive.

I long for children dancing like drops of dew in morning.

I long for days whose magic has faded, the bustle of horses, the joy of

feasts.

I miss my old country.

We moved, and it moved.

In every bright star, an orphaned dream.

Every cloud a gown of grief.

In the horizon, flocks of leaving birds forego singing, become a swarm of

locusts.

This country traded in its land, fragments of the whole, subdivided for the

auction.

All that remains of the hustle of horses is sorrow.

Our history is full of glistening horses, but now I only see the headsman

raping the valley, and a gang that twirls the blood from our eyes.

The day’s cries subside, and the tombs are heavy with ancestors.

There is no light from a wandering star.

No longer a release dove’s coo.

Sadness cackles past us, drops by without an appointment.

Something has broken in my eyes.

The times are fed up with the revolution I loved to the edge of madness.

When beauty is pimped, even the morning gets beaten.

The land is devoured by the fire of slavery.

Don’t ask me about my country’s tears during martyrdom, when agony

hunts every acre.

In the pale distance, beyond the black mountains, I see black mountains.

I see waves breaking over our heads, feel gravel grit my skin in the wind,

as the horizon’s line is washed out.

I raise my frostbitten hands to flag down a passerby, and see it is my

mother dressed in black.

We embrace, as if saying goodbye, and the sea heaves on with its corpses.

Up until the moment of death, I will still rise with a bright heart, knowing

this is my daughter’s face carved on my chest.

Farewell, mother—a sack of salt is all our food.

Give my shirt back to my mother, she saw what I couldn’t see: the string

between destiny and death, a hijacked homeland that threw me

away.

I see from behind the borders a parade of the hungry chanting for their

masters’ protection, and death-crowds cheering around the hungry.

In the middle of this weeping life, seized in the call of longing, the times

passed me by.

Remember the story of a hopeful lover who left his home for the promise

of another country?

It turns out that country had nothing to offer, could only bow to the pimp.

My pulse is heavy, and all will be silent soon.

The mirror of birth and death is glass-dust, and in its grains I see the

headsman and his gang.

And I see the river, and I see the valley, and I open my mouth for silence,

for a country that is no more.

Forgetting

I carried all I had through the tangled night, blaming the road

that spurred me backward to green windows, witness

to the hunger of our bodies, witness to the underside

of forever. Alone now in the road’s slow night,

I re-sense the first days’ blush, the flash

of your hand in mine: how do you bear all that is past?

Such bluff inside my boast: I will forget you.

I try to move on, but a shadow slides along, chiding that folly.

Beside the road, pale light seeps into yellow tulips,

and I quicken for what is lost: youth, freedom, dreams.

Aimless, I stare at the ground until dizziness takes me.

Somewhere in the dust of these empty streets where we began:

the warmth of our hands. Somewhere in this dust

our savoring footsteps, somewhere my roving tears.

Like the endless road, my story is here and there at once.

Can I resist the was that beckons? Shall I continue alone?

As your memory strums the chord in my chest,

the threads of my journey unravel, unravel.

Who Said Oil Is Worth More Than Blood?

As long as we are ruled by madness, hounds

will devour fetuses still in their wombs,

mines will sprout in wheat fields, and even

the crossed light of morning will be eye-fire.

We’ll see the young hanged, wronged

at the dawn prayer. It’s an age witness

to a snarling pig fouling mosques.

When madness rules, there are white flowers

on the ruined branches, emptiness

in a child’s eyes, no kindness, no faith, no

dignity held sacred. All fates futureless,

everything present worthless. As long as madness

rules, the children of Baghdad can only guess

why they wander hunger’s thorns,

why they share the bread of death, why off

in the distance, American Indians

hover in the cold, why greed shouts them down,

every race crawling ghost-hearted.

Through blood-colored streets, between humiliation

and disbelief, crippled shadows creep,

and the madness-hounds howl in our minds.

We are on our way to death.

***

The children of Baghdad scream in the streets

as Hulagu’s army pounds the city’s doors

like an epidemic; his grandchildren roar

over the bodies of our young.

The wings of wild birds are blood rivers,

black claws claw eyes—all this cracks the silence.

The Tigris River remembers those days, so look

behind the curtain of history—how many

aggressors have passed through the centuries

of our land, and still we resist?

Hulagu will die, and the Iraqi children

will dance in front of Degla. We are not

to be hanged from all corners of Baghdad.

***

A river can be a weapon against injustice on the earth.

A palm can be a weapon against injustice.

A garden can be a weapon.

Among the water, in the silence

of tunnels, though we hate death,

for God and right we will set fire forever

to your refusal that Islam is holy.

Baghdad, raped by tyranny, your children

are raising flags. Where are the Arabs

and the white swords, wild horses, glorious families?

Some of them were condemned, some

fled shameful, some stripped and gave away

their clothes, and some are lined up in the devil’s hall

to get their share of the spoils.

And people ask about a great nation’s ruins,

but nothing remains of that shining empire

that spans from the ocean to the gulf.

***

Every calamity has its cause.

They sold the horses and traded in

the knights in the market of rhetoric:

Down with history! Long live hot air!

Death comes to the children of Baghdad

in the smallest toys, in the parks, in restaurants,

in the dust. Walls collapse on the procession of history,

shame upon civilization, shame from a thousand borders.

From the unknown, a missile charges,

“Where are the weapons of mass destruction?”

Will daylight come again after the virgin smile

has been erased, after planes block the sunrays,

and our dreams spurt suicidal blood?

By what law do you demolish our homes,

and flood fire upon a thousand minarets?

In Baghdad, days pass, from hunger to hunger,

thirst to thirst, under the gaze of the master

of the mansion, the thousand-masked face.

Will there never be an end to this nonsense?

The curtain rises: we are the beginning.

To starve people—is this honor?

“To prey upon supplicants”—that’s the glorious slogan of victory?

To chase children from one house to another—the joy of tyranny.

These days, people have the right to humiliation, submission,

death in every atom, and the chronic question,

“Where are the weapons of mass destruction?”

***

The children of Baghdad are playing in schools:

a ball here, a ball there, a child here, a child there,

a pen here, a pen there, a mine here, a death there.

Among the fragments, the cactus.

There were children here yesterday,

fluttering like pigeons in open spaces.

One of these days, dawn might lighten the universe,

but for now the sun of justice is far below the horizon.

***

Despite sacrifice, there is a dark gluttony:

some are faithful, and some are sellouts.

Oh nation of Mohammad, my heart longs for Al Hussein.

Oh Baghdad, land of Caliph Rasheed,

oh castle of history, and once-glorious age,

the two moments between night and day are death and feast.

***

Among the martyrs’ fragments,

the throne of the universe, shaken by a young voice.

The dark night leaves when a new day flows.

Oh land of Al Rasheed, don’t lose hope, every tyranny ends:

a child adores Baghdad, holds a white notebook and flowers,

paper and poetry, some piasters from the last feast.

***

Behind his eyes, a tear that won’t break

but flows like light deep in his heart: the picture

of his father who left one day and never returned.

The child embraces ashes, and stays a long time.

A thread of blood runs through his mouth;

his voice and shed blood are one.

His features washed out; all of this world is separation.

The child whispers, I long for Baghdad’s day.

Who said oil is worth more than blood?

Don’t ache, Baghdad, don’t surrender.

Although there is dissent in this blind time,

there is, in the far horizon, a wave of visions.

Although the dream is distant, it rises. Rise,

and spread my bones in the Tigris River,

so daylight will one day rise over my funeral procession.

God is greater than the madness of death.

Who said oil is worth more than blood?

translator’s note:

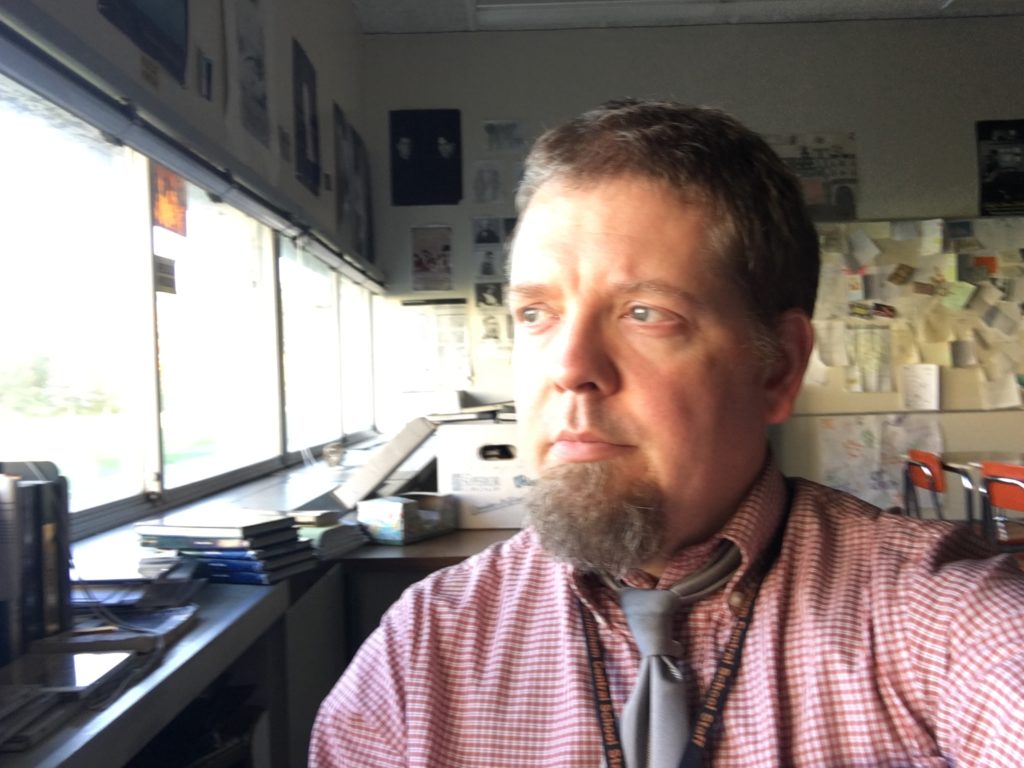

Walid and I are met as part of an international educational exchange program housed by the College of Saint Rose here in Albany NY, during which Walid regularly visited my high school classroom for about three months to observe, talk, and collaborate. After teaming a couple of lessons on political poetry from a variety of countries, we thought it would be fun to collaborate on some translations of contemporary Egyptian poetry, which has received relatively little attention here in the U.S. Walid was particularly drawn to the work of Farouk Goweda, who is a literary giant in the Middle East.

Because I do not speak, read, or write any Arabic, Walid is responsible for the most important step: the initial renderings of Goweda’s work into English. Parts of those initial translations need, in my view, very little or no editing or re-casting into poetic American English. I take the parts that do need reworking and edit for simple correctness, clarity, and suggestiveness. Sometimes I move lines around a bit out of their original order to emphasize certain images or progressions. I often follow up with Walid on questions about intent, clarity of meanings, allusions, historical figures, shifts in tone, and cultural symbols. I always send him final drafts for approval, and he has been in touch with Mr. Goweda, who is glad to see his work steadily and increasingly recognized in the United States.

Line and stanza breaks are the most consistent liberty I take (though I do take occasional ones with certain images or colloquialisms): I do not think any of the poems we’ve published actually follow Goweda’s original lineation or stanza structures. I have approached those features searching only for a combination of line and stanza that both contains and propels the rhythm, power, and image-laden lyricism of Goweda’s work. I am fond of either uniform or alternating stanza lengths, with a small range of syllables per line, but I have tried to let the content of the lines drive the shaping of the lines, so some poems have had small syllabic ranges, whereas others stretch and sprawl similar to those of Whitman or Ginsberg.

In terms of content, Goweda is especially well-known for his political, religious, and love poetry—sometimes, at certain moments in certain translations, we have allowed those lines to be blurred. Of the three included here, “Forgetting” is both love poem and lament on the passage of time, and “Who Said Oil…” is a response to American foreign policy in Iraq. “This My Country No Longer My Country” elegizes a story we find in more than one part of the world, but has occurred in Egypt since the 1980s: illegal immigrants fleeing corruption and poverty in their home countries in hopes of making a better life in Europe.

Farouk Goweda is a bestselling Egyptian poet, journalist, and playwright whose nearly 50 books have been widely influential in the Middle East for their technique and content. His work has been translated into English, French, Spanish, Chinese and Persian, and he has been awarded several national and international prizes.

Walid Abdallah is an Egyptian writer whose books include Shout of Silence, Escape to the Realm of Imagination, and Male Domination and Female Emancipation. He has been a visiting professor of English language and literature in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Germany and the United States. His co-translations with Andy Fogle of Farouk Goweda’s poetry have previously appeared in Image, RHINO, Reunion: Dallas Review, and Los Angeles Review.

Andy Fogle’s sixth chapbook of poetry, Elegies & Theories, is forthcoming from Presa Press. A variety of writing has appeared in Blackbird, Best New Poets 2018, Teachers & Writers Collaborative, English Journal, Gargoyle, and elsewhere. He lives in upstate NY, teaching high school and working on a PhD in Education.

BACK TO ISSUE

BACK TO ISSUE